August 14, 2022

by Stephen Stofka

The National Association of Realtors (2022) publishes a Housing Affordability Index (HAI) that measures median housing prices, mortgage rates and median family income to determine a ratio of housing costs to family income. June’s index was the lowest affordability since 1989. Since the Fed began raising rates this year, affordability has fallen by a third. In the notes I’ll include some comments on the methodology behind the HAI.

With technological progress, we expand our definition of what is a necessity. We argue whether government has a responsibility to ensure that each family has a certain level of sustenance – adequate housing, food, a source of income and access to educational resources. Those in neighborhoods with single family homes resist efforts to build affordable multi-family housing. A real estate developer earns a higher profit building expensive townhomes than affordable housing units. Should a developer be compensated if required to build affordable housing? City councils would prefer not to bring up the subject of using tax money to compensate a developer for doing less.

We disagree about who should pay, who should get and how much. Several decades ago, the homeless were less visible, a huddle of a human being lying under a tree or on a park bench, occupying about 18 square feet. In destination cities like Denver, Portland, L.A and other western states, encampments of homeless in colorful pop-up tents line downtown sidewalks and along streams and rivers that course through the town. Depending on the size of the tent each person may occupy up to 50 square feet. Like the rest of us, they are taking up more space per person. Are there more homeless or are they simply more visible?

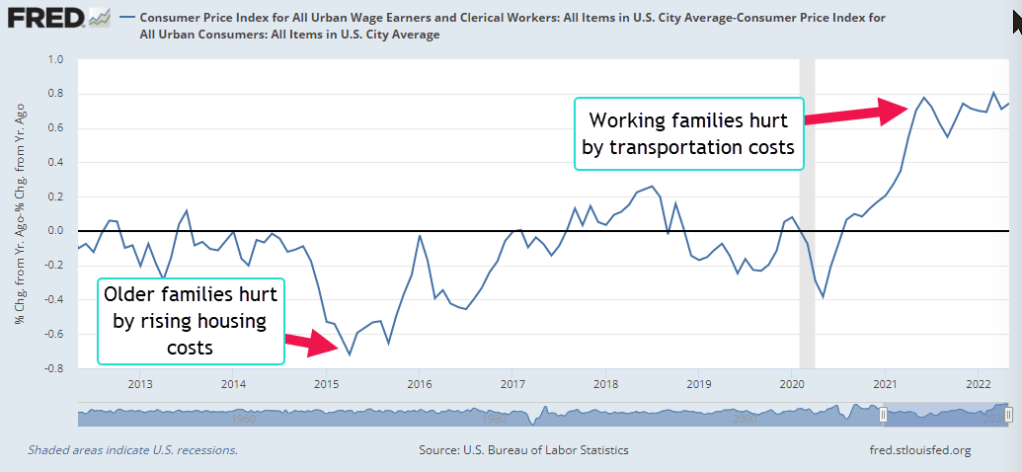

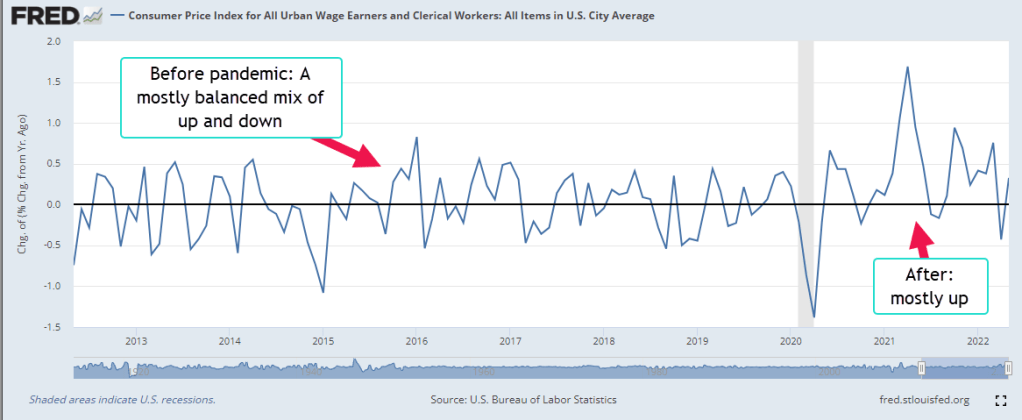

The reasons why people are homeless are numerous and varied but the dynamics of housing supply and demand are key factors. Where demand for rental housing is low, landlords of affordable units may skip a criminal background or credit check. When demand is high, rents are higher and landlords are more discriminating. They may require higher security deposits as a tool to screen out renters. The annual change in rental costs was 6.3%, below the 7.3% increase in housing costs but workers’ wage increases have not kept pace in the past year. (I’ll put the series identifiers and index numbers in the notes at the end). Over a long time period, have earnings kept up with housing costs?

I began with 1973, the year that the U.S. and most of the world adopted floating exchange rates between currencies. This allowed capital more freedom to move around the world. Several economists mark that as a turning point when the returns to labor began to lag behind the returns to capital. Today’s workers make $612 for every $100 that workers made in 1973, a 6:1 ratio. Housing costs have risen even faster. The Bureau of Labor Statistics calculates that a person spends $888 for shelter today for each $100 spent in 1973. In computing the CPI, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2022) and the Census Bureau include mortgage payments, taxes and insurance – PITI – to determine the cost of shelter itself (32% of income), about 5% for utilities and another 5% for maintenance and repairs. Together they make up more than 40% of a family’s income.

We measure things in order to compare qualities. An example might be measuring the width of a bookcase and the width of a space in the living room where we want to put the bookcase. Comparing total housing costs across five decades is difficult. We prefer to live in bigger spaces and in far greater comfort than we did 50 years ago. Today’s new homes average 2600 SF. The thirty year average is 1800 SF. Moura et al (2015) estimated that each of us has twice the space of a person living in 1900. Total housing costs may have grown almost 50% faster than wages but per capita housing space has grown at least as much. Adjusting for the larger personal space, we could conclude that wages have kept up with total housing costs. But that’s not how many of us perceive affordability. More space and comfort has become our standard.

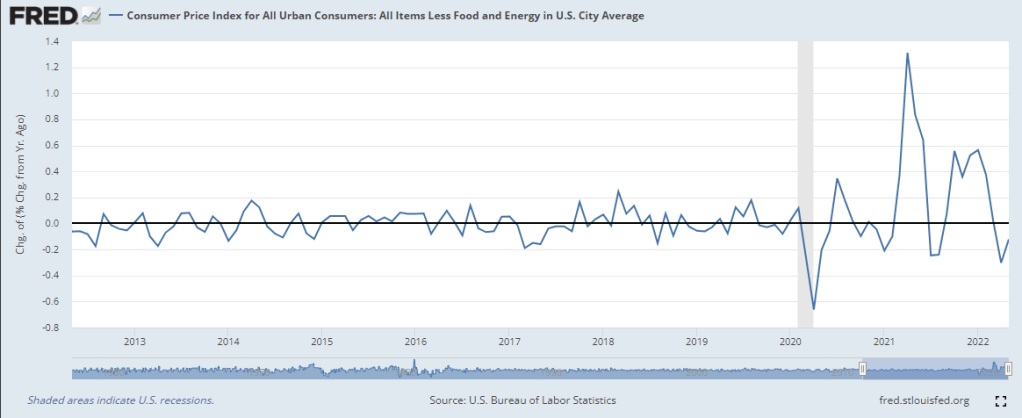

Changing standards and expectations cause a shift in definitions and benchmarks. The BLS includes the cost of cell phones, computers and internet access under Information and Information Processing. Many families consider these to be utility expenses as necessary as the heating and electric bill. The BLS estimates a family spends 3.5% of their income on these modern day necessities – about $3000 a year. TV cable subscriptions add another 1%. Five decades ago, a family had a $0 monthly cost for these. Together that cost represents $320 per month that impacts housing affordability. The cars we drive today are safer, more mechanically reliable and more fuel efficient but we spend more of our income on transportation costs. In the post-war period, food and clothing were almost half of a typical family’s expenses. Today those items make up just 13% of a family’s spending (BLS, 2014). We live in bigger homes because other items that used to take up a lot of space in our budget have shrunk.

News media often puts current economic measures in historical context – the highest since and the lowest since – but these quantitative measures are not adjusted for improvements in the qualities of goods. On a hot summer’s day five decades ago, there might have been several overheated cars on the drive home from work. Changing a flat tire on the side of the road was common. Automobile deaths were far higher. Older people died from heat exhaustion in uncooled apartments and homes. Our standards and expectations have changed.

Each month economists measure thousands of data points – as numerous as the stars in the night sky. Economists and politicians connect those dots using different paths of reasoning, motivation and perspective. We may cling to a particular doctrine that clouds our interpretation of the data. In the end economic issues are personal. Have our earnings kept up with our housing costs?

////////////////

Photo by Tierra Mallorca on Unsplash

BLS. (2014, April). One Hundred Years of price change: The consumer price index and the American Inflation Experience : Monthly labor review. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved August 12, 2022, from https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2014/article/one-hundred-years-of-price-change-the-consumer-price-index-and-the-american-inflation-experience.htm

BLS. (2022, February 11). Relative importance of components in the Consumer Price Indexes: U.S. city average, December 2021. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://www.bls.gov/cpi/tables/relative-importance/2021.htm

Lautz, J. (2022, January 7). Tackling home financing and down payment misconceptions. http://www.nar.realtor. Retrieved August 12, 2022, from https://www.nar.realtor/blogs/economists-outlook/tackling-home-financing-and-down-payment-misconceptions

Moura, M. C., Smith, S. J., & Belzer, D. B. (2015). 120 years of U.S. residential housing stock and floor space. PLOS ONE, 10(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134135

National Association of Realtors (2022). Housing affordability index. http://www.nar.realtor. Retrieved August 12, 2022, from https://www.nar.realtor/research-and-statistics/housing-statistics/housing-affordability-index. As constructed, an affordability index of 100 should be affordable. However, the NAR calculates a mortgage payment that is not typical. They base their calculation on a 20% down payment. The average down payment is only 10%. First time buyers typically put down only 7% (Lautz, 2022). This raises the mortgage payment and lowers the affordability. After adjusting for this, an HAI reading of 140 is probably a better benchmark of affordability.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Housing in U.S. City Average [CPIHOSSL], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIHOSSL, August 13, 2022. July’s annualized increase was 7.3% and climbing.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Rent of Primary Residence in U.S. City Average [CUUR0000SEHA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CUUR0000SEHA, August 13, 2022. July’s annualized increase was 6.3% and climbing.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Shelter in U.S. City Average [CUSR0000SAH1], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CUSR0000SAH1, August 12, 2022. Note: Total cost of shelter was 39.90 in April 1973 and in 2022 it is 354.45, an 8.88 ratio.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Average Weekly Earnings of Production and Nonsupervisory Employees, Total Private [CES0500000030], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CES0500000030, August 12, 2022. In July 1973 the index was 153.14. In July 2022 937.38. A 6.12 ratio.