June 5, 2022

by Stephen Stofka

This week Janet Yellen, the current Secretary of the Treasury and former Fed Chair, admitted that she had not understood the path inflation would take. Such honesty from an administration official is refreshing. Ms. Yellen joins a long list of smart and experienced money managers who did not forecast this inflation trend. Global pandemics happen once a century, producing economic shocks that are unpredictable.

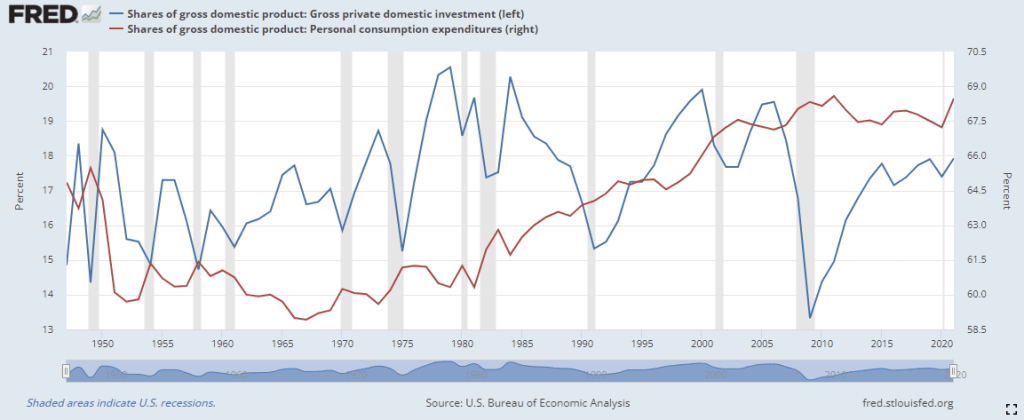

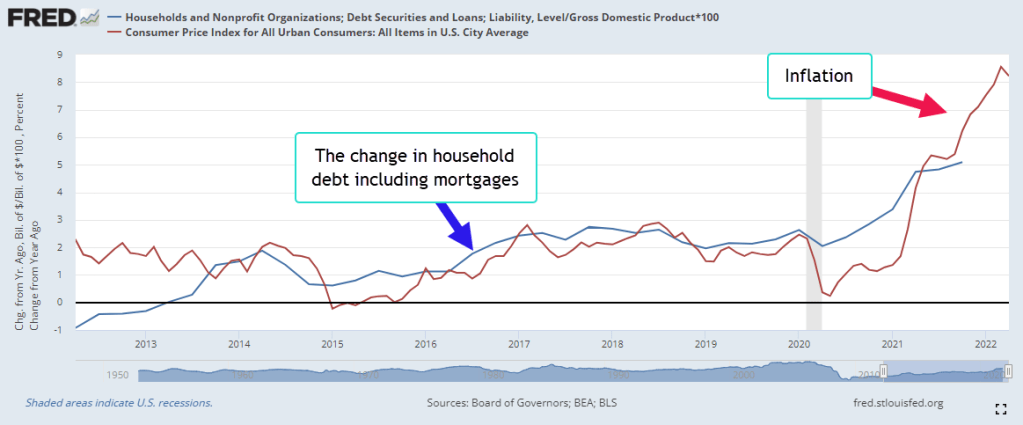

The economist Milton Friedman attributed inflation to money growth. Who grows money? Banks. The central bank (Fed) may increase the base money[1] it makes available to its member banks but it is the banks who multiply that base money when they make consumer and business loans. In the past decade, the annual percent change in household debt has tracked closely the rate of inflation. As long as banks were reluctant to extend credit, inflation remained low. The CARES act transferred billions to consumers and banks followed the money, extending more credit and shifting consumer demand higher.

For more than a decade sales of consumer durables excluding cars (ADXTNO) had waned. Pandemic restrictions forced us to alter our consumption habits and we bought durable goods for a new stay-at-home lifestyle. These included computers, dishwashers, refrigerators, and workout equipment. Our collective actions produced positive and negative effects. There is no one individual responsible for the negative impacts so we have blamed government policies or politicians.

Our collective actions change our physical and economic environment. Like a forest fire, we create our own weather and that feedback process can amplify the destructive forces of our actions. Adam Smith, the first economist, lived at a time when people were clustering in communities to trade with each other and engage in collective production. He was the first to note the dynamics of labor specialization where the productivity of individual effort is magnified and the entire community benefits from the assembly of coordinated effort.

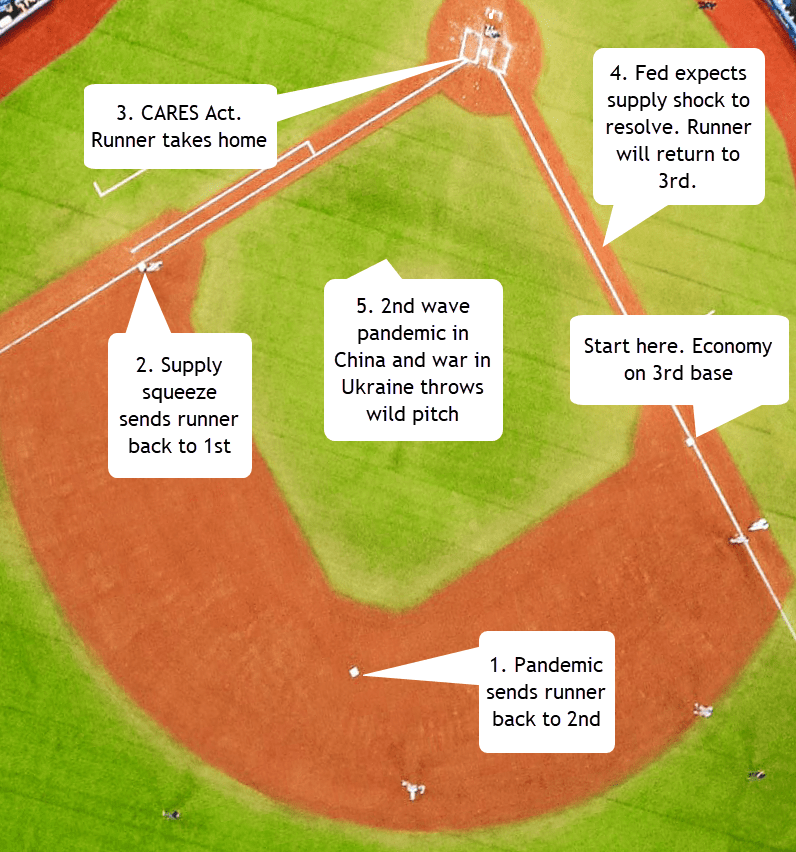

As our population grows and concentrates in larger communities, group dynamics have a greater influence in our individual lives. Fashionable ideas and perspectives sweep through our society as easily as new product innovations. Social media speeds the introduction and adoption of trends. Under normal circumstances, the global supply chain adapts to these demand shifts rather quickly. However, the supply chain relies on a continuous flow of goods and services. The pandemic interrupted that flow, inducing a supply shock into the economy.

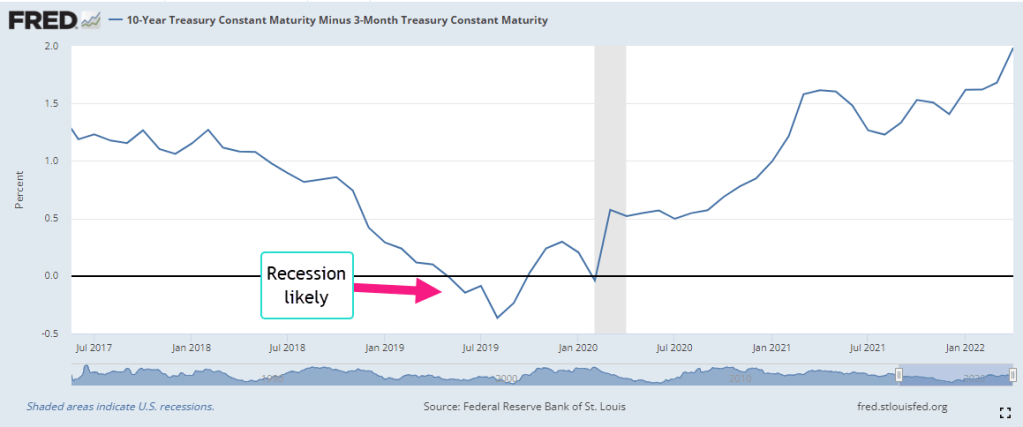

As economic activity returned to normal during 2021, investors and policymakers thought that supply chain disruptions would ease. Market prices increased about 20%. In January 2022, companies reporting 4th quarter results indicated that supply chain problems were slow to resolve and anticipated higher prices in 2022. Thousands of very smart people revised their earlier forecasts and adjusted their portfolio positions.

One of our favorite pastimes is armchair quarterbacking. We do it with ourselves as much as we do it with others. Reviewing a test score, we are sometimes surprised by a dumb mistake we made. Many of us gravitate toward jobs with a greater degree of familiarity and predictability. There is less stress and less likelihood of making mistakes. Some jobs are like daily tests with multiple selection choices and the answers are not certain. The lessons emerge as events unfold and lack what statisticians call external validity. The lessons learned or principles identified cannot be generalized to other situations because of important differences. Top administration officials and those in upper company management have those kinds of jobs.

/////////////

Photo by Ben White on Unsplash

[1] Base money refers to reserve money that is available only to banks.