February 23, 2025

by Stephen Stofka

This is second in a series on centralized power. I decided to use a more conventional narrative rather than the debate format of previous posts. Research on this topic upset my “apple cart” of preconceptions regarding spending, taxes, and Republican support for some social programs. I survived.

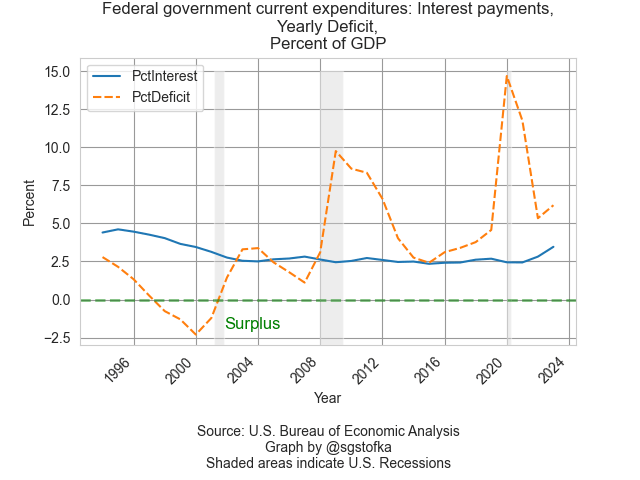

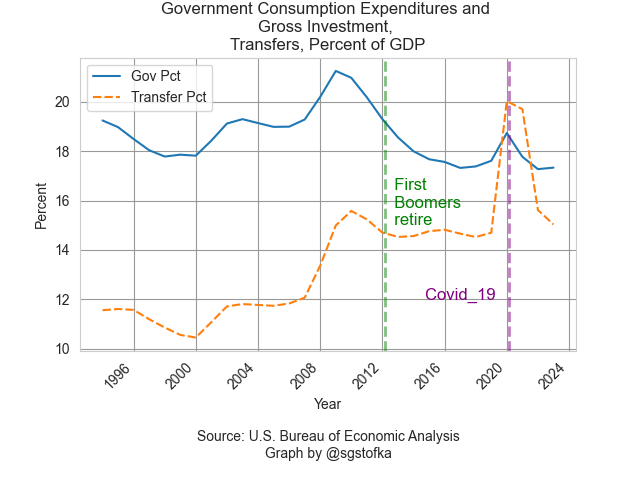

Proponents of smaller government aim to restrain the growth of government spending by reducing tax revenue. In a 1981 Address to the Nation shortly after taking office, President Ronald Reagan first proposed the idea. If Congress would not cut back spending, then reducing tax revenues would force them to cut spending. As many political leaders did, Reagan assumed that the public would not tolerate the nation running large fiscal deficits. For most of the eight years he was in office, government spending stayed fairly constant at about 22% of GDP and the federal deficit remained at the same percent of GDP as during Jimmy Carter’s term. After 9-11, the public’s tolerance for deficits grew. The feckless Bush administration promised that Iraqi oil production would pay for the costs of invading the country. In 2003, the Republican Congress passed tax cuts and Bush won reelection despite the many failures of the Iraqi invasion. This time, he did so without the help of the conservative justices on the Supreme Court. It was the last time a Republican would win the popular vote until the election of Donald Trump in 2024.

A 2006 analysis by Christina and David Romer found little support for the Starve the Beast hypothesis and suggested that lowering taxes may, in fact, increase spending. In a 2006 paper, William Niskanen, former head of the Cato Institute, found that spending and tax revenues moved in opposite directions. One of the pathways for this phenomenon may be that taxpayers come to disconnect the two forces, taxes and spending, and don’t hold politicians responsible. For a politician, cutting taxes is a popular brand but they keep their seats by “bringing home the bacon” for their constituents. A farming community does not want to see decreases in crop subsidies or favorable tax breaks. Voters magnify the burden of spending cuts, feeling as though they are shouldering more of the burden than other voter groups.

In his second term, Donald Trump has adopted a different approach – kill the beast. Readers of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies will remember the scene where a mob mentality overtakes a group of shipwrecked boys and they start a feverish chant after a hunt, “Kill the pig, spill its blood.” The cuts that Musk and his DOGE team are making on the federal work force resemble less the precision of a surgeon and more the frantic swinging of a knife in the dark. They have targeted recent hires with few job protections and paid little attention to what those workers do. In their zeal to kill or wound the bloated government – the beast – they have laid off nuclear safety and food safety workers, infectious disease specialists and IRS workers near the height of tax filing season. Both Musk and Trump are among the wealthy elite. Neither is dependent on a tax refund.

In his recently published book Why Nothing Works: Who Killed Progress—and How to Bring It Back, Marc J. Dunkelman recounts the expansion of the federal government, starting with the Progressive movement that began under Theodore Roosevelt’s administration over a hundred years ago. The movement embodies two instincts that are in constant tension, a “progressive schism” whose roots began when the nation was founded (pg. 22). Alexander Hamilton favored a strong central government whose institutions could facilitate the commerce and defense of the new American republic. Thomas Jefferson believed that the integrity and character of the new nation depended on the yeoman farmer, who must be protected from the power of government. Jefferson was horrified by the abuses of a strong British government headed by a monarch.

Progressives want to expand the reach of government – the Hamiltonian instinct – but are fearful of the power of government – the Jeffersonian instinct. The struggle between these two sentiments frustrates the aims of the Progressive movement. Progressives’ “cultural aversion to power renders government incompetent, and incompetent government undermines progressivism’s political appeal” (pg. 15).

For more than a century conservatives in both political parties have tried to check the ambitions of the progressives and the expansion of the federal government. For almost a century following the civil war, southern Democrats fought to preserve their political dominance and cultural institutions from the imposition of reformist norms by “northern elites.” There is still a strong antipathy to federal power but most of us have adapted to and enjoy federal institutions created by progressive legislation. Millions of Americans enjoy our national parks and monuments but over a century ago, local groups protested federal interference in the management of lands within state boundaries like Yellowstone Park, Glacier National Park and Grand Canyon National Park.

We no longer argue over child labor laws introduced by progressives in the early 20th century. Though popular today, conservative groups fought against the Social Security program when it was first introduced in the 1930s. Congressional Republicans, however, were largely unopposed, according to this 1966 interview with George Bigge. Opposition to “socialized medicine” stymied proponents of a Medicare type system first proposed in 1942. In the 1950s, President Eisenhower initially supported a health plan financed through the Social Security system but dropped his endorsement over objections that the program was a slippery slope to socialized medicine (Source). Wilbur Mills, the powerful Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, overcame Republican opposition to the Medicare program by introducing a Part B system for physician payments that would be voluntary. Many of us make an uneasy truce with federal power when those policies produce a net gain for our well-being, or there are limits to federal mandates.

This week, Donald Trump completed the first month of his second presidential term with a whirlwind of federal job cuts and controversial remarks. The first ninety days of a presidential term are said to be the honeymoon period when public opinion is still forming but recent polls by Quinnipiac University and CNN indicate that initial favorable sentiment has soured. More respondents disapprove of Trump’s policies than approve. Trump has promised to downsize both spending and taxes but preserve the Social Security and Medicare programs. Both programs are popular, as many voters feel that people have earned the benefits after a lifetime of paying taxes. The taxes, or dues, come first; the benefits come later.

There are no dues for the Medicaid program which provides health care insurance for low-income households. The federal government and states share the costs of this program in varying degrees, with the federal government picking up the majority of the costs. The Republican majority in the House has proposed $880 billion in cuts to the Medicaid program and Trump has expressed support for the cuts, surprising some Republican lawmakers and Trump’s own staff.

Trump acts with the impulsiveness of a 14-year-old boy. In an earlier age, the public wanted a stable hand in control of a vast nuclear arsenal. Thirty years after the end of the Cold War, voters seemed less concerned with Trump’s erratic behavior. Some excuse it as a negotiating ploy; others see it as a tactical maneuver. In Washington, where everyone has a “loaded weapon,” so to speak, Trump presents a moving target. Others see the policy moves as sheer incompetence. Over a thousand employees at the National Park Service were laid off and seasonal hiring was frozen (Source). Oops. Seasonal employees fight forest fires and clean bathrooms at National Parks. The Trump administration did an about face and promised to hire even more seasonal employees than the Biden administration did (Source). The daily two-step is a boon for news organizations and pundits. Lots of copy. Not a dull moment in the 24-hour news cycle.

Advocates may clamor for the death of the beast – the government – but many of the functions that the beast provides are popular. In 1963, the folk group Peter, Paul and Mary released the song Puff, the Magic Dragon. Although Puff was an eternal creature, his friend Jackie Paper eventually lost interest in Puff as he grew up. After his friend abandoned him, Puff lost all his vigor and retreated into his cave by the sea. Some wish that the federal government would do the same. Lobbyist Grover Norquist wished that government would become so small that “we can drown it in a bathtub” (Source). Unlike Jackie Paper, the majority of the public has not outgrown its affection for government programs or its belief in the magic of government power.

//////////////////

Image by ChatGPT at the suggestion “draw a picture of a multi-colored dragon on the shore of the ocean with a cliff behind him.”