July 28, 2019

by Steve Stofka

Did you know that housing costs double every twenty years? The predictability surprised me. Both rents and home prices double. Based on the last forty years of data the average annual increase is about 3-1/2% (Note #1).

House prices can only get ahead of earnings for so long before a correction occurs. Take a look at the chart below. Yes, low interest rates reduce mortgage payments so people can afford more home. That’s what we said in the 2000s. This trend does not look sustainable to me.

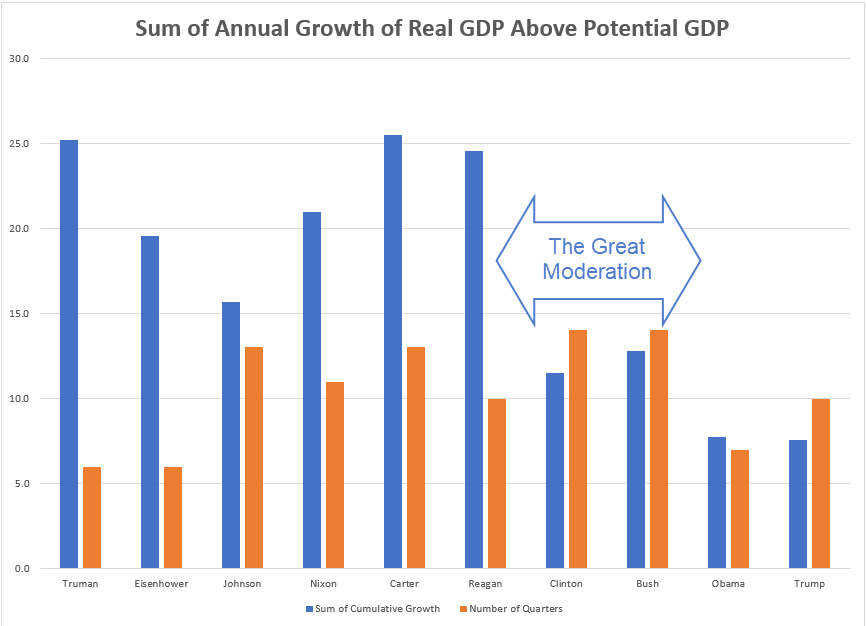

I was doing some work on potential GDP and wondered which president since World War 2 has enjoyed the longest and strongest run of real (inflation-adjusted) GDP above potential. Potential GDP is estimated as a nation’s output at full employment.

I won’t start with the #1 award because that would be no fun. Nixon came in fourth place with a run of strong economic growth from 1971 – 1973. The oil embargo that followed the Arab-Israeli War of 1973 sent this country into a hard tailspin that ended that growth spurt.

Ronald Reagan comes in third with a cumulative total of 24.5% growth above potential GDP. The expansion began in the third quarter of 1983 and ran through the second quarter of 1986. These strong growth periods seem to last two to three years.

Second place goes to President Truman with a short (less than two years), sharp 25.2% gain that ended with the beginning of the Korean War.

And the award goes to…the envelope please…Jimmy Carter. Wha!!? Yep, Jimmy Carter. The growth streak began in 1976, the year Carter was elected, and ended in 1979 when Iran overthrew their Shah, oil production sank, and oil prices doubled. At its end, the expansion had totaled 25.5% above potential GDP. In less than two years, the nation soured on Carter and put Reagan in office.

What about other Presidential administrations? We might remember the late 1990s as a heady time of skyrocketing stock prices during the second Clinton administration. The output above potential was only 11.5% but is the longest period of strong growth, lasting almost four years, from the first quarter of 1996 through the last quarter of 1999.

George Bush’s growth streak was only slightly higher at 12.8% but is the second longest growth period, beginning in the third quarter of 2003 and ending in the last quarter of 2006. A year later began the Great Recession that lasted more than 1-1/2 years.

Barack Obama’s presidency began with the nation deep in a financial crisis. By the time he took office fourteen months after the recession began, the economy had shed 5 million jobs, 3.6% of the employed. Employment was more than 6 million jobs below trend. The economy did not start growing above potential until the first quarter of 2010. The growth period ended in the third quarter of 2012, but employment did not regain its 2007 pre-recession level until May of 2014, 6-1/2 years after the recession began. It is the weakest strong growth period of the post-WW2 economy.

President Trump’s streak of strong growth began in the last few months of Obama’s term and is still ongoing with a cumulative gain of 7.5%. Unlike other growth periods, this one is marked by steadily accelerating growth above potential.

I’ve charted the cumulative growth above potential and the period length for each president.

As the economy shifted away from manufacturing in the 1980s, the days of 20-plus percent growth ended. Manufacturing is more cyclic than the whole economy. The manufacturing sector contributes to strong growth in recovery and pronounced weakness at the end of the business cycle each decade. In the 1980s, economists and policy makers in both government and the Federal Reserve welcomed this shift away from manufacturing. They dubbed it the Great Moderation and it ended twenty years later with the Great Recession.

President Trump is on a mission to begin another “Great” period – the resurgence of manufacturing in America. It is a monumental task because manufacturing depends on a supply chain that is presently located in Asia. In 2013, Apple tried to manufacture and assemble its high-end computer, the Mac Pro, in Texas. Production faltered on the availability of a tiny screw (Note #2). Six years later, the Trump administration is levying 25% tariffs on Apple products to encourage them to manufacture computers again in Texas.

The widespread use of tariffs usually leads to fewer imports. As other countries retaliate, exports decrease. Slowing global growth poses additional challenges to repatriating manufacturing to this country. If Trump can realize his passion, we may again return to those days of heady growth and more severe business cycle corrections.

////////////////////

Notes:

- The Case-Shiller home price index (HPI) for home prices. The Consumer Price Index’s rent of a primary residence.

- A NY Times account of Apple’s last attempt to manufacture in the U.S.A.