February 4, 2024

by Stephen Stofka

This week’s letter is about the inflationary spurt that began a little over two years ago. The causes of the inflation have been a controversial topic among economists and political commentators. Some blame Biden and the Democrats for enacting a third round of stimulus shortly after he took office. That’s fiscal policy on the hot seat. Some target monetary policy, blaming the Fed for leaving interest rates at a pandemic low near 0%. In this letter, I will focus on a price signal that the Fed could have treated with more importance. A combination of the two is more credible. Republicans hope to make inflation and the immigration crisis at the southern border central issues in this year’s election campaign.

I’ll begin with two measures of changes in consumer prices. The Consumer Price Index, or CPI, is a headline gauge of inflation that reflects current price changes. Because Fed policy must anticipate price changes, it uses a a less volatile index called the PCEPI, or Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index. I’ll call it PCE. The CPI is based on a static basket of goods that the average family might buy each month. Households adapt to changing prices where they can but the CPI methodology does not measure that. Nor does it measure costs paid by someone other than the members of a household. To address those weaknesses, the PCE measures the actual spending choices that households make. The PCE includes expenses like health care benefits that an employer provides. The Cleveland branch of the Federal Reserve has a deeper dive on the differences between the two measures.

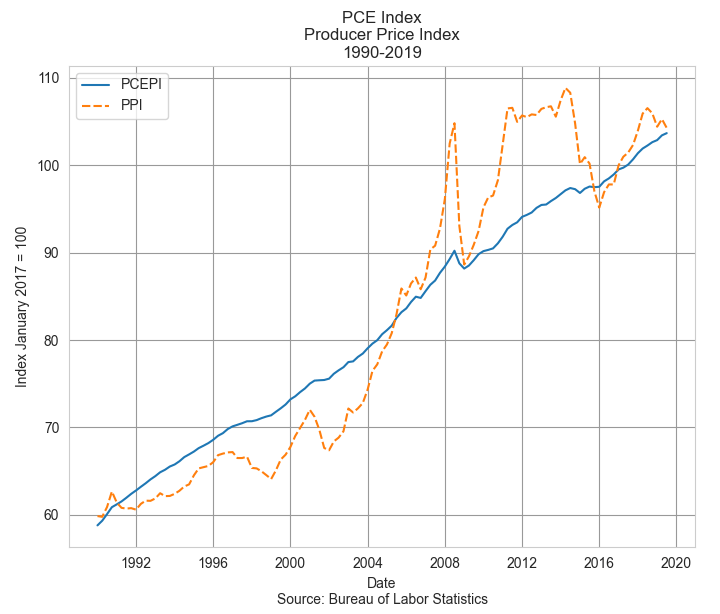

The oldest price index, first charted in 1902, is based on a measure of prices that producers and wholesalers receive at both the intermediate and final stages of production. In the final demand phase, a product is going to be sold to a consumer. In the intermediate stage a producer sells a product to another producer as a component in their product. Each month the BLS surveys thousands of companies to compile the wholesale prices on most of the goods sold in the U.S. and 70% of traded services. The agency then builds hundreds of indexes to measure the changes in those prices. The Producer Price Index, or PPI, is a headline composite of those indexes. As you can see in the graph below, the PPI is more volatile than the PCE measure of consumer price inflation. Government subsidies can increase the prices that suppliers receive with little impact on consumer prices. The PPI is more responsive to changes in transportation and distribution costs.

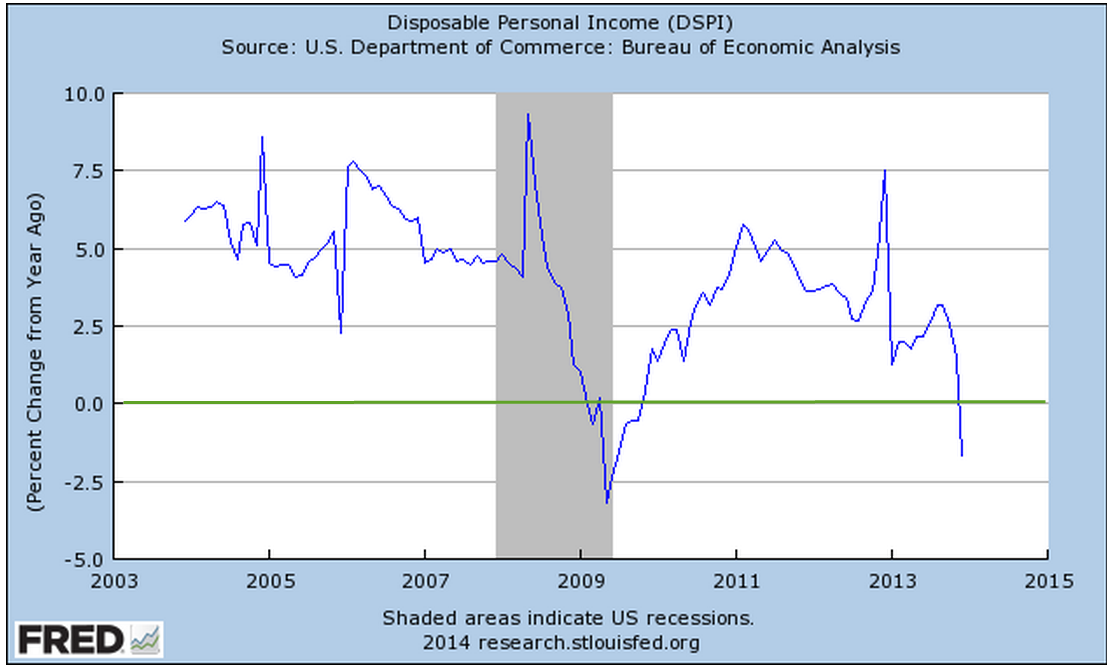

Despite its volatility, the PPI is regarded by the Fed, Congress and the administration as an advance indication of movements in consumer prices, according to the BLS. It indicates producers’ forecast of consumer demand and reflects economic stress and global supply pressures. However, wholesales prices may not be a reliable forecast tool of consumer inflation if the economy is weak and households cut back on their spending where they can. In the recovery years following the financial crisis in 2008, real GDP did not rise above 3% until the end of 2014. Unemployment finally dipped below 5% in the spring of 2016.

In 2021, the PPI indicated a developing surge in wholesale prices that would become apparent in consumer prices by the following year. But the economy still had not fully opened and unemployment did not fall below 5% until the fall of 2021. Would the pandemic recovery follow the sluggish trend of the recovery after the financial crisis? The Fed waited, preferring to keep interest rates low to support the labor market. In the graph below I’ve charted both the PCE and PPI over the past eight years. I’ve marked out the beginning of Biden’s term in the first quarter of 2021 and the Fed’s tightening that began in the spring of 2022.

The PPI (dotted orange line) had already reversed higher before Biden took office. As we can see in the chart above, the Fed did not enact stricter monetary policy until the PPI had peaked. In hindsight, the Fed was late to respond to surge in prices but Congress has given the Fed a dual mandate to maintain stable prices and full employment. During times of economic stress, those two objectives can indicate contradictory policies. During the initial months of the pandemic in 2020, five million people left the work force. In early 2020, the participation rate for the prime work force aged 25-54 stood at 83%. By the fourth quarter of 2021, the rate was still only 82%. 1.5 million workers had still not returned to the labor force. During a severe crisis like the pandemic, the Fed has trouble balancing those two objectives of stable prices and full employment. If they raised rates too soon, they could have damaged a recovery in the labor market.

While the general price level has come down in the past year, the inflation beast is not dead. There is still a residual inflation energy in some intermediate goods. Had the pre-pandemic price trends continued for the past four years, we might expect prices to be 8 to 10% higher than they were at the start of 2020. The prices of a number of goods have stabilized at levels far above their pre-pandemic levels. Meats are 32% higher after four years. Natural gas prices (WPU0551) have declined from the highs of last winter but are 38% higher than pre-pandemic prices. Residential electric power (WPU0541) and gasoline (WPU0571) are up 25% in four years. LPG gas is up 28% in that period. The prices of paper boxes (WPU095103) are up the same amount. Paper (WPU0913) is up 25%. The prices of bakery goods (WPU0211) are up 22% and still rising.

Despite promises made during the upcoming presidential campaign, the general price level is not going to return to its pre-pandemic level no matter who is president. The pandemic shook up the global economy, raised the general price level and there is no going back. A U.S. president may have their finger on the button of an arsenal of destruction but they have little influence on the producer prices of goods sold around the world. A hindsight analysis can identify policy winners and losers made by both the Trump and Biden administrations. The Fed and other central banks waited too long to respond to a worldwide inflation. Finally, the lessons learned from this pandemic will not all be applicable to the next global crisis.

////////////////

Photo by Ian Taylor on Unsplash

Keywords: PCE, PPI, wholesale prices, consumer prices, inflation

Note: In April 2022 the Fed began raising its key interest rate by .25% or more each month.