March 27, 2022

by Stephen Stofka

The 2024 presidential election is still far away but a 75 year political trend is surprisingly predictive of election results. Add in one economic indicator and the results are even more predictable. An incumbent president won re-election 8 out of 12 times, or 67%. Those who lost failed to jump the hurdle of unemployment. When there is not an incumbent president, voters have changed parties in 6 out of 7 elections. America spends billions of dollars on election campaigning but voters have busy lives full of many choices. As with many decisions, we follow a few simple guidelines. Here’s a guide to winning the next election.

American voters like change but they usually play fair. When the annual (year-over-year) change in unemployment is falling (UNRATE note below), incumbent presidents are assured of a second term. I’ll refer to that change as ΔU. If that change is falling, then employment is improving and voters don’t kick someone out of office. Let’s look at some recent history to understand the trend and those few times when political issues overshadowed economic trends. At the end of this article is an earlier history for Boomers and political history buffs.

In 1992, the ΔU did not favor incumbent Republican President H.W. Bush in the long stuttering recovery after the 1990 recession. In the 18 months after the end of the first Gulf War ended in early 1991, his approval numbers sank from very high levels. A third party candidate Independent Ross Perot focused on economic issues and diverted a lot of moderate and conservative votes away from Bush, helping to put Democratic candidate Bill Clinton in the White House with only 43% of the popular vote. Unemployment numbers favored Clinton in his 1996 re-election bid and voters awarded him a second term.

By 2000, the great internet bull market was wheezing. Unemployment was rising and did not favor Democratic VP Al Gore as he sought to succeed Clinton. A few hundred votes in Florida separated Gore and his opponent, former Texas Governor George Bush. A partisan Supreme Court made a radical decision to overrule the Florida Supreme Court and award the election to Bush, switching party choice yet again. If the employment numbers had been more favorable to Gore, voters might have been inclined to keep him at the tiller.

Bush’s approval soared after the 9-11 attack but controversy erupted when he decided to attack Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein on the pretext that the country had weapons of mass destruction. When no weapons were found, his ratings sank. The economy had stumbled after the short recession of 2001 but tax cuts in 2003 helped employment numbers recover. Bush avoided the fate of his father and won re-election.

As the housing crisis grew in the spring of 2008, the unemployment numbers turned ugly. Again voters changed parties and elected the Democratic candidate Barack Obama. Despite Obama’s unpopularity over health care reform, the unemployment numbers helped Obama to a second term over challenger Mitt Romney. After two terms of a Democratic president and knowing voters like change, a gambler would put their money on a Republican candidate in the 2016 election. The employment numbers favored the Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton, who won the popular vote. A few thousand votes in key states turned the tide in Donald Trump’s favor. Again, we learned the lesson that employment numbers assure victory for an incumbent president but not the incumbent political party.

In 2020, the pandemic drove the change in unemployment to stratospheric levels, rising 9.3% from 2019 levels. Both parties responded with legislation to stem the shock and economic pain to American households. Despite those historically unfavorable unemployment numbers, Trump increased the Republican vote count but could not overcome a larger surge in Democratic votes. The unemployment numbers in the quarters before the pandemic favored Trump. Had the pandemic not struck, it is likely that he would have won re-election.

Memo to incumbent presidents: If unemployment is rising you won’t win re-election.

Given that history, an incumbent Party should enact fiscal policy that keeps or lowers unemployment in an election year. An opposition party should try to block any such legislation. After the 2008 election, the country was suffering the worst recession since the Great Depression and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said that his goal was to make newly elected Democratic candidate Barack Obama a one-term president. McConnell was vilified for his partisan remark during a time of crisis but he stated the political reality that elections are a zero sum game. At the time of the August 2011 budget crisis between Republicans and the White House, the ΔU was a solid ½% negative. Falling unemployment hurts the election chances of the opposition party. The realities of democratic elections are uglier than many voters can stomach but we are carried along on those currents.

If unemployment is rising toward the end of 2023, look for Democrats to enact fiscal spending that will put people to work. To improve their own chances, watch for Republican strategies that will block any such measures.

////////////

Photo by Gene Devine on Unsplash

UNRATE Note: Unemployment is the headline number, averaged over each quarter. The year-over-year change is taken in the 2nd quarter of an election year (April – June) before each political party conducts its convention to choose their candidate.

/////////////

For interested Boomers and history buffs:

Near the end of WW2, 4-term Democratic President Roosevelt died and his VP Harry Truman assumed the Presidency. In 1948, the unemployment numbers looked grim as the economy tried to absorb millions of soldiers returning from war. Pre-election polls had favored Truman’s opponent, Thomas Dewey, and one newspaper printed out a headline on election night that Dewey had won but that announcement was premature. Truman’s victory is the only time an incumbent has won re-election when unemployment numbers were unfavorable. When the final results were announced, Truman famously pointed to the newspaper’s false headline. Perhaps that is the first time when a politician called out “fake news.”

In the spring of 1952, incumbent Democrat President Truman’s ratings were falling. The ΔU was neutral but the trend was against Truman. When he lost the New Hampshire primary to another Democratic candidate, he retired to his home in Missouri. Republican Dwight Eisenhower won the election. In 1956, the unemployment numbers favored “Ike” and voters gave him another term. In 1960, the ΔU had turned against Ike’s aspiring successor, VP Richard Nixon. Voters switched parties, choosing JFK, a Democrat, in a close and contentious election.

After Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, the unemployment numbers were strongly in favor of President and former VP Lyndon Johnson, who rode the wave of favorable sentiment to the White House. In the spring of 1968, the ΔU still favored Johnson but voter sentiment was more focused on the Vietnam War and Johnson decided not to run for re-election just as Truman had chosen 16 years earlier. Richard Nixon’s political fortunes resurrected on his promise to end the war with dignity and voters changed parties.

In 1972, unemployment favored Nixon who regained the White House, only to leave a few years later to avoid impeachment and ejection from office. In 1976, unemployment numbers looked good for Gerald Ford, who had assumed the presidency. However, he could not overcome voter hostility after he pardoned Nixon for the crimes revealed during the Watergate hearings. Incumbency and favorable employment numbers are powerful persuaders but there are a few times when voters concentrate on political matters more than economic considerations.

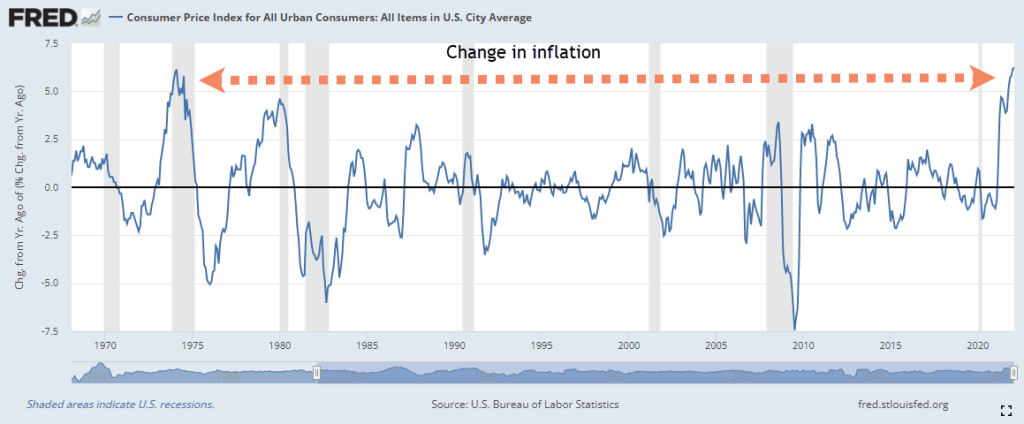

Jimmy Carter, a Democrat, took the White House but couldn’t keep it as both unemployment and inflation were rising in 1980. Republican winner Ronald Reagan had often asked “Are you better off today than you were four years ago?” In 1984, unemployment was still high but falling by 2.7% and Reagan won in a landslide. 1988 is the only election in which the voters did not change parties after two terms. Unemployment was falling and voters turned to VP H.W. Bush for his turn in the top job. Unemployment is a decisive factor in re-electing an incumbent but not enough to overcome the American inclination to political change every decade.

The history continues in the main part of the article.