September 29, 2024

By Stephen Stofka

This week’s letter is about voting. Many voters believe that their election choices are rational, based on their values, principles and self-interest. Some economists and political scientists think that our rationality is bounded. We make decisions using heuristics – a “good enough” approach that saves us time and effort. Election choices are guided by self-identification, by tradition, by allegiances. We make irrational decisions but in predictable ways because our choices are anchored by our cultural beliefs, our emotional reactions and cognitive assessment (Pindyck & Rubinfeld, 2017, 261).

Some people are single-issue voters, whose vote is guided by one policy or principle. Their choice of political party may rest on a belief in more government or less government, on more or less taxes, on more or less access to abortion, on more or less tolerance of immigration. The political parties do not want to resolve these hot issues because they drive voters to the polls.

A person’s election choice may be guided more by principal than financial self-interest. A lower income voter might pay little federal income tax but thinks the progressive income tax system is unfair. They vote for a party that promises to make the tax system less progressive even if it means that they may have fewer federal benefits or pay higher taxes. A voter’s choice of presidential party may rest on a local issue like property taxes or zoning regulations. National parties do not control zoning regulations, but they do signal a set of attitudes. Those attitudes help build a coalition of voters who share that perspective.

Let’s imagine that you, dear reader, are not the sort to take shortcuts. Election choices have consequences for an individual’s savings. Remove your Republican or Democratic hat and don the hat of a financial manager who has a fiduciary duty to their savings. If you have watched the TV series Clarkson’s Farm, now in its third season on Amazon Prime, you are aware that Jeremy Clarkson, the owner of the farm, has an experimental spirit and an ambitious imagination. Charlie Ireland, the farm’s land agent, offers a sobering contrast to Jeremy’s enthusiasm. Charlie is familiar with the prices of farm commodities and the average costs to produce those commodities. Charlie can do arithmetic in his head. Jeremy uses a hand-held calculator. Charlie presents Jeremy with a forecast of the disappointing (often) profits that will emerge from the many hours of hard work on a farm. Put on Charlie’s hat. Your goal is to present the facts to yourself, the owner of a farm called your portfolio.

Does the party affiliation of the president have an effect on the returns of the SP500 index? A financial forecast relies on historical data and cannot account for future events. The likelihood of more or less portfolio gain might have no consequence but it is helpful to be prepared. During a 4-year term, what are the expected average yearly gains in a stock index like the SP500? I will start with the presidency of Bill Clinton who began his two-term presidency in January 1993. The worth of a portfolio is what it can buy so I will use an inflation-adjusted index.

Two Democratic presidents, Clinton and Obama, had the highest annual gains. Both Obama and Biden began their terms under severe economic duress after a previous Republican administration. Clinton faced an economy with lackluster employment growth less than 1% following a mild recession two years before he took office. Trump had the third highest annual gains, helped by a relief rally at the prospect that his chaotic term was ending. In the three months after the 2020 election, the index gained 8.25%, an annualized gain of 33%. Now remove the accountant hat and don the voter hat. Does any of this information change your mind? Probably not.

Do you vote for the party that will lower your taxes? Don your accountant hat again and look for the average effective income tax rate. That’s the income taxes paid as a percentage of adjusted gross income. As the table below shows, the effective rate is about 15 – 16% in normal years. A crisis year like the invasion of Iraq, the financial crisis and the pandemic cuts the effective rate by 10%. Incomes and capital gains are reduced. All three crises occurred under a Republican president.

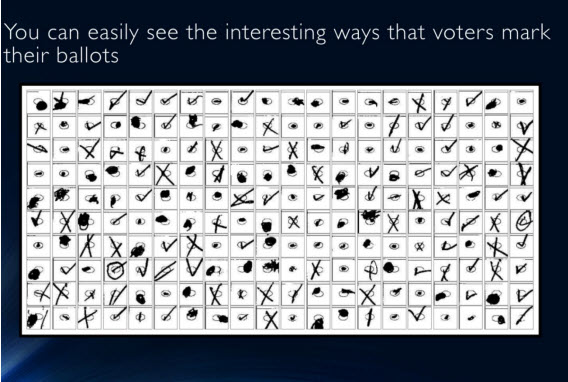

Real life is not a Hollywood script. The evidence is not decisive. We should put our accountants’ hat in the file drawer on election day and use our customary shortcuts. Some voters make one of two alternative choices. Out of disinterest or disgust, some don’t vote. In a presidential election, some undervote, choosing candidates down the ticket but leaving their choice for president blank. The Election Audit Commission (pdf here) notes that an election official may have to inspect a ballot in case automated software cannot read a voter’s mark. Here’s a picture showing the many different ways voters have marked their choices (p. 13).

In the 2012 election, 1% of voters left their presidential choice unmarked, according to a USA Today analysis. In 2016, it was almost double that percentage – 1.9%. Recent polls indicate a tight race between Trump and Harris. As happened in 2016, a small number of voters in several key states could decide the election. In the 2000 Presidential election, several hundred Floridian voters mistakenly marked Buchanan for president instead of Gore. Some realized their mistake, crossed out their initial mark and voted for Gore. This resulted in an overvote for two candidates on the same ballot. In many cases, this voided the voter’s choice entirely.

Over $14 billion was spent in the 2020 election campaign, according to Open Secrets. In a nation of millions of voters, it is irrational that a few thousand voters or less should decide an election. Last week, I referred to John Bates Clark, a 19th century economist, who asked why a small surplus of wheat in the northwest should determine the price of the entire wheat harvest. In a “winner-take-all” fashion, 48 states award all their electoral votes to the candidate who gets the most votes. A few thousand votes may decide all the electoral votes in a state. Why should a person make a rational choice when an idiotic election system neutralizes their careful deliberation?

//////////////////////

Photo by Giorgio Trovato on Unsplash

Pindyck, R. S., & Rubinfeld, D. L. (2017). Microeconomics. Pearson Education Limited.