June 22, 2025

By Stephen Stofka

Sunday morning and another breakfast with the boys as they discuss world events and persistent problems. The conversations are voiced by Abel, a Wilsonian with a faith that government can ameliorate social and economic injustices to improve society’s welfare, and Cain, who believes that individual autonomy, the free market and the price system promote the greatest good.

Cain twirled the rod on the blinds to reduce the sunlight. “Boy, it’s hot this week.”

Abel said, “I can take that side if you want. Nice and shady on this side.”

Cain replied, “Nah, it’s ok. There we go. That’s better. Anyway, did you hear about the Supreme Court’s decision this week? They said that states can pass laws that make it illegal for doctors to prescribe puberty blockers to minors (Source). I thought you would be up in arms about that.”

Abel replied, “I’m not. I thought it was a reach, especially with this conservative court. The plaintiffs in the case wanted to blur the distinction between gender and sex so that they could claim sex discrimination under the Fourteenth Amendment. The Biden administration filed an amicus brief in the case. Come on, Joe. You’re supposed to be a middle of the road guy. You were captured by the progressive wing of your party.”

Cain laughed. “Criticizing Biden? I thought it was performance politics, not legal reasoning. The Trump administration reversed their amicus argument as soon he was elected.”

Abel looked around the restaurant. “Where’s the guy with the coffee and water? Anyway, the N.Y. Times had a magazine article on the history of the case (Source). Ok, there he is.”

Cain settled back in his seat as the busser poured coffee for each of them. “It’s a tough job,” he said. “I bused for a country club when I was like 16 or so. Summer job. Everyone wants to be served as soon as they walk in the door. Anyway, have you heard of WPATH?”

Abel asked, “No. Sounds like a public transportation thing.”

Cain chuckled as he spelled out the acronym. “It’s some psychiatric association for transgender care that issued guidelines for treatment of transgender people in 1979.”

Abel frowned. “That long ago? It seems like its only in the past ten years or so that this has become an issue. Shows how long these things take to come to general attention. So what’s the deal with WPATH?”

Cain replied, “So this professional association revised its guidelines in the late 1990s to ‘permit’ not ‘recommend’ puberty blockers for minors in rare cases. So, get that. Rare cases only. And it was only for minors aged 16 or over. Then in 2012, they relaxed their guidelines to permit treatment in minors under age 16 (Source).”

Abel interrupted, “Maybe that’s why this issue has only come to the public’s attention in the past decade. Ok, so go on.”

Cain said, “In 2022, get this, they revised their guidelines again to ‘endorse,’ not just permit, puberty blockers starting at puberty.”

Abel smirked. “Ah, the step too far.”

Cain nodded. “Exactly. First the policy permitted sex-hormones in rare cases for emotionally disturbed individuals who were almost legal adults. Now it has grown into a recommended procedure for a lot of children who might be only 11 or 12 years old. Some states said no. A state often acts as a surrogate for parental responsibility like at school. It has a right to exercise reasonable prudence.”

Abel smiled when Maria appeared at their table. “Hello, boys. What will it be? The same as usual? Number one over medium, rye toast, and number four with French toast and bacon?”

Abel replied, “How many customers do you have memorized? Absolutely genius. Anyway, can I switch to sausage this week?”

After Maria left with their order, Abel said, “I think they changed their bacon supplier. It used to be thicker. Had a maple taste. Anyway, where were we? Oh, yeah. Gender dysphoria. I didn’t think the science with those treatments was very clear. You know, like effectiveness and long-term side effects.”

Cain nodded. “It’s not. In their 2022 revision, WPATH stated as much (Source). Anyway, that got me to thinking about rights in general, and Robert Nozick’s Theory of Rights.”

Abel asked, “Refresh my memory. Nozick, the libertarian guy?”

Cain replied, “Yeah. In 1974, his book Anarchy, State and Utopia was published. It basically set out the principles of the libertarian movement. His theory of rights was that people should be permitted to do anything that does not violate the rights of others.”

Abel argued, “Yeah, but who decides the bounds of those rights? I mean, women had a right to have an abortion, then the Supreme Court decided they didn’t. Gays did not have a right to marry until the Supreme Court decided they did. We recognize a right to self-defense, ok? But not if you’re resisting arrest. But maybe you do if the officer is using excessive or unlawful force (Source).

Cain smirked. “What’s excessive or unlawful? Like there’s a referee every time someone encounters a police officer.”

Abel nodded. “Right. That’s why bystanders take videos of an arrest with their cell phones. Some kind of public witness.”

Cain continued, “So Nozick argued that a state’s proper role was to enforce the sanctity of individual rights. The courts, a police force, that kind of thing. A federal government should provide for the common defense against foreign powers. You pointed out a big flaw in Nozick’s argument. What are those rights?”

Abel replied, “Yeah, the right to free speech, for instance. Countries set different boundaries on that right. In Britain, the burden of proof is on the defendant, the person accused of committing the libel. In the U.S., it’s the plaintiff, the accuser who has the burden of proof (Source). Two entirely different approaches to defining the limits of a right.”

Cain frowned. “That brings up the subject of what’s called ‘positive’ rights. You know, like FDR’s Four Freedoms. The first two were already in the Constitution. Freedom of speech and worship. But the other two were freedom from want and freedom from fear. So, is it the federal government’s responsibility to ensure those last two freedoms?”

Abel replied, “That is at the heart of the debate for the past eighty years. Is there an obligation to help the poor? If so, whose responsibility is that? In 17th century England, the local parishes administered relief for the poor (Source).”

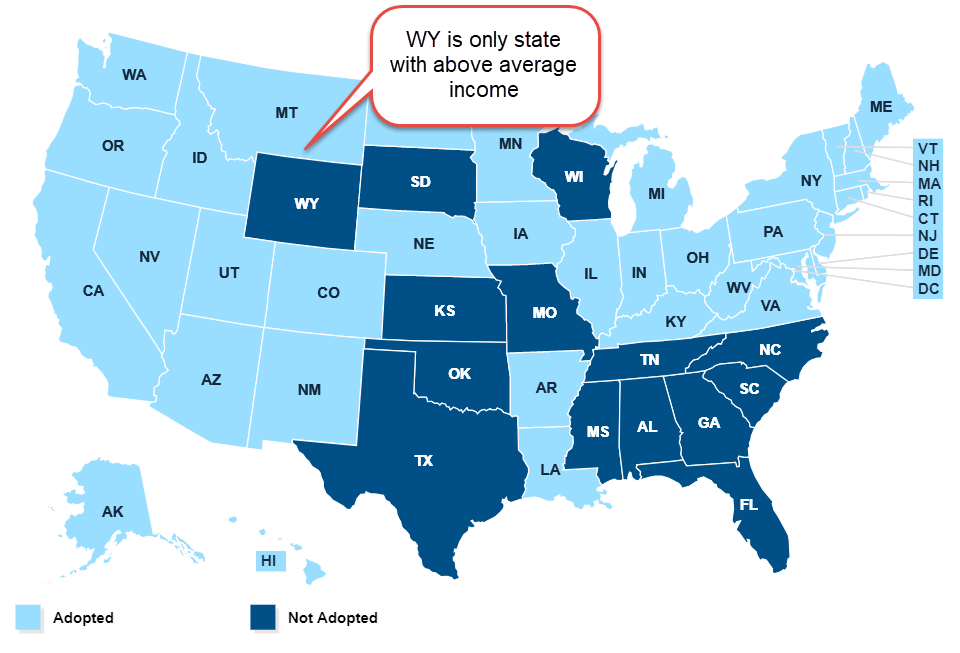

Cain nodded. “That’s the way it should be in this country. Means tested programs like food stamps, Medicaid, and welfare should be handled by the states or local governments.”

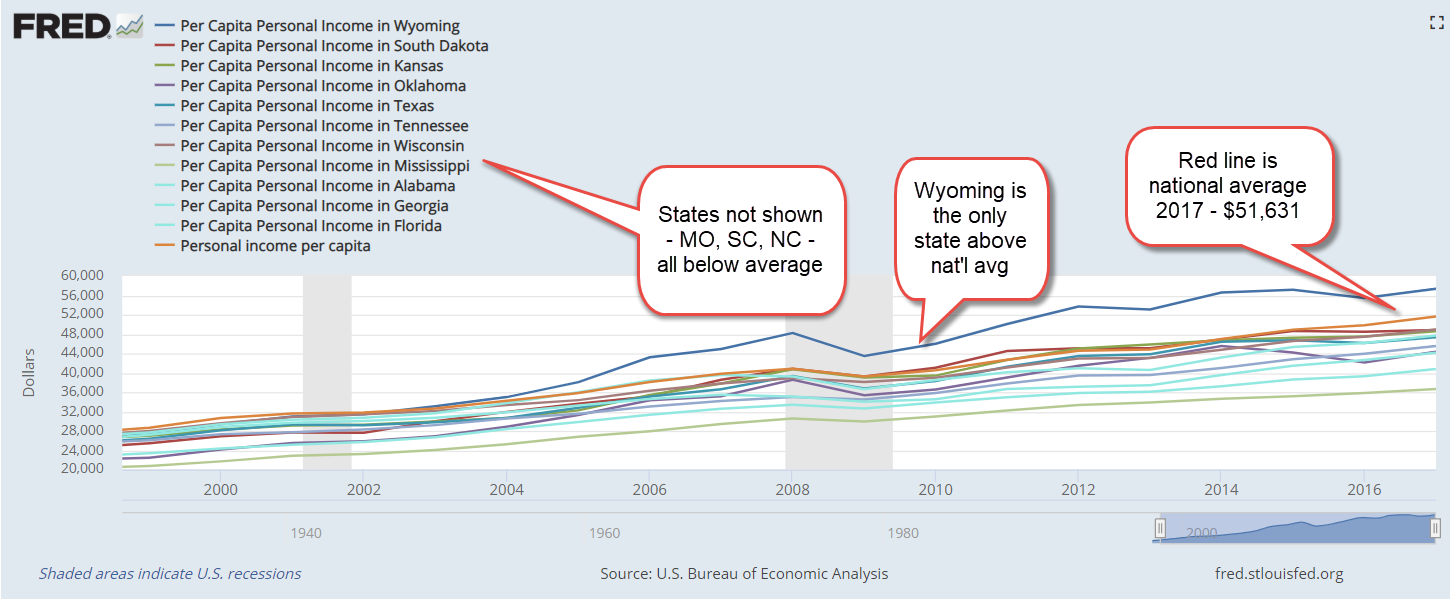

Abel asked, “And pay for it how? In England, they charged an extra poor rate on property owners. So let’s say, a city has an above average rate of poor people and low property values. How is the city going to handle that? What about poor states in the deep south? They rely on federal funding. Mississippi gets like an additional $30 billion a year in federal funds (Source). Without those funds, people would start to migrate to states with more resources. That was a big problem in England.”

Cain argued, “I don’t think there would be a lot of migration. A richer state would be more expensive to live. It’s probably a more competitive job market. Besides, it takes resources to move. Something that a lot of poor people don’t have.”

Abel said, “I just think that policies founded on libertarian principles will have some bad consequences. The bad would overwhelm any good.”

Cain paused as he looked over his coffee cup at Abel. “All these federal programs create a sense of entitlement and dependency. People start making up rights to this, rights to that. Sometimes less is better.”

Abel sighed. “Yeah, kids can do with fewer dolls. That’s what Trump said. Not very charitable.”

Cain stared at his plate, deep in thought. “Taxes were high in the 1980s. I only took home 75% of my pay because of various taxes. I was young and I wasn’t making much. They kept raising the Social Security tax rate because the system was going bust then.”

Abel interrupted, “I agree. It sucked. High inflation, tough to pay bills as it was. Then all these small increases in taxes. It adds up.”

Cain continued, “So, older people were collecting far more than they had paid into the system during the first decades of the program. If they had paid anything, they felt entitled to collect. Social Security had become a big charity program, a transfer of money from the young to the old. That taught me a thing about rights. They had rights. I had none. That’s what it felt like.”

Abel argued, “I was young. I didn’t appreciate that Social Security is essentially an insurance program, an old age insurance program. I mean, old age was an eternity away. Hard to imagine getting wrinkles and ‘turkey neck,’ we called it. I thought old people looked that way because they didn’t get enough vitamins back in the old days.”

Cain laughed. “Ok, good point. We get older. We get a longer term perspective. Can the insurance company, the government, make good on its promises? Did it collect enough in premiums to pay out those promised benefits? No. It’s a badly managed insurance program. Why? Because the premium rates are set by politicians who don’t have the guts to charge an appropriate rate, a tax that is proportionate to the promised benefits. What’s the term? Actuarily sound. That’s why the program is going to run out of money in eight years, and the program will pay out reduced benefits (Source).”

Abel argued, “You call the politicians gutless. Because they are gutless, they will use general funds to make up the difference. They will be forced to, or the voters will throw them out of office.”

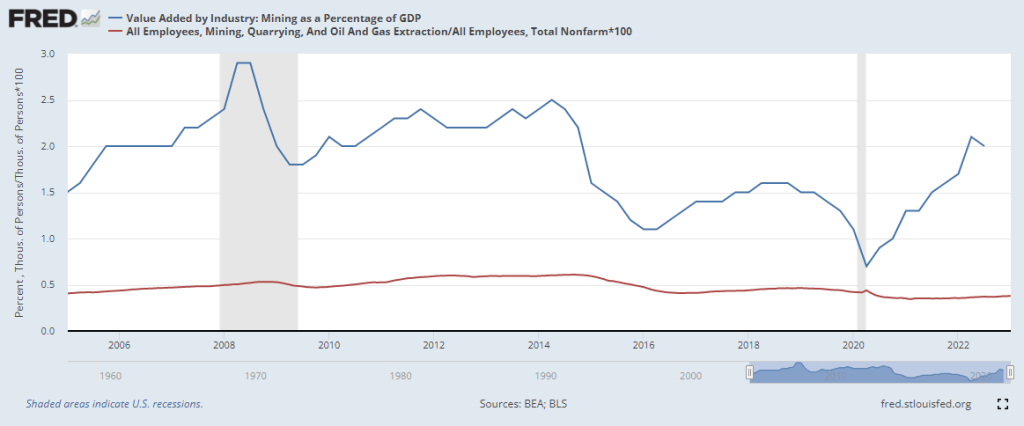

Cain asked, “How are they going to do that? This new spending bill reduces taxes even further and increases the deficit each year (Source). No, each side is going to use this issue as a weapon against the other side. Look, Social Security has not been very effective at reducing poverty among seniors. Google dug up an old Census Bureau report from 1966 that shows a poverty level of about 18% among seniors. This was before taking into account Social Security and Medicare and any other programs (Source). Today, after including the income from all those programs, it’s about 15% (Source).”

Abel argued, “Well, a 3% reduction is a lot, I think. Hey, here’s food. Thank you.”

Cain shook some pepper on his eggs. “Hold on. That’s not all. That old report estimated that about 12% of kids under 18 were poor (Source). What is it today? After all the programs, it’s gone up, not down. It’s almost 14% (Source). So, the government is essentially taking from families with young kids and giving it to seniors with no kids. Does that seem fair or effective to you?”

Abel frowned. “You know what I don’t like about your thinking? It’s uncharitable. Why don’t we have more of a sense of community? There were childless couples who had to pay property taxes to fund public schools. We benefited from that but never gave it a thought. Think of it as a game of poker. We throw money into the pot and sometimes we get back more than we put in. The winner of a hand is richer. The other players are poorer.”

Cain swallowed, then replied, “No, I think it’s your attitude that is uncharitable. “There’s all these kids whose outlook and personalities are going to be affected by that poverty for the rest of their lives. Some learn to be passive and helpless. Some rebel and turn to drugs and crime as a way to empower themselves.”

Abel interrupted, “Until they go to jail or get shot by another gang.”

Cain nodded. “Right. This is not a prudent long term strategy, let’s say. In prison, they sit around in a cage. Can’t get more helpless than that. I just think that all these big federal programs have ruined the character of this country. What happened to self-reliance? The states have become little more than departments in a big company taking orders from the bosses in Washington. They send a lot of tax money to Washington, then go crawling to Washington when they need something.”

Abel said, “We were talking about rights before, the so-called positive rights. Freedom from want. Freedom from fear. After eighty years, you are saying that ‘big daddy’ government is a failure?”

Cain nodded. “Exactly. This country doesn’t have a great record on rights. The Declaration cites all these universal rights, but those rights were not universal. Women were excluded. Blacks, American Indians, later the Chinese. Businesses could form trade associations, but labor unions could not go on strike. It wasn’t until the 1937 NLRB decision that the court recognized workers’ right to organize (Source). Women didn’t have the right to vote until 1920.”

Abel argued, “I thought you weren’t a big fan of unions.”

Cain replied, “I might not like the strategies that unions use, but I’m a big fan of consistency. If businesses can engage in quasi-collusion through trade associations, then workers should be able to do the same. I do like right-to-work laws. I don’t think employees should be forced to join a union to be employed at a company.”

Abel asked, “That’s why you don’t like Social Security? In a sense, you’re forced to join, to buy into the insurance program? I mean, that’s part of living in society. We trade some freedom for security. To me, your ideology seems too rigid.”

Cain laughed. “They’re called principles. Your approach seems too arbitrary. Where you conform to the circumstances of the moment.”

Abel smiled. “Marginal thinking. I’m practical. A few weeks ago, we talked about Stephen Breyer’s book on taking a pragmatic approach when evaluating court cases. That’s me. Mr. Practical. So you mentioned the spending bill that’s working its way through Congress.”

Cain smirked. “ The One Big Beautiful Bill Act, as it is now known. They should call it the One Big Bloated Bill.”

Abel interrupted, “They are going to cut back on Medicaid, which is going to hurt a lot of poor people, both kids and seniors. You talked about how much states are spending on Medicaid. A lot of that is on seniors. In California, seniors cost almost twice the state’s average on their Medicaid program (Source). California spends about $90,000 per year for a senior in a nursing home. What’s your plan? Put them out on the street?”

Cain asked, “Do you think that California could handle that load with its own resources?”

Abel nodded. “Sure. The problem is that California kicks in a lot of tax money to the federal government and gets far less back from them. That amounts to $90 billion in a year, a huge hole that California has to fill (Source). New York and Texas have similar holes. The feds take that tax money and give it to rural states that are usually poorer.”

Cain raised his eyebrows. “Is providing health care a state and local thing, or a national thing that the federal government should do?

Abel argued, “Well, health care insurance is a deductible expense for businesses, so that makes it a national issue. Businesses spend money on health insurance for their employees, but people don’t have to declare it as income. It’s the largest subsidy by the federal government to working people and businesses (Source). Why should some working people get a subsidy and others don’t? Is that a violation of the 14th Amendment?”

Cain shook his head. “That’s the problem. The tax deductibility of health insurance was a World War 2 policy. Because there were wage freezes in place during the war, companies wanted a way to attract employees. Health insurance was one of those. Again, we are saddled with the effects of a policy that ‘big government’ FDR started. As soon as the war was over, that program should have ended. Period.”

Abel shrugged. “Yeah, fat chance. It was tax-free money. No one wants to give that up.”

Cain replied, “Exactly my point. These big federal programs are like fishing boats coming back from a big catch. The gulls stay with the boat, wanting an easy meal.”

Abel argued, “Well, companies do the same at the state level.”

Cain smirked. “States must balance their budgets even if it does take some accounting tricks. So states have some constraint. The federal government has no such discipline other than the probability that generous federal transfers will cause inflation.”

Abel shook his head. “There’s like seven rural hospitals that close every year (Source). Remember, that’s with the Medicaid expansions under Obamacare. So, if Medicaid is severely reduced or eliminated, most rural hospitals will fail. I just don’t understand why the representatives of these rural states vote to reduce Medicaid. And for what? To keep giving big tax breaks to billionaires?!”

Cain sighed. “It’s the principle of the thing. Medicaid programs encourage people to drop private insurance in favor of a low cost government program. This ultimately has an effect on the larger market for employer sponsored health plans and drive up private insurance rates. The federal government covers a lot of the cost, but the states still have to cough up like 10% of Medicaid costs and it’s a huge program. Texas spends almost half of its state budget on Medicaid (Source).

Abel whistled softly. “Wow, I didn’t realize it was that much.”

Cain smiled. “You wouldn’t because you mostly consume left wing and mainstream media. Even the blue states struggle to pay their share of Medicaid. New York and California spend almost 40% of their budget on Medicaid. College students complain about the high cost of education but part of the reason for that is the states pick up less of the cost of higher education than they did like forty years ago. Why? Because Medicaid sucks up so much of each state’s budget. So college kids are basically paying for greater access to Medicaid. Is that fair? No, of course not.”

Abel argued, “That’s bogus. State spending on higher education has increased by $2000 per student over the past forty years (Source). That’s after adjusting for inflation. The real problem is that colleges have been raising tuition and housing prices for students at a faster rate than inflation.”

Cain sighed. “Come on. First of all, the schools have had big cost increases because of federal mandates. They have to present the material in a lot of different formats tailored to different learning styles. They have to make allowances for disabilities and special needs. That takes time and resources. The students themselves make it worse. They find a doctor who says they have some learning disability which entitles them to have more time taking tests or completing assignments. Some of those claims are legitimate. Some are simply working the system, trying to gain an advantage. The school has to deal with that.”

Abel argued, “I think a lot of those additional costs are not simply because of federal mandates. Learning has changed. Students spend a lot of time on computers or their phones. The curriculum has to be modified to accommodate that. The cost of housing has increased at a slightly higher rate than overall inflation (Source).”

Cain replied, “Ok, I’ll grant you that. But how much are schools spending on administrative costs? One organization said that those costs had increased by 61% in the twelve years before 2007 (Source). Ok, that’s not inflation adjusted but after accounting for that, administrative costs are going up an additional 2% above inflation. The Department of Education also estimates a growing share for administrative costs, like 16 cents of every dollar in 1980 has now grown to 25 cents of every dollar. These federal programs are not efficient. They rob from Peter to give to Paul. That’s my point. Social Security, Medicaid, and education mandates. Everywhere you look.”

Abel laid his napkin on the table. “I agree with you that a centralized structure has problems. But I think your approach is impractical. We have to live with the decisions that previous generations made. I believe we can patch some of the problems in these programs. Right or wrong, employer-sponsored health care is here to stay. Right or wrong, private insurance companies will not cover the medical risks that come with old age. Right or wrong, people don’t save enough for their retirement. That’s just the way it is.”

Cain settled back in his seat. “I still think that these problems would be better handled at the state or local level. My point is that they are not effective at the federal level.”

Abel stood up. “Half of the states have limited resources. We saw that during the pandemic. Rural hospitals in one state sent their patients to hospitals in other states. Idaho sent patients to Washington (Source). Wyoming sent patients to Colorado. Solutions to any problem have to deal with those hard realities. Does that involve a compromise with principles? Maybe.”

Cain looked up. “You’re ready to go. Maybe we can continue this next week. See you then.”

Abel replied, “It’s a huge problem, isn’t it? See you next week. Where’s the check?”

Cain said, “I think it’s my turn. I can’t remember. You go ahead and I’ll pick it up.”

/////////////////////

Image by ChatGPT in response to a prompt

Note: The standard poverty measure does not include any government transfers like Social Security. The Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) includes those transfers. The 1966 study used the conventional poverty measure. The recent poverty measure was the supplemental variety. Cain contrasted the two to show the relatively small reduction in poverty that the sum of government transfers has had over the decades. The 1966 study showed that a significant reduction in poverty before Johnson’s Great Society programs had taken effect. The strong economy of the early 1960s played a significant part (Source).