May 26th, 2013

Last week I wrote about the various benefits, particularly Social Security, that are based on the Consumer Price Index and the discussions about alternative measures of increases in the cost of living. The term “CPI” is a general term for a specific index, the CPI-U, a widely used index of prices for urban (hence, the “U”) consumers that the Bureau of Labor Statistics compiles.

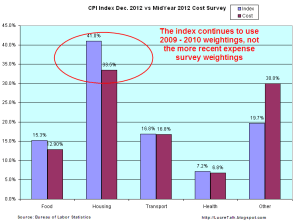

Today I’ll look at an alternative measure, the CPI-E, or Elderly index, which weights the expenditures of elderly consumers differently. Since the sample size of this population is relatively small, the BLS warns that it is more prone to sampling error, i.e. that the sample may not accurately reflect the characteristics of the entire elderly population. For the past decade or so, seniors have argued for cost of living increases in Social Security payments to be based on such an alternative measure. Using the latest BLS survey comparison data, I constructed a chart to show the differences in weighting of the larger components of the CPI-U, the commonly used index, and the CPI-E, the Elderly index.

Housing and medical expenses are weighted significantly higher in the Elderly index. A survey by the Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI) found that over 80% of 65 year olds own their own home. The mortgage component of total housing costs stays relatively steady for the younger group of elderly, yet the CPI-E that the BLS compiles shows a 4% increase in this component. The EBRI survey found that homeownership declines rapidly after 75, and it is this older group of the Elderly for whom housing costs rise. The question is whether the CPI-E can be properly sampled and compiled to show a more accurate picture of costs for the elderly.

The medical component of the elderly index is almost twice that of the general urban population. Although seniors have access to the subsidized Medicare program, the premiums for Medicare and costs not covered by Medicare are now borne by the elderly, rather than being fully or partially supplied as part of an employee benefit package. In addition, people access more medical care as they age. The combination of these two factors make it feasible that medical costs would be significantly higher for seniors.

Inaccuracies in measuring the housing component of the elderly index will be brushed aside by seniors receiving SS benefits. Whatever measure increases benefits – well, that’s the most accurate one, of course.

An interesting note is the change in recent years of housing costs as surveyed by the BLS. In 2007-2008, housing was 42% of total expenses. After the housing and financial crises, that component had dropped to about a third of total expenses. (Source)

But the December 2012 CPI-U index does not reflect the results of more recent findings of BLS personal expense surveys because they are using 2009 -2010 weightings. (Data)

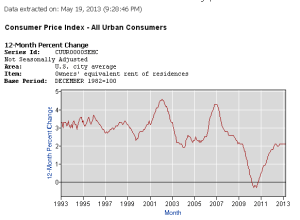

The largest part of the discrepancy between the actual changes in cost of living expenses and the published index is probably the “Owners Equivalent Rent” portion of housing costs which don’t reflect actual costs at all. Instead they are a calculation of what a home owner would have to pay herself to rent her own home from herself. No doubt, BLS economists would defend this phantom calculation as accurate but this calculation was never designed to allow for the precipitous drop in housing prices that we have experienced in the past few years.

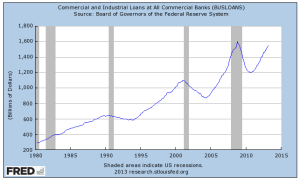

Based on BLS surveys of actual, not the adjusted, cost of housing changes, there is a good case to be made that the economy is experiencing a continuing mild deflation, not mild inflation. Deflation has become an ugly word. Social Security payments, labor contracts and a host of benefits are tied to the CPI and rely on the cost of living to increase, not decrease. Lawmakers in Washington have, in fact, mandated that Social Security payments can not decline if the CPI turns negative. Deflation is reviled almost as much as too much inflation. The Federal Reserve has a target of 2% inflation, meaning that it should start pulling money out of the economy if inflation rises above 2%. On the other hand, the Federal Reserve should be pumping money like there’s a five alarm fire if inflation has turned negative. Has the Fed been pumping money? Yes. Ben Bernanke, Chairman of the Fed, prefers to look at Real Personal Consumption Expenditures. Per capita expenditures have just now risen above 2007 levels.

While some inflation watchers are shouting “The sky is falling” as the Fed continues to pump money into the economy, Mr. Bernanke is looking at the big picture and its tepid. Tepid means fragile. Here’s the big pic of the last 15 years or so.

Growth has moderated. Bernanke has to be worried that low interest rates and continued purchases of mortgage securities by the Fed is helping inflate a stock bubble but he is equally concerned at the slower growth of the economy. Despite the headline CPI numbers of below 2% inflation, the reality is that it may be closer to 0% than the headline index indicates.

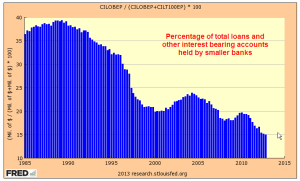

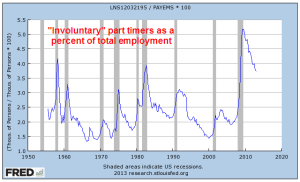

What’s behind that slower growth of spending? Look no further than something I write about each month, the lack of growth in the core work force, those aged 25 – 54. These are the people who buy stuff and if a smaller percentage of them are working, then they buy less stuff. Less stuff buying reduces inflationary pressures.