May 8, 2022

by Stephen Stofka

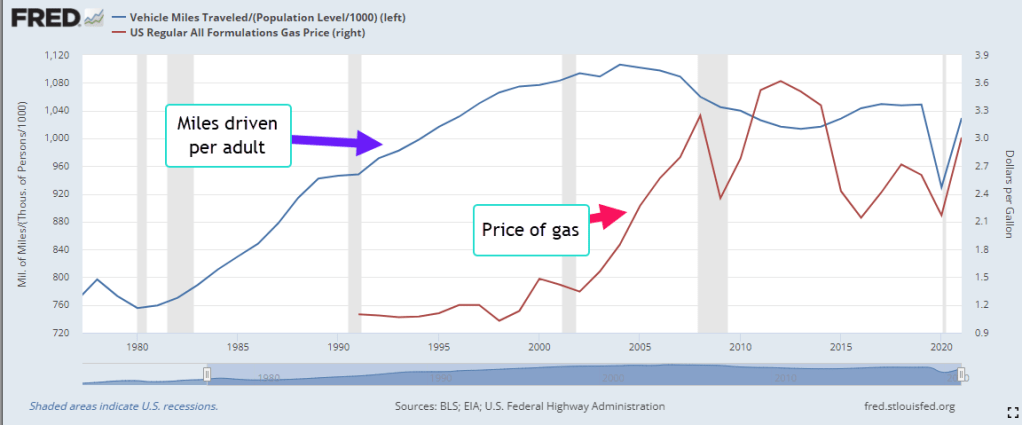

A second round of the pandemic in key areas of China, continuing bottlenecks at ports and the war in Ukraine have played a key part in the persistence of inflation over the past few months. Supply shocks give companies a chance to raise prices faster than their production costs and increase profits – at first. This gives companies a chance to make up for lost profits during the pandemic. The rise in costs will hurt eventually and companies will blame rising wages.

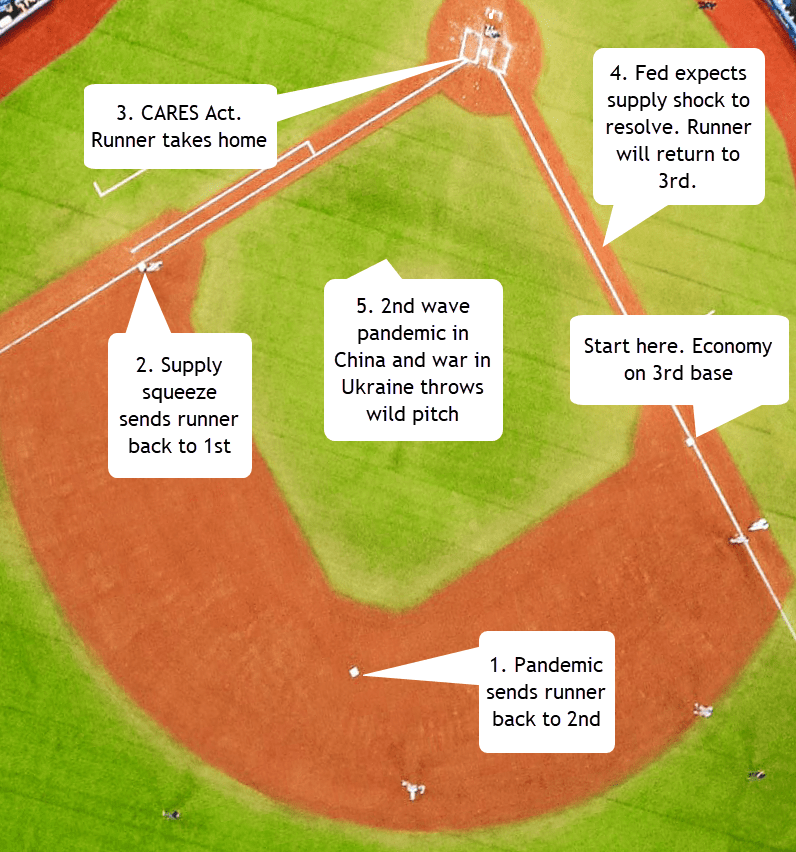

Some people are blaming the Fed, accusing them of being behind the curve. I’ll present a model that helps readers understand the sequence of events over the past two years. Economists study how events, people and money interact. Like a football coach drawing out a strategy for a defensive backfield, economists use graphs with diagrams of solid and dashed lines with arrows to describe the dynamics of a process. For the layperson, it can be confusing. To make it fun, I sketched the dynamics on a baseball field. The action starts in the spring of 2020 with the runner – the economy – on 3rd base. Governments around the world dampened or shut down their economies to arrest the spread of the Covid-19 virus. I’ll put the graphic up here. Economists will recognize the bases as equilibrium points, and the left and right shifts of demand and supply.

The pandemic sent the runner to 2nd base, a shift of demand. Supply constraints then sent the economy back to 1st base, a shift of supply. The CARES act and other government support programs could only send the runner to home, a shift of demand. Why not back to 2nd? Let’s keep it simple and say that those are the rules. The Fed’s monetary policy has already consisted of large measures in response to the pandemic. That is on another graph with DD and AA curves that would give a casual reader a headache.

The Fed knew that the economy should be on 3rd – not home base – but expected the supply constraints to resolve enough to shift the economy back to 3rd base. If the Fed took monetary action when it was not needed, the runner might get injured and have to rest. That’s a recession. So the Fed waited, ready to take action if the existing supply chain problems didn’t resolve.

Another wave of pandemic struck key manufacturing areas in China. In the U.S., ports on the west coast and transportation links to those ports were still not working properly. Russia attacked Ukraine, driving up the price of gasoline by more than 50%. Natural gas prices rose 160% (DHHNGSP https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=P3jr ). As the war continued for several weeks, it became clear that there would be no spring planting of crops in Ukraine, a country that is a global food supplier. Futures prices rose, increasing grocery store prices and exacerbating the sharp rise in oil prices.

The Covid-19 virus, the many people and businesses in the supply chain, and Vladimir Putin did not pay attention to the informed expectations of the Federal Reserve. The Fed is a convenient target for pundits. Before the Fed was created in 1913, people blamed gold and anonymous speculators for panics and price instability. However, anonymous speculators do not show up for Congressional committees. A bar of gold just sits silent in the chair while committee representatives rant on at finance hearings. That’s no fun. The Fed has a chairperson, Jerome Powell, a punching bag for Congress and pundits. Taking verbal abuse is part of the job of being Fed Chair.

Congressional representatives often use charts in the main chamber. An aide slides a cardboard chart on an easel while the Congressperson explains the whole idea in 5 minutes. At a finance subcommittee hearing, Mr. Powell can bring in an easel with a diagram of a baseball field. He can point to the economy on 3rd base and explain the whole process in a simple but more eloquent way than I can. Once the committee members understood the idea, they would apologize to Mr. Powell for their earlier criticism and Washington would be a more peaceful place. If baseball players and managers could resolve their differences this spring, why can’t the folks in Washington? Play ball and a shout out to moms everywhere!

////////

Photo by petr sidorov on Unsplash