August 13, 2016

What is inflation? Commonly regarded as the change in prices from one year to the next, we can also define it as the rate at which the value of money declines. In classical monetary theory, inflation reflects government demand for private savings. When savings can not meet the demand, immoderate governments create the money they need. This influx of invented money leads to higher prices and inflation.

Higher inflation encourages borrowers, including governments, since they can pay back loans borrowed in Year 1 with money that is worth less in Year 2. A person who borrows $100 for a year at 10% interest but with 10% inflation, pays back a total of $110. But the $110 is only worth 90%, or $99, in purchasing power. In effect, the lender has paid the borrower for loaning the borrower money. In a case like this, no one wants to lend money at that interest rate. The lender must charge a higher interest rate, driving up the price of borrowed money in a self-reinforcing tailspin of inflation chasing interest rates chasing inflation.

Deflation, or negative inflation, discourages borrowing for the opposite reason; money borrowed in Year 1 is paid back with money that is worth more in Year 2. That same $100 borrowed for a year at 10% interest and 10% de-flation is paid back with $110 that now has the purchasing power of $121. In this example, the borrower effectively pays the lender 21% interest.

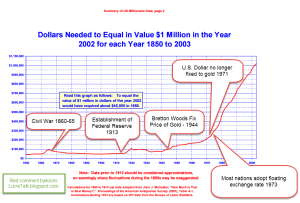

I marked up a graph of post-1850 inflation I found here to show several key points in the “hockey stick” of inflation.

The Federal Government borrowed and spent a great deal of money during the Civil War period 1860-65, driving up the rate of inflation. With a currency backed by gold and sometimes silver, it took several decades of intermittent deflationary periods to correct for the imbalance of the Civil War.

When the Federal Reserve was created in 1913, the value of a dollar was little changed since 1850. The Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t compile data on inflation before 1913. After a World War and a severe short recession, a dollar in 1920 was worth half of what it was in 1913 {BLS }

Several years of deflation after the stock market crash restored some of the value to the dollar until the Federal Government began borrowing large sums of money to fund Roosevelt’s New Deal. Inflation accelerated under the heavy government borrowing for World War 2.

Even though Roosevelt had ended the ready convertibility of dollars to gold during the Depression, several countries wanted cooperation in setting an international monetary standard. At the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, a year before the end of World War 2, the price of gold was fixed at $35 per ounce, a dollar benchmark that effectively made the U.S. dollar the world’s reserve currency.

In 1971, the Nixon administration removed that fixed price and allowed the dollar to float in price against gold and other currencies. Within two years, the rest of the developed world followed suit. A glance at the chart shows that this is the bend in the hockey stick, the point where cumulative inflation marches relentlessly upwards.

As I noted at the start, some inflation encourages borrowing. The keyword is “some.” High inflation introduces so much uncertainty into the economy that it becomes debilitating. Workers can not negotiate wage increases fast enough to keep up with the speed of inflation,, so they reduce their real spending. Lenders demand high interest rates when they lend money in order to compensate for the declining value of money. The high rates discourage borrowing and crimp economic activity.

A reasonable and fairly predictable inflation rate allows debt burdened governments to pay back borrowed money with money that has less value. In half a lifetime, from the point in 1973 when most governments freed their currency from a gold standard, the U.S. dollar has lost 80% of its value. For the first two decades of these past forty years, family income kept pace with that loss of value. During the last two decades the value of a family’s labor has been transferred to governments whose elected officials devise programs to return some of that transferred value to the most disadvantaged families.

In real terms, personal incomes have more than tripled since 1973 {Graph} but most of those gains were in the twenty-five years ending in 2000 when real personal incomes grew by 135%, a 5% annual pace. In the sixteen years since 2000, real incomes have risen only 35%, averaging slightly above 2% per year. When the value of money declines, the only way to save value is to invest money in assets, and only those on the upper half of the income scale have been able to preserve the value of their money in assets. The lower half on that income scale has struggled.

As the value of money has declined in the past forty years, money invested in assets have gained in value. The press goes goo-goo as the SP500 makes new highs but that is a nominal value. The inflation adjusted value is barely above its value in 2000 (Table) but has tripled in real value since 1973. Home prices have not done as well but have gained 50% since 1975 (Graph). For many families, their house is the majority of their assets and the inflation adjusted Case Shiller home price index is still below the level of ten years ago.

Elections are a competition of ideas for solutions and this election is no different. The chief theme has been the ever declining value of money and labor, the relentless struggle of those on the lower half of the income scale. Folks on the political left favor ever more government intervention and clamor for more social programs to reduce household expenses, including free college tuition, childcare and medical care. On the income side, the left calls for a doubling of the minimum wage. Higher taxes and more debt will pay for these solutions.

Folks on the right side of the political aisle are ruled by an ideology that opposes government solutions, believing that there always exist remedies from the private sector even if there are no proposals for a private solution. However, even those on the right want more government spending, but of the military kind, where it can most benefit families and economies in rural communities. Donald Trump is now calling for greater infrastructure spending but this is sure to anger the conservatives in his party. Folks on the right claim that more spending will be paid for by lower taxes on upper income families and the magic of wishful thinking called optimistic economic assumptions and dynamic budget scoring

For more than four decades, the world has been engaged in an international game of currency manipulation to prevent the fair market pricing of each country’s currency. Nations newly industrializing disregarded or gave a knowing wink to international agreements on labor practices and environmental protections. Now the populations of the developed countries are aging and their birth rates are falling, particularly those countries in western Europe. Already high government debt levels are strained by a swell of retiring workers who want the pension benefits they have been promised. Economic growth that is sluggish or non-existent can not meet the demands for services and benefits, prompting more government borrowing.

Promises in a Presidential campaign are like unicorns. After the election, the candidate removes the horn and voters realize that what they got was a rather good looking but ordinary horse, not a magical unicorn. Promises are nevertheless calling cards to a political vision, and the vision of both campaigns is a rally ’round the flag of the domestic economy and American families. Trump’s supporters are endorsing his call for tariffs on imported goods to punish those countries which subsidize their industries and make American products less competitive in price. Hillary Clinton is now calling for penalties for company inversions, the practice of relocating the legal presence of a business overseas to lower a company’s tax liability. To rally their troops each candidate promises to fight the international system that threatens the well being of many American families. However, it is our own government that is part of that system, the war on the value of money, on the value of work.