February 25, 2024

by Stephen Stofka

This week’s letter is about the public’s expectations of inflation. The interest rate setting committee of the Fed indirectly controls the borrowing costs on our mortgages, credit cards and auto loans. The committee pays attention to public expectations of inflation because we respond now to what we see as potential threats. A fear of “making a mistake” in a job interview can make us nervous, increasing the chances that our behavior will decrease our chance of securing that position. A consumer who expects higher gas prices next year may buy a more fuel efficient vehicle this year.

Consumers must anticipate their future circumstances and income when they decide between different consumption bundles. Should they spend more on housing and live closer to work or get more house for their dollar and have a longer commute? Invest time and money in college, including the loss of income while attending school. Consumers must decide how much to spend and how much to save. Despite the difficulty of such decisions, many consumption choices are made on a shorter time scale than the suppliers who provide those goods and services. To survive, a business must live in the future, anticipating the trends of customer behavior that shape demand for its products or services. Since the pandemic, the shift to work at home has hurt many downtown businesses that depend on foot-traffic. There aren’t enough office workers to support some types of businesses.

In his General Theory published in 1936, John Maynard Keynes gave a prominent role to investor expectations. John Muth (1961) presented a more formal model that he termed “rational expectations.” In the 1970s, Thomas Sargent and Robert Lucas developed more extensive models to understand how people responded to the stagflation of the 1970s. The formation of expectations is an important economic variable and remains a hotly debated topic among economists.

Each month the New York branch of the Federal Reserve surveys a rotating sample of 1300 people to gauge their expectations of overall price changes as well as principle expenses like housing, food and gas (questionnaire pdf here). The Fed provides data on the past decade of surveys which allows us to assess changes in public expectations. As I explored this data with graphs, I was surprised at how closely expectations conformed to a textbook model that students are taught in an intermediate macroeconomics class. Macro is hard because there are few natural experiments to test theories and models. The pandemic led to a series of events that provided such a natural experiment.

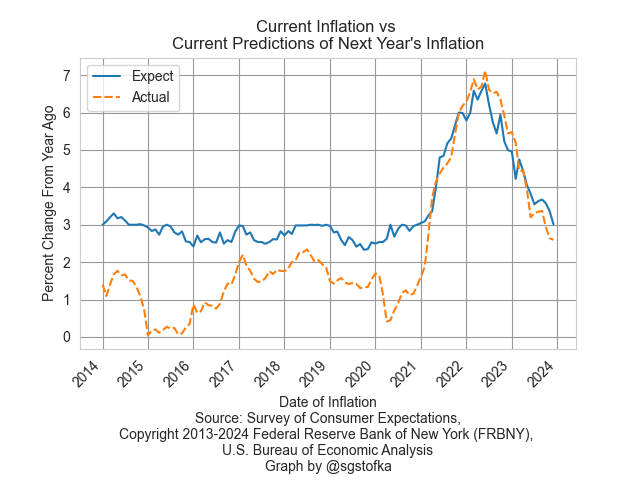

I’ll begin by comparing actual inflation to public expectations of inflation a year earlier. The first graph is actual inflation and the predictions of that inflation from a year earlier. From 2014 to 2020, the median value of expected inflation, the blue line, stayed anchored in the 2.5% to 3% range even when actual inflation, the orange dotted line, was below that. Lower inflation was not a threat to people’s pocketbooks so there was little reason to revise their estimates downward. We have a well-studied risk aversion, meaning that we place greater weight on loss than we do on gains. In this case, lower than expected inflation is a gain. Economists and the general public were both caught off guard when inflation surged higher in 2021.

As soon as inflation rose above long-term averages, as it did in 2021, survey respondents revised their estimates of next year’s inflation. Higher inflation is a threat to our finances, so we pay greater attention. However, survey respondents based their estimates of next year’s inflation on this year’s actual inflation. Is that a good estimating procedure? Maybe not, but estimating trends requires knowledge, practice and error checking to improve our skills. Many times we use shortcuts, called heuristics, instead. I will leave a textbook explanation of the formation of inflation expectations in the notes.

How do we survive using shortcuts? One of those shortcuts is our degree of uncertainty. There are fewer traffic accidents at roundabout intersections because they introduce a degree of uncertainty that causes us to be more cautious. The median percent of uncertainty jumped in March 2020 when pandemic restrictions were announced. When Biden took office a year later uncertainty remained at this elevated base. As the economy reopened in the spring of 2021, supply disruptions became apparent. “When are you going to get more of these in stock” was met with “We don’t know. They’re on a boat somewhere in the Pacific.” While people sat at home during the pandemic, they bought a lot of goods from online retailers like Amazon. The reopening of service-oriented businesses caused another price shock as the economy transitioned from goods-heavy back to one that relied heavily on services.

The peak of uncertainty occurred in mid-2022, shortly after the Fed began a series of consecutive interest rates increases that would lift the benchmark lending rate by 5%. The uncertainty of survey respondents decreased in reaction to the Fed’s intention to keep increasing rates until rising inflation was tamed. I’ll zoom in on the past three years of uncertainty and the Fed’s “get serious” campaign of interest rate increases.

Despite criticism of the Fed, its intentions were credible to the public. Expectations are as difficult to measure as animal pheromones but they are real. They cause responses. Surveys are an imperfect gauge of expectations but they will have to do until someone invents an expectarometer that detects the mental disturbances in the sub-ether caused by expectations. That’s a world similar to Philip K. Dick’s Minority Report and I’m not sure we want that.

////////////////////

Photo by Jan Huber on Unsplash

Keywords: federal funds rate, inflation, expectations

Note on inflation expectations: A textbook explanation is

πet = (1- θ)π̅ + θπt-1, or in words

πet is current expectations of future inflation,

π̅ is average inflation,

θ is the weight people give to recent inflation πt-1 (Blanchard, 2017, p. 162).

From 2014-2020, survey respondents gave little weight to recent inflation, such that θ was close to 0 and expectations of inflation were close to a long-term average. As soon as inflation rose above the long-term average, θ went quickly to 1, resulting in an equation that looked like πet = (1-1)π̅ + 1π̅t-1 which simplifies to the most recent reading of inflation.

Blanchard, O. (2017). Macroeconomics (Seventh ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Muth, J. F. (1961). Rational Expectations and the Theory of Price Movements. Econometrica, 29(3), 315-33512