January 28, 2024

by Stephen Stofka

This week’s letter is about the decisions people make in connection with their compensation. Guided by the strength of the job market and expectations of inflation, employees seek higher compensation by switching jobs or by wage and benefit demands. Like fish in the sea, these individual decisions form schools that follow and shape the currents of economic growth and inflation.

There are two main components to employee compensation. The first category includes wages or salary, some of which is reduced by income and FICA taxes. The amount left over is called disposable income. The second component of compensation is loosely categorized as benefits that are already dedicated to a single purpose and are non-disposable. These include paid time off, pension plan contributions and health care. They also include government mandated taxes that the employer pays for the employee. These include workers’ compensation, unemployment insurance and the employer’s half of FICA taxes. Except for paid time off, employees do not pay income taxes on benefits.

As I noted last week, the Bureau of Labor Statistics calculates an Employment Cost Index (ECI) that includes both wages and benefits. This composite can give us different insights than tracking the growth of wages alone. Comparing the ratio of the wages portion to the total index allows us to spot trends when wages grow more than benefits or benefits grow faster than wages. I’ll call this the Wage Ratio.

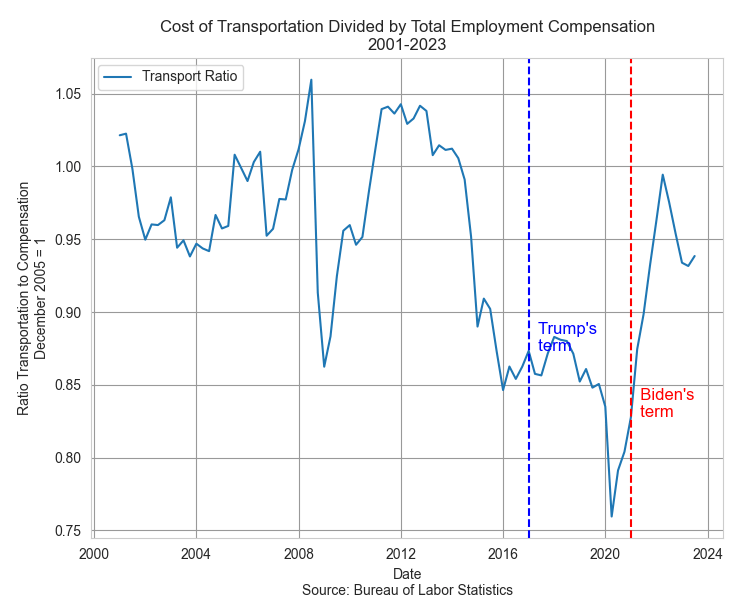

In the chart below, we can see three distinct periods: 2001 through 2007, 2008 through 2015, and 2016 through 2023. In the first and third periods, wages grew faster than benefits but their growth patterns are distinct. In the first period growth was coming into balance with benefit growth. In the third period, wage growth was accelerating. In both periods there was a strong correlation between the wage ratio and an inflation measure that the Fed uses called PCE inflation (see notes).

When inflation is low, employees may desire more of their compensation in benefits. Most of these are tax-free so employees get more “bang” for each dollar of benefit. In the second period, there was a rebalancing of wages and benefits. As the nation recovered from the housing and financial crisis, low inflation reduced the pressure to seek higher wages. During the last year of Obama’s second term in 2016, that inflation rate began to rise from near zero to 2%. The Fed raised its key interest slightly above zero, happy to finally see inflation nearing the 2% target rate that the Fed considers healthy for moderate growth.

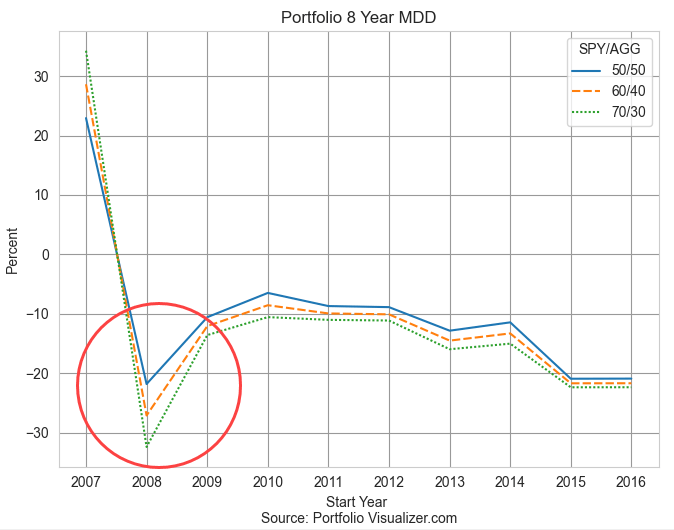

The Fed also has a target for its key interest rate that is 2% or above. For eight years it had kept that interest rate near zero to help the economy recover after the financial crisis. The Fed knows that such a low rate has two disadvantages. It gives the Fed less room to respond to economic crises because they cannot adjust rates lower than the Zero Lower Bound (ZLB). Secondly, sustained near-zero rates lead to high asset valuations, or bubbles, which are disruptive when they pop. The housing crisis was a recent example of this.

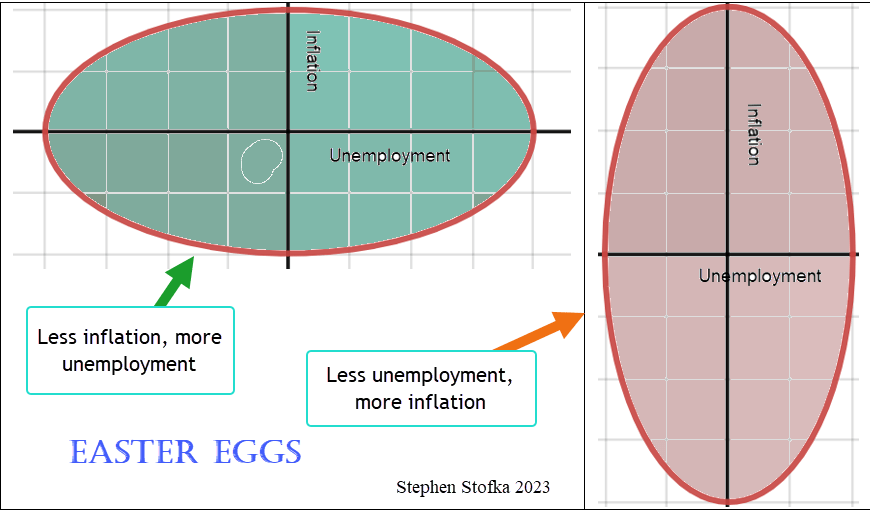

During the first three years of the Trump presidency, inflation leveled out near that 2% target rate as the Fed continued to raise rates in small increments, finally ending near 2.5%. In 2018, Trump went on a tirade against the Fed, accusing it of sabotaging his Presidency. Low interest rates had fueled an annual rise in housing prices from 5% at the end of Obama’s term to 6.4% in the first quarter of 2018. Trump was not the first President who wanted a subservient Fed willing to enact policy that enhanced the Presidential political agenda. Because a President wins a general election, they may convince themselves that their desires reflect the general will. They do not. Congress gave the Fed a twin mandate of full employment and stable prices to separate Fed policy from Presidential control. It did so after several episodes where Fed policy served the desires of the President rather than the public welfare.

In 1977, Biden was in the Senate when Congress enacted the legislation that gave the Fed a twin mandate. Unlike Trump, Biden has not pounded his chest like a belligerent gorilla as the Fed raised rates by five percentage points within a year. The results of the Republican primaries in Iowa and New Hampshire make it likely that this year’s election will be a repeat contest between Biden and Trump. The Fed has hinted that they might lower rates this year if inflation indicators remain stable and the unemployment rate remains low. That would be the proper response and in accordance with the Fed’s mandate.

Should the Fed lower rates even a small amount, Trump will certainly complain that the Fed is helping Biden win re-election. He will protest that “the system” is opposed to him and his MAGA supporters. If Republicans can gain control of both houses of Congress and the Presidency this November, Trump will likely pressure McConnell to change the cloture rule so that Senate Republicans will need only a majority to pass a bill making the Fed an agency subject to Trump’s control. In 2022, seven Republican Senators introduced a bill to condense the number of Federal Reserve banks and make their presidents subject to Senate approval. Should the Fed lose its independence from political control, we can expect the high inflation that has afflicted Venezuela and Argentina, countries where a political leader has used monetary policy to win political support. Workers will demand higher wages to cope with rising prices and those demands will help fuel the inflationary cycle. We actualize our expectations.

/////////////////

Photo by Erlend Ekseth on Unsplash

Keywords: inflation, wage growth, housing prices, Fed policy, monetary policy

Correlation: In the eight year period from 2001thru 2008 when wage growth was high but declining, the correlation between inflation and wages was -.63. From 2016 through 2023, as the wage ratio was rising, the correlation was .85.