December 4, 2016

I’ve titled this week’s blog “The Un-Recovery Machine” for a reason I’ll explain toward the end of the blog as I look at the lack of growth in household income for the past 16 years. Lastly, I will show how easy peasy it is to do a year end portfolio review. First, I’ll look at the latest job figures and a quick five year summary of a few key stats of stewardship under the Obama administration.

The economy added 180,000 jobs in November, close to estimates. Obama will leave office with an average monthly gain of 206,000 jobs over the past five years, a strong track record. The president has a minor influence on the number of jobs created each month but each president is judged by job growth regardless. We need to have a donkey to pin the tail on when something goes wrong.

The real surprise this month was the drop of .3% in the unemployment rate to 4.6%. Some not so smart analysts attributed the drop to discouraged workers who dropped out of the labor force. However, the number of dropouts in November was the same as October when the unemployment rate declined only .1%. Seasonal factors, Christmas jobs and variations in survey data may have contributed to the discrepancy. What is clear is that the greatest number of those who are dropping out of the labor force are the increasing numbers of boomers who are retiring every month. I’ll look further at this in a moment.

The number of involuntary part-timers has dropped from 2.5 million five years ago to 1.9 million, about 1.3% of workers. This is a lower percentage than the 1970s, the 1980s, and the first half of the 1990s. It is only when the tech boom and housing bubble grew in the late 90s and 2000s that this percentage was lower.

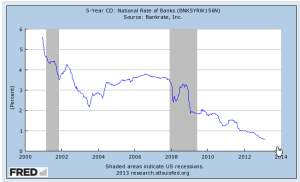

Growth in the core work force is a strong 1.5%, a good sign. These are the workers aged 25-54 who are building families, careers and businesses. The change in the Labor Market Conditions Index (LMCI) turned positive again in October. This is a composite labor index of twenty indicators that the Federal Reserve uses to judge the overall health of the labor market. They have not released November’s LMCI yet. This index showed negative growth for the first part of the year and was the chief reason why the Fed did not raise interest rates earlier this year.

The quit rate is back to pre-recession levels at a strong 2.1%. This is the number of employees who have voluntarily quit their jobs in the past month and is used to gauge the confidence of workers in finding another job quickly. The highest this reading has ever been was 2.6% just as the dot com boom was ending in 2001. Too much confidence. When the housing boom was frothing in the mid-2000s, the quit rate was typically 2.3%, a level of over-confidence. 2.1% seems strong without being too much.

Another unwelcome surprise this month was a .03 decline in the average hourly wage of private workers. On the heels of a welcome .11 increase in October, this decline was disappointing. One month’s increase or decrease of a few cents is statistical noise. The year-over-year increase gives the longer term trend. For the past five years, the yearly increase in wages has been unable to get above 2.5%, which was the annual growth in November.

The greatest challenge that the incoming president will face is the ever growing ranks of Boomers who are retiring. In 2007, the number of those Not in the Labor Force was 78 million. These are adults who can legally work but are not looking for work, and includes retirees, discouraged job applicants, women staying home with the kids, and those going to college. That number has now grown to 95 million, an increase of 2 million workers per year, and will only keep growing as the 80 million strong boomer generation continues to retire each month. The millenials, those aged 16 to 34, are a larger generation than the boomers but will not fully offset the number of retirees till the first half of the 2020s. If any president can explain this in very simple terms, it is Donald Trump, who has mastered the art of communicating a message in short bursts.

//////////////////////////

Construction and Local Employment

Construction employment matters. When growth in this one relatively small sector drops below the growth of all employment, that signals a weakness in the overall economy that indicates a good probability of recession within the year. It’s not an ironclad law like the 2nd law of thermodynamics but has proven to be a reliable rule of thumb for the past forty years. Fortunately, the economy is still showing healthy growth in construction employment that has outpaced broader job gains for the past four years.

The puzzle is why construction spending is an economic weathervane. It has fallen from 11% of GDP in the 1960s to slightly over 6% of GDP today. (Graph ) Yet when this relatively small part of the economy stops singing, there’s something amiss.

Real construction spending (in 2016 dollars) is currently at a healthy level of $175K per employee, 16% above the low of $151K in the spring of 2011. Although we have declined slightly in the past year, the average is about the same level as late 2006 – 2007 and is above the spending of the 1990s. As a rule of thumb in the construction industry, an employee is going to average 33% in wages and salaries. That doesn’t include the cost of employee benefits, insurance and taxes which will bring the total cost of the employee above 40% of the total cost. So, if spending is $175K, we can guesstimate that the average worker is making about $58K. When I check with the BLS, the average weekly earnings in construction is $1120, or almost $58K. As a side note: that 40% employee cost is used by some contractors as a rule of thumb for a bid total when estimating a job.

During the recession many workers dropped out of the trades. Older workers with beat up bodies cut back on hours, went on disability or took early retirement. Younger workers who saw the layoffs and lack of construction employment during the recession turned their sights to other fields. Workers who do come into the trades find that the physical transition takes some getting used to. Even workers in their twenties discover that muscles and joints working 8 – 10 hours a day need some time to adapt.

The average workweek hours for construction workers hit at a 70 year high in December 2015 and is still near those highs at 39.8 hrs a week. In some areas the lack of applicants for construction jobs is constraining growth. In Denver, construction jobs grew by almost 20% in the past year and that surge is helping to attract workers from other states. The unemployment rate in Denver is 2.9%, below the 3.5% in the entire state. (BLS Denver Colorado) This pattern is not confined to Colorado. Very often economic growth may be strong in the cities but weak and faltering in rural communities throughout the state. For decades this has caused some resentment in rural communities who feel that politicians in the cities dominate policy making in each state.

Local employment

The Civilian Labor Force, those working and actively wanting work, is growing in all states except Alaska, Louisiana, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Nebraska, Nevada, Oklahoma and Wyoming (BLS here if you want to look up your city or state stats). Some of the changes may be demographic. I suspect that is the case in New York and New Jersey. The decline in some states are those related to resource extraction. Employment in states with coal mining and oil production has taken a hit in the past two years. In Colorado, the 11% gain in construction jobs has offset a 12% decrease in mining jobs.

/////////////////////////////

Household Income

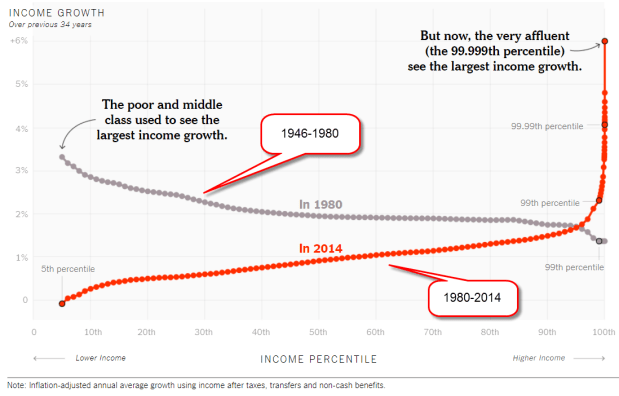

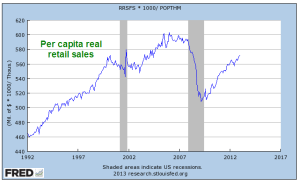

On a more sobering note…In 1999 real median household income touched a high $58,000 annually. Sixteen years later that median was $56,500, a decline of about 3%. There’s a lot of pain out there.

For readers unfamiliar with the terminology, “real” means inflation adjusted. “Median” is the halfway point. Half of all incomes are above the median, half below. Economists and market analysts prefer to use the median as a measure of both incomes and house prices to avoid having a small number of large incomes or expensive houses give an inaccurate picture of the data.

Both parties can take responsibility for this – two Republican administrations (Bush) and two Democratic (Obama) terms. There have been a number of different party configurations in the Presidency, House and Senate, so neither party can reasonably lay the blame at the other party’s feet. The “new” more idealogically pure Republicans in the House regard the “old” Republicans of the two Bush terms as traitors to conservative ideals. Never mind that a lot of those “old” silly Republicans are still taking up room in the House.

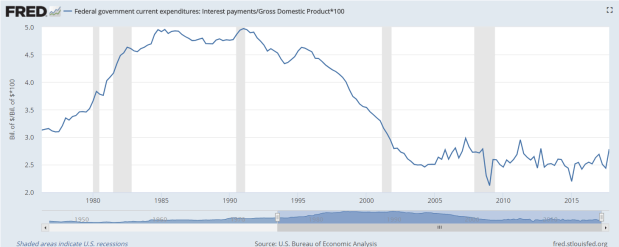

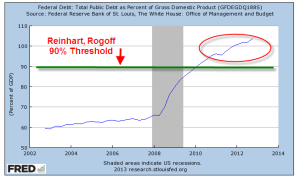

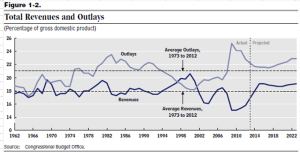

Both parties have borrowed and spent a lot of money but little has flowed down to the American worker. So much for the imaginativeness of trickle down economic theory. When George Bush assumed office in January 2001, the Federal Public debt totalled $5.6 trillion. When he left office in January 2009, the debt had almost doubled to $10.7 trillion. Under Obama’s two terms, the debt nearly doubled again, crossing the $19.4 trillion mark in June 2016. $14 trillion dollars of Federal borrowing and spending since early 2001 has not helped lift the incomes of American families. It is a damning indictment of both major parties who have lost touch with the everyday concerns of many American families.

Can Donald Trump be the catalyst that miraculously turns the Washington whirlpool of money into an effective machine? Doubtful, but let’s stay hopeful. 535 Congressmen and Senators, each with an outlook, a constituency, and an agenda funded by a coalition of lobbyists, are going to fight against giving up control. Spend the money on my constituents. they will say. Republicans throw out the phrase “limited government” to their base voters who whuff, whuff and chow down. Once elected, many Republican politicians are as controlling as their Democratic counterparts, only in different areas of our lives. A Republican controlled government will push for more regulations on women’s health, regulations on people’s moral and social behaviors, a proposal to reinstitute the draft, and threats to private companies who move jobs out of the U.S. Donald Trump recently enacted Bernie Sanders’ prescription for keeping jobs in America. He no doubt threatened Carrier’s parent corporation, United Technologies, that they would lose defense contracts if Carrier moved all those 1000 jobs to Mexico.

So Donald Trump, the leader of the Republican Party, is following a socialist play book. We are going to see more of this because Trump is the leader of the Trump party, not wedded to any particular ideology. He is a transactional leader who plays any card in the deck to win, regardless of suit. Chaining oneself to ideals is a good way to drown in the political soup.

Republicans in Washington have consistently betrayed conservative ideals of financial responsibility and a smaller government imprint on the daily lives of the American people. Democratic politicians cluck, cluck about progressive principles but Democratic voters find that their leaders have left them a pile of chicken poop. Unlike Republican voters, Democrats haven’t developed the organizational skills to make personnel changes in party primaries. Both parties are infected with old ideas, loyalties and prejudices.

Because of this, retail investors – plain old folks saving for their retirement – can expect increased volatility in the next two years. We may look back with fondness at these last two years, a peaceful time of few accomplishments in Washington, and a sideways market in stocks and bonds. A balanced portfolio will help weather the volatility.

Mutual fund companies and investment brokers track this information for us and we can access it fairly easily online at the company’s website. Even if we have several places where we keep our funds, it is a relatively simple paper and pencil process to calculate our total allotment to various investments. We don’t need to be precise. We are not launching a rocket to Mars.

If I have $198,192.15 at Merry Mutual and they say I have 70% stocks and 30% bonds, I can write down $140 in stocks, $60 in bonds. Then over to my 401K at the Ready Retirement Company to find out that I have $201,323.39 balance, with 80% stocks and real estate funds and 20% bonds. I write down $160 for stocks and $40 for bonds. Then over to my savings account at Safety Savings where I have $39,178.64, which I include with my bonds. I write down $40. Finally, over to my CDs at the First Best Bank in my neighborhood where I have $32,378.14 in CDs of various maturities. I include those with my bonds and write down $32. Maybe I have an insurance policy with some paid up value that I want to include in my bonds.

So, adding it all up, my stocks (more risk) are $140 + $160 = $300. My bonds/cash (less risk) are $60 + $40 + $40 + $32 = $172. $300 + $172 = $472 total portfolio value. $300 stocks / $472 total = .635 which is about 64%. So I have a 64% / 36% stock / bond split and I have figured this out without expensive software, or an investment advisor.

Depending on my comfort level, knowledge and expertise I may want some software or some advice from a professional but I know where my allocation lies. I am on the risky side of a perfectly balanced (50% / 50%) portfolio and how do I feel about that? If I do talk to an advisor or a friend I can tell them up front what my allocation is and we will have a much more informed conversation.