March 3, 2024

by Stephen Stofka

This week’s letter is about the federal government, its expenses and the role it plays in our lives. As originally designed in 1787, the federal government was to act as an arbiter between the states and provide for the common defense against both Indians and the colonial powers of England, France and Spain. James Madison and others considered a Bill of Rights unnecessary since the powers of Congress were clearly set forth in Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution. However, they agreed to attach those first ten amendments to the ratification of the Constitution to soften objections to a more powerful central government (Klarman, 2016, p. 594). After the Civil War, the federal government was given a more expanded role to protect citizens from the authoritarianism of the states. The authority to do so came from the amendments, particularly the recently ratified 13th, 14th and 15th additions to the Constitution (Epstein, 2014, p. 15).

After the Civil War, the Congress awarded pensions to Union soldiers, their widows, children and dependent parents. In 2008, there were still three Civil War dependents receiving pensions! (link below). This program indebted future generations for the sacrifices of a past generation. Aging soldiers sometimes married young women who would help take care of them in return for a lifetime pension until they remarried. The provision of revenues for these pensions provoked debate in Congress. In the decades after the Civil War, the federal government’s primary source of revenue was customs duties on manufactured goods and excise taxes on products like whiskey. Farmers and advocates for working families complained that this tax burden fell heaviest on them, according to an account at the National Archives. There were several attempts to enact an income tax, but these efforts ran afoul of the taxing provision in the Constitution and courts ruled them invalid. Fed up with progressive efforts to attach an income tax to legislation, conservatives in Congress proposed a 16th amendment to the Constitution, betting that the amendment would not win ratification by three-quarters of the states. Surprisingly, the amendment passed the ratification hurdle in 1913. In its initial implementation, the burden of the tax fell to the top 1% so many disregarded the danger of extending federal power. Filling out our income tax forms is a reminder that our daily lives are impacted by events 150 years in the past.

In the decade after the stock market crash of 1929, the government extended its reach across the generations. Under the Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) administration, the newly enacted Social Security program bound successive generations into a “pay-go” compact where those of working age paid taxes to support the pensions of older Americans. The government assumed a larger role in the economy to correct the imbalance of a free-market system which could not find a satisfying equilibrium. This expanded role of government and the writing of John Maynard Keynes (1936) helped spawn a new branch of economics called macroeconomics. This new discipline studied the economy as a whole and a new bureaucracy was born to measure national output and income.

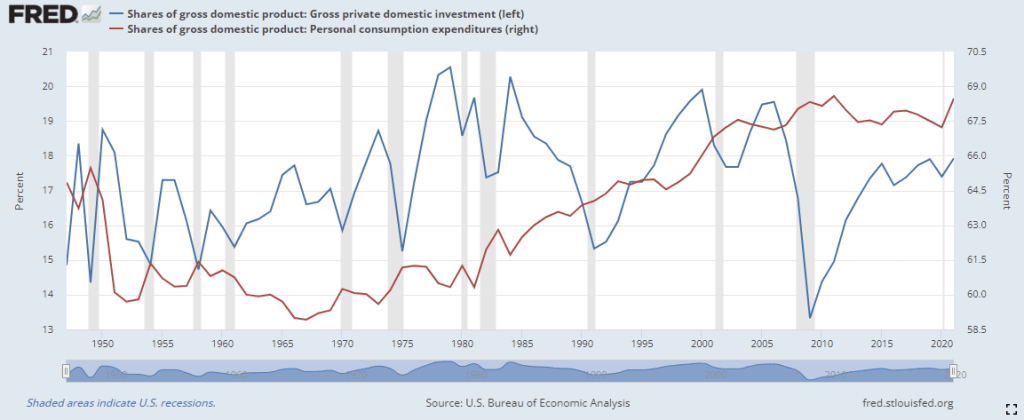

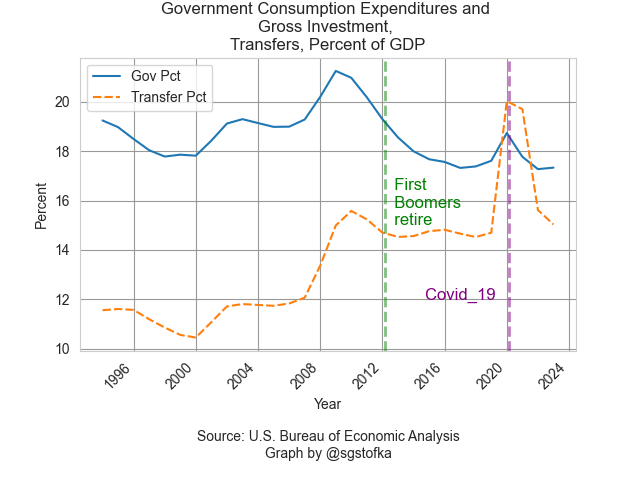

Students in macroeconomics learn that the four components of output, or GDP, are Consumption, Investment, Government Spending and Net Exports. In its simplest definitional form, GDP = C+I+G+NX. In the American economy each of these four components has a fixed portion of output. Net exports (FRED Series NETEXP) are a small share of the economy and are negative, meaning that America imports more goods and services than it exports. The largest share is consumption (PCE), averaging 67% over the past thirty years. Government spending and investment (GCE) and private investment (GPDI) have averaged an 18% share during that time. Because these two components have an equal share of the economy, more government spending and taxes will come at the expense of private investment. This helps explain the intense debates in Congress over federal spending and taxes. Federal investment includes the building of government facilities, military hardware, and scientific R&D. I have included a link to these series in the notes.

The Social Security program is as controversial as the pensions to Civil War veterans and their survivors. The long-term obligations of the Social Security program are underfunded so that the program cannot fully meet the promises made to future generations of seniors. The payments under this program are not counted as government spending because they are counted elsewhere, either in Consumption or Investment. They are treated as transfers because the federal government takes taxes from one taxpayer and gives them to another taxpayer. The taxpayer who pays the tax has less to spend on consumption or saving and the person who receives the tax has more to spend on consumption or saving. However, those transfer payments represent already committed tax revenues.

The chart below shows total transfer payments as a percent of GDP. Even though they are not counted in GDP, it gives a common divisor to measure the impact of those payments. The first boomers born in 1946 were entitled to full retirement benefits in 2012 at age 66. In the graph below those extra payments have raised the total amount of transfers to a new level. After the pandemic related relief transfers, total transfers are returning to this higher level of about 15% of GDP. I have again included government spending and investment on the chart to illustrate the impact that the federal government alone has on our daily lives. In one form or another, government policy at the federal level steers one-third of the money flows into the economy.

For decades, the large Boomer generation contributed more Social Security taxes than were paid out and the excess was put in a trust fund, allowing Congress to borrow from the fund and minimize the bond market distortions of government deficits. Outgoing payments first exceeded incoming taxes in 2021 and Congress has had to “pay back” the money it has borrowed these many years. To some it seems like a silly accounting exercise of the right pants pocket borrowing from the left pocket, but the accounting is true to the spirit of the Social Security program as an insurance program. Paul Fisher, undersecretary of the Treasury, quipped in 2002 that the US government had become “an insurance company with an army” but the quip underscores public expectations. Workers who have been paying Social Security taxes their entire working life expect the government to make good on its promises.

We are mortal beings who create long-lived governments that act as a compact between generations. We argue the terms and scope of that compact. What is the role of government? The founding generation debated the words to include in the Constitution and even after the words were on the page, they could not agree on what those words meant. The current generations are partners in that compact, still debating the meaning of the text of our laws and the role of government in our lives.

///////////////////

[20240303Government.jpg]

Photo by Samuel Schroth on Unsplash

Civil War pensions – a National Archives six page PDF https://www.archives.gov/files/calendar/genealogy-fair/2010/handouts/anatomy-pension-file.pdf

Data: a link to the four data series at FRED https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1hxIK. There is a small statistical discrepancy, and that series is SB0000081Q027SBEA.

Social Security: Notes on the adoption of a 75-year actuarial window used by the trustees of the Social Security funds to assess the ability of the program to meet its obligations. https://www.ssa.gov/history/reports/65council/65report.html. In 2021, the Congressional Research Service published a three-page PDF explainer for the choice of a 75-year term.

Epstein, Richard Allen. (2014). The classical liberal constitution: The uncertain quest for limited government. Harvard University Press.

Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment interest and money. Harcourt, Brace & World.

Klarman, M. J. (2016). The Framers’ Coup: The Making of the United States Constitution. Oxford University Press.