February 25, 2018

by Steve Stofka

Each week I’m hunting scat, the data droppings that a society of human beings leaves behind. This week I’m looking for a ghost ship called the Phillips Curve, a relationship between employment an inflation that has had some influence on the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy. The ideas and policies of others, some long dead, have a daily impact on our lives. I’ll finish up with a disturbing chart that may be the result of that policy.

A word on the word “cause” before I continue. As school kids we learned a simplistic version of cause and effect. Gravity caused my ball to fall to the ground. As kids, we like simple. As adults, we long for simple. As we grow up, we learn that cause-effect is a very complex machine indeed. The complexity of cause-effect relationships in our lives are the chief source of our disagreements.

So, “cause” is nothing more than shorthand for “has an important influence on.” The dose-response mechanism is a key component of a causal model in biology. If A causes B, I should be able to give more of A, the dose, and get more of B, the response, or a more frequent response.

Let’s turn to the Phillips Curve, an idea that has influenced the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy since it was proposed sixty years ago by economist A.W. Phillips. Simply stated, the lower the unemployment rate, the higher the inflation rate. There is an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation.

Inverse relationships are everywhere in our lives. Here’s one. The lower the air temperature, the more clothes I wear. I don’t say that air temperature is the only cause for how many clothes I wear. There is wind, humidity, sex, age and fitness, my activity level, social protocols, etc. While there is a complex mechanism at work, I can say that air temperature has an important effect on how many clothes I wear. If I measure the varying air temperatures throughout the year and weigh the amount of clothes that people have on, I will get a strong correlation. High temps, low clothes.

Now what if the temperature got colder and people still wore the same amount of clothes? I would need to come up with an explanation for this discrepancy. Perhaps there never was much of a relationship between air temperature and clothes? That seems unlikely. Perhaps clothes fabrics have been improved? I would need to look at all the other factors that I mentioned above. If I could find no difference, then I would have to conclude that air temperature had little to do with clothes wearing. Headlines would herald this new discovery. Important areas of our economy would be upended. Retail stores would stop stocking coats or bathing suits a few months in advance of the season. Businesses around the country who depend on warm weather clothing would go out of business.

Unlike air temperature and clothes, the relationship between inflation and employment is two-way. The change in one presumably has some influence on the other. During the 1970s, inflation and unemployment both rose. The hypothesis behind the Phillips curve posits that one should go up when the other goes down. Some economists threw the Phillips curve in the trashcan of ideas. Milton Friedman, an economist popular for his lectures and his work on monetary policy, proposed a concept we now call NAIRU. This is a “natural” level of unemployment. If unemployment goes below this level, then inflation rises.

Some economists complained that NAIRU was a statistical figment designed to fit the Phillips curve to existing data. Economic predictions based on the Phillips curve have been consistently wrong. Still, the Congress has mandated that the Federal Reserve maintain “maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates” (Federal Reserve FAQs). Economists at the Fed must consider both employment and inflation when setting interest rates. The models may not accurately describe the relationship, but many will instinctively feel that the relationship, in some form or another, is valid.

For the past several years, the economy has been at or near maximum employment. In January 2018, the unemployment reading was 4.1%. Whenever that rate has been this low, the country has either been at war or within a year of being in recession. The puzzlement: only lately have there been signs of an awakening inflation.

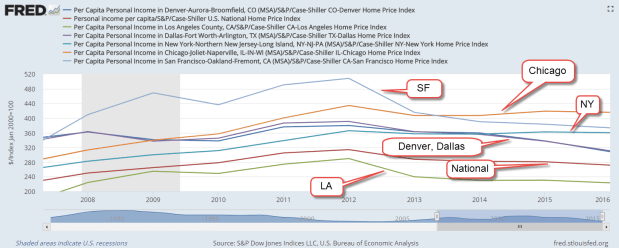

Because inflation was below the Fed’s 2% benchmark while unemployment declined, the Fed kept its key interest rate near zero for seven years. For its 105 year history, the Fed has never kept interest rates this low for as long as it did. Low interest rates fuel asset bubbles. Such low rates cause people and institutions who depend on income to take inappropriate risks to earn more income. The financial industry develops and markets new products that hide risk and provide that extra measure of income. We can guess that these products are out in the marketplace, waiting to blow up the financial system if a set of circumstances occurs. What set of circumstances? We will only know that in the rear view mirror.

Here’s a chart that tracks price movement of the SP500 ETF SPY for the past twenty years. I’ve shown the tripling in price that has occurred during the past five years. Notice the long stalk of rising prices. That growth has been nurtured by the Fed’s policy. Well, maybe this time is different. Maybe not.