March 10, 2019

by Steve Stofka

Many Americans cross the street if they think a socialist program is walking toward them. We believe that the U.S.A. is the heart of capitalism, but recent history reveals that our financial and legal systems are based on socialism for the very, very rich.

In the past two weeks, I reviewed the infrastructure goals as well as the justice and education goals of the Green New Deal (Note #1). In Part Three this week, I’ll look at the income supports included in the resolution’s economic agenda.

“Guaranteeing a job with a family-sustaining wage.” This is yet another example of clumsy language used to state a goal that some might read as utopian. Some can group the first phrase as ” Guaranteeing a job with a family sustaining wage” meaning that all wages should have a certain minimum. That sounds like the language of Minimum Wage 2.0, but does that mean that each job should be able to support a family of four, or six, or eight?

Others might group the first phrase as “Guaranteeing a job blah, blah, blah” and read the intent as a platform point of a Socialist Manifesto. Is the government going to hand out jobs to everyone that wants one? Only if the government takes over some of the means of production and becomes the nation’s chief employer can it hand out jobs to anyone who wants one. That is the textbook definition of socialism. It is not enough to have good intentions. Clarity of language matters.

Why the clamor for more income redistribution? The real (after inflation) income of poor and working families has lost more than half since 1980. That might not surprise some readers. The trend is even broader and more insidious. Income data from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) shows that even the top 5% of real incomes have dropped 30%. The real income of a ¼ million families – the very, very rich – have grown in that time. Here are some highlights from the data.

In 2015 and 1980, the number of poor households, or bottom 20%, equaled the number of rich households, or top 20%. In 2015, the government took money from each rich household and gave it to 5-1/4 poor households to raise their income by 65% (Note #2). In 1980, the government took money from each rich household and gave it to 10-1/4 households to raise their income by only 25% (Note #3).

Why did poor households need so much more support in 2015 than they did in 1980? Because their real incomes before transfers and taxes (BTT) lost more than 50% (Note #4). The real BTT incomes of the top 5%, the very rich, have lost more than 30% . It is only the very, very rich, the top 1%, that have fared well in this fight against inflation. Their BTT income has grown 15% in the past 35 years. The bulk of those gains have probably come from the top .1%, or less than ¼ million families.

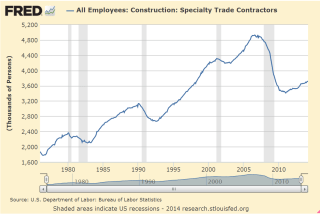

Why? Where has the money gone? The high interest rates of the 1980s made the dollar so strong that manufacturers began to move their operations to lower cost markets in Asia. Japan kept the value of the yen low relative to the dollar and attracted much of this investment. The Japanese economy and real estate boomed. American exports of manufactured goods declined, and commodity prices crashed, destroying a lot of income producing wealth, particularly in rural areas (Note #5). Bankruptcies during this decade far exceeded those filed during the Financial Crisis ten years ago (Note #6). Older readers may remember the charity concerts to raise money for farmers (Note #7). Today, many commercial buildings in small towns throughout the country stand empty. As rural clinics and nursing homes close, people must move to urban areas where medical services are available (Note #8).

As real incomes declined in the late 1980s, households and governments borrowed to make up for the loss of income. Who did they borrow from? Financial institutions who managed the assets of the very, very rich. As the financial sector grew in proportion to the size of the entire economy, the top managers of financial firms became very, very rich themselves (Note #9).

In the past twenty years, lobbying by the financial sector has quadrupled (Note #10). It paid big dividends during the latest crisis. After the initial bailout by the Bush administration in the fall of 2008, the Obama administration brought in a team led by Robert Rubin, Larry Summers, and Timothy Geithner. The first two helped dismantle the safeguards between deposit banks and investment institutions during the Clinton administration. Geithner was a protégé of Rubin. All were deeply embedded in the interests of the banks, not the creditors and governments who had trusted the judgment of financial managers.

The lack of separation between deposit banks and investment banks helped spread a cancer from the investment banks to banking institutions throughout the world. As Obama’s Treasury Secretary, Geithner continued to protect the bonuses of top managers despite massive losses. To preserve the wealth of the very, very rich, the Federal Reserve loaded up their own balance sheet with toxic bonds bought at full value.

After a 35-year period of rising real incomes and wealth because of favorable fiscal and monetary policy in Washington –

after Washington protected their wealth and income during the financial crisis at the expense of middle-class families who lost their savings and houses –

it is time for the very, very rich to pay taxpayers back.

You have eaten well. Here is the check.

//////////////////

Notes:

1. Politifact article

2. In 2015, the bottom 20% of households (24.3 million) averaged $20,000 in income before taxes and transfer payments. The top 20% (25 million) earned almost $300,000. After taxes and transfer payments, the incomes of the bottom 20% rose 65% to $33,000. CBO report on household income in 2015, updated Nov. 2018

3. Number of households underlying CBO report is in Sheet “1. Demographics” of Supplemental Data spreadsheet linked on last page of report. Dollar amounts are in Sheet “3. Avg HH Income”, of same spreadsheet.

4. The impact of high interest rates on investment and commodities during the 1980s Secrets of the Temple pp.590-604

5. Using BLS calculator to compare CPI January 1980 to January 2016 prices, $1 in 1980 = $3.05 at the end of 2015. Average income amounts from Sheet 3. See Note #3 above.

6. Four decades of bankruptcies chart at Trading Economics

7. Farm aid timeline

8. Nursing centers in rural areas are closing NYT

9. The financial industry’s increasing share of GDP

10. Increase in financial lobbying since 1998