May 12, 2013

We can take some steps to reduce our susceptibility to adverse events but if our primary aim is to reduce uncertainty as much as possible, our lives suffer in quality and our wallets suffer in quantity. In our financial lives, we must try to find a balance between risk and reward. There is a high demand for low risk, high reward investments. Unfortunately, there is little supply of such investments and the few that are offered are usually scams.

There is a good supply of low risk, low return products. In the past ten years, conservative savers have taken a beating. There have been only two periods where the interest on one year CDs has exceeded the percentage increase in inflation.

Challenged by low interest rates on CDs, savers have fled the market.

Older people who rely on their savings to generate income continue to search for yield, or the income generated by an investment. The iShares High Yield Corporate Bond ETF, HYG, and the iShares Dividend Select Index ETF, DVY, have posted strong gains. As more investors chase yield and drive up prices, the yields correspondingly become lower. In December 2007, DVY paid out an annualized 4.7% yield on a price of about $53. In March 2013, the yield was 3.4% on a price of $65 (Source)

Despite the fact that the Federal Reserve has held interest rates at historic lows, the amount of household savings continues to climb. Some of this is due to an aging population which has more in savings and tends to be more conservative.

The Federal Reserve is essentially kicking people out of the tent and into the forest where the wild animals live. It’s risky out there in the forest. How come the banks don’t want our money? Some people do not realize that a CD or savings account is essentially a loan to the bank. Through the FDIC, the U.S. government insures most of these loans. Loan your brother in law money for a year and you might not get it back. Loan your bank the money and you are assured that you will get it back.

In the simplified models of banking we learned in grade school, the bank pays us interest for the money we loan it (deposits) and loans that money out to other people at a higher rate of interest. The difference in the two interest rates is how banks pay their employees and other business costs and make a profit. The reality is much more complex. A bank does not take a $10 deposit from Mary and loan it to Joe. The bank takes the $10 deposit from Mary and loans $100 to Joe. Where did the other $90 come from, you ask? It is created out of thin air in a process called fractional reserve banking, which allows a bank to leverage the $10 deposit by ten times, in this example. Because banks are leveraging money, there is a labyrinth of financial metrics of stability to insure that the banks are not taking too much risk. Some of these metrics include the risk weighting of assets (deposits, loans and securities, for example) and capital asset ratios.

In a 1985 paper by Federal Reserve economists, they note that “There is remarkably little evidence, however, that links the level of capital or the ratio of capital to assets with bank failure rates.” This paper was written before the S&L crisis of the 1980s.

The financial crisis in 2008 led to a surge of bank failures, peaking at more than 150 in 2010. In this past year, failures have dropped to a level that can be counted with two hands.

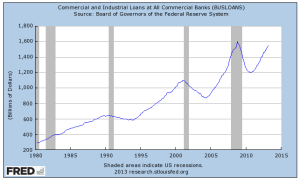

During the recession, the amount of commercial and industrial loans declined but have risen to nearly the same level as 2008.

From a thirty year perspective, we can see just how severe the decline was.

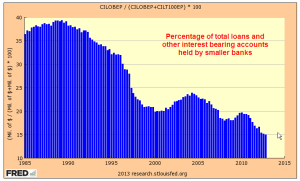

While loans and interest bearing accounts, or assets, at the largest banks are nearing 2007 levels, assets at small banks have declined.

The banking industry has been consolidating, larger banks eating up the smaller ones.

This past Friday, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, expressed concern that some of the larger banks are still prone to failure. The ever increasing size of the big banks has enabled them to have an even greater voice in the halls of Washington. Bernanke’s remarks hint that he is a proponent of further regulations which would reduce the amount of leverage that banks can use to increase their profits. Banking industry lobbyists are making the case that if they are required to reduce their leverage, it will hurt the economy by reducing the amount of loans they can make.

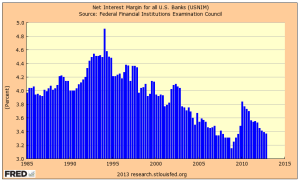

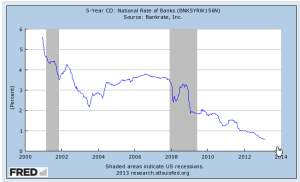

The banks are feeling squeezed and they are sure to let lawmakers know. Their net interest margin, or the spread between what they pay to depositors and what they charge to borrowers, has fallen to pre-recession levels, putting pressure on banks to take more risk to increase their bottom line.

I am reminded of a comment made by Raymond Baer, chairman of Swiss private bank Julius Baer, in 2009 who warned: “The world is creating the final big bubble. In five years’ time, we will pay the true price of this crisis.” Let’s see: 2009 + 5 = 2014. Hmmmm….

But we can’t live our lives waiting for the next catastrophe. We must take some risk, be diversified and be vigilant. As the stock market reaches new highs with each passing day, more investors will reassess their risk profile. Some will curse their caution of the past few years and move money from safe but low yielding assets to the market, helping to fuel rising market prices. The demand for yield creates a feedback loop that actually makes it harder to achieve yield. If only we could live in a world where they didn’t have these darn feedback loops.