June 29, 2025

By Stephen Stofka

Sunday morning and another breakfast with the boys as they discuss world events and persistent problems. The conversations are voiced by Abel, a Wilsonian with a faith that government can ameliorate social and economic injustices to improve society’s welfare, and Cain, who believes that individual autonomy, the free market and the price system promote the greatest good.

Cain smiled as he asked Abel, “You used to live in New York. So, are they getting ready to elect their first socialist mayor?”

Abel chuckled as he spread the linen napkin across his lap. “Mamdani is the Trump of the left. Knows how to work social media and promises he’ll make food and housing affordable again. Just like Trump. Neither one of them has a workable plan. Maybe that’s the age we live in. The age of blowhards on social media. Anyway, I wanted to ask you what you thought about the court’s decision this week. Can lower level courts issue nationwide injunctions? What’s the verdict, Mr. Court Watcher?”

Cain stared into his coffee cup then looked at Abel. “Well, I liked that part. Last year, Reuters did a study (Source). There have been almost 130 injunctions issued in the past sixty years. So, during the 1960s and 1970s, there were two injunctions. Two! Then it got political. Sixty injunctions during Trump’s first term. California judges were a go-to for Democrats. Maybe twenty injunctions during Biden’s term. Republicans running to Texas judges. Now the Democrats have started again in Trump’s second term. It’s abusive tit-for-tat.”

Abel asked, “So you like the decision? How did it stand up to the famous Cain consequentialist rule?”

Cain held up his right hand, thumb down. “Failed. It confuses more issues than it clarifies. The court stayed Trump’s executive order for thirty days. Not a whole lot of time to get a class certification and a whole bunch of procedures (Source). A district judge can issue an injunction on the likelihood of class certification, but it only applies to the parties named in the suit (Source). Meanwhile there will be confusion everywhere. Confusion equals bad court decision in my book.”

Abel lifted his eyebrows. “A ‘Keep It Simple, Stupid’ approach. But this decision permits the White House to keep drafting unconstitutional orders then enforce them wherever there is no applicable injunction. I mean, this is a case where you can’t separate legal rules and procedures from the merits of the case, the Constitutional right to citizenship at birth.”

Cain frowned, then settled back as their food arrived. “Justice Sotomayor basically made that point in her dissent. The consequence of the court’s ruling is that the burden of protecting our constitutional rights falls on ‘we, the people.’”

Abel pursed his lips. “That’s expensive.”

Cain sighed. “It’s also depressing. Anyway, change of subject. We were talking last week about the One Big Beautiful Bill, the cuts to Medicaid.”

Able interrupted, “Oh yeah, why people vote against their best interests. What was that book? What’s the Matter With Kansas? Thomas Frank.”

Cain nodded. “So you said you didn’t understand how Republican representatives could propose cuts to Medicaid that would hurt their constituents. I said that it was the principle of the thing and the huge costs to the states even after the cost-sharing with the federal government.. So, I was reading this week that some of the Republican members are concerned about the blowback from voters in the midterms (Source). “

Abel glanced at his phone. “Boy, I love this thing. My personal librarian. Last week, you made me aware of how much the states were spending on Medicaid. I did some digging this past week and I was surprised at how dependent we all are on Medicaid. It’s red states, blue states. Did you know that Medicaid finances 42% of all births (Source)?”

Cain shook his head. “Wow, I didn’t know it was that much. Now I’m remembering Romney’s remark about the 47% dependent on federal programs. He might have lost the 2012 election over that but maybe that’s what he was talking about.”

Abel frowned. “You know, when I think of poor rural states, Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama come to mind. They have high percentages of children who are covered by Medicaid. Like more than 60% in some cases. North Dakota is up there at 63%. Kansas and Iowa are above 50%. But there’s also blue states in that category. In Minnesota, it’s more than 60% and in Colorado it’s more than 50% (Source).”

Cain asked, “Colorado is a blue state? I thought it was purple.”

Abel shook his head. “Nah, they have a trifecta now. Governor, state House and Senate. All Democrat. In fact, most of the states have trifectas now, like almost 40 states (Source). Shows how polarized we are in this country. Forget about what happened to Kansas. What happened to divided government?”

Cain smiled. “For many years, that’s how I voted. I was against the Democrat, Republican duopoly. If Republicans held a lot of seats, I voted Democrat just to keep a balance of power. Groups get crazy when they have all the power. What did you call it? The monster in us. We start to uncage the monster. We want to enact revenge. We want what we want just to enjoy the power of getting what we want.”

Abel raised his eyebrows. “Wow, talk about dark. Well, you weren’t alone. I was reading that, in the 1970s, voters split their ticket like 30% of the time. That started to decline in the 1980s. Now, it’s less than 5% (Source).

Cain nodded. “Like I said last week, we’re in our silos. We got our political clubhouses with big signs that say, ‘Keep Out!’ That’s why I believe in the price system, supply and demand. Keeps people from getting their own way.”

Abel frowned. “You’ve talked about that before. I mean, how does a price system work in a democracy?”

Cain smiled. “I’ll talk about it another time. It’s simple. Most of us have social security numbers. Everybody living in a state votes, whether they cast a vote or not.”

Abel looked puzzled. “How would that work?”

Cain gave a Cheshire grin. “Not this week. Anyhow, back to Medicaid. So, I said last week that a lot of Republicans don’t respect dependency. It’s a bad word. That’s why they are against these big federal programs.”

Abel interrupted, “That’s you.”

Cain nodded. “Yeah, but I’m not against dependency as such. We’re all dependent on each other in a lot of ways that we take for granted. That was Adam Smith’s point. My eggs here. Someone had to grow them, spread feed, and muck out the chicken coops. I appreciate that when I eat eggs. I’m connected to those farmers.”

Abel interrupted, “An illegal immigrant probably mucked out those chicken coops.”

Cain nodded. “Yeah, or the farmer’s kids before they went to school that morning. People who work hard. Eggs are under $3 a dozen now after the industry has recovered from the mass killing of chickens to stop the virus (Source). So, it’s like 25 cents an egg. That’s less than a minute of someone’s hourly wage, let’s say. So the farmer, the kids, or the illegal immigrant, as you point out, work their butts off and I get to buy an egg for less than a minute of work. A great deal.”

Abel set his water glass down on the table. “You put it like that, and I can understand the two different worlds perspective.”

Cain mopped up some egg yoke with his toast. “What were the two groups in the Time Machine story? The Eloi and I forget the name of the other group. In Wells’ book, they represented the working class of England (Source).”

Abel smiled. “The Morlocks. So, you’re saying that the Eloi are urban dwellers and rural people are Morlocks? That’s kind of stretching an analogy.”

Cain laughed. “No, not exactly. The Eloi are the ‘haves’ and the Morlocks are the ‘have-nots.’ That’s what I’m thinking. In any society, there are those two groups. That was Machiavelli’s point in the Republic. He thought the haves were the more dangerous group because they fought harder to keep what they had.”

Abel whistled softly. “Whoa. From Medicaid to political philosophy. Let me buckle my seat belt. Although, now that I think about it, that was a big cause of the Civil War. The plantation owners in the South wanted to keep on expanding. I was reading Alan Taylor’s book American Civil Wars and I was shocked to learn that Lincoln agreed to let the southern states keep slavery legal. This was even before the war started. His red line was no more expansion into federal territories or any new states. If the slave owners had agreed to that, would we have avoided a civil war? Anyway, the slave owners needed to expand to keep up the value of their slaves. New markets, new demand.”

Cain smirked. “A rich man’s war, for sure. Can you imagine paying a substitute to fight instead of your own son? (Source)”

Abel shrugged. “Reading that book, I could understand why we don’t learn a lot of that stuff in grade school. Too dark for grade school kids.”

Cain interrupted, “It’s the monster inside. So, you think the Republicans who vote for Trump’s big, beautiful bill are heartless?”

Abel replied, “No, I think that Trump is gambling that he won’t lose that much support from blue-collar workers even if those voters lose some or all of their Medicaid. These rural states showed strong support for Trump in the 2024 election (Source). They elect far more Republicans than Democrats to Congress (Source). It’s a political gamble. He’ll blame Democrats if he’s wrong.”

Cain frowned. “Yeah, but if that gives Democrats enough support to flip the House, they will try and block his agenda in the last two years.”

Abel shook his head. “He’s a gambler. He ran for President in 2016 to boost his brand. His businesses were failing, and he had trouble getting financing (Source). He didn’t think he had a chance to win the Presidency (Source). He admitted he didn’t know what he was doing his first term in office. He’s rolling the dice this term.”

Cain sighed. “Talk about the Time Machine. I wish I could get in a time machine and go to four years from now. Trump, Trump, Trump all the time. I kind of miss the days when we talked about who shot J.R. on the TV show Dallas, or something like that.”

Abel laughed. “I think there will be someone like Trump after Trump. Someone who knows how to maximize social media. Kyla Scanlon on Substack used the word ‘virality’ (Source). Someone who knows how to go viral. We talked about Mamdani earlier. He’s the same. Maybe that’s the new vanguard in the political arena. We will only elect people who get and keep our attention.”

Cain shook his head. “God, I hope not. So, we were talking about two groups, the haves and have-nots. I accept the fact that there will always be inequality in society. Life is multi-dimensional so it’s impossible to have equality. Each of us is like a soap bubble on an ocean wave. We’re all at different locations and elevations, different times in our lives.”

Abel raised his eyebrows. “That’s a good point, but I think a lot of us would like to reduce the growing economic inequality in this country. You think that these big government programs just aren’t very effective. That’s what you said last week.”

Cain nodded. “I think the data backs me up. The best way to reduce inequality is more economic growth. More jobs, more opportunities, more income. Democrats just focus on redistributing the profits. It’s like someone who spends all their time adjusting the heat vents in a home so that everyone feels comfortable. The problem is that Democrats don’t do maintenance on the furnace itself. Then the furnace breaks and no one has any heat.”

Abel chuckled. “Yet, economic growth is stronger under Democratic administrations. More job growth, lower unemployment, higher GDP growth (Source). Using your analogy, it’s the Republicans who don’t maintain the furnace. They make sure the gas valve is wide open. Low taxes, big investment. Republicans expect that the furnace will just keep running. Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand. The will of God, or something.”

Cain laughed. “Ok, you ran away with my analogy. You are watching too much Democratic propaganda. Under eight years of Obama, real per capita economic growth increased 11%. In Trump’s four years, it increased almost 7%. On an annualized basis, that’s better than Obama. Under Biden’s four years, it increased 8%. The big winners were Reagan and Clinton with 20% growth during their two terms (Source).”

Abel tapped notes in his phone. “You’re using per capita growth?”

Cain nodded. “Sure, that’s what people care about. If there is a bigger population, there will be higher overall growth. You have to divide by the population to get a sense of what people are experiencing in their daily lives.”

Abel nodded. “Ok, makes sense. The thing is, there was a lot illegal immigration during the Reagan administration. That’s why he agreed to grant amnesty in 1986 (Source). There was still high growth.”

Cain smirked. “And high deficits, don’t forget. Reagan had to work with a big spending Democratic Congress. And he needed to rebuild the military after the Carter administration.”

Abel laughed. “Sure, it was all the Democrats fault. For the first six years Reagan had a Republican Senate, don’t forget. Clinton raised taxes and there were actual budget surpluses and big growth. So Republicans are against illegal immigration and taxes but neither of those interfered with economic growth during the Reagan and Clinton administrations. So, what’s the secret sauce, professor?”

Cain grunted. “I’m just saying that Democrats need to focus on economic growth more than income inequality.”

Abel sighed. “You’re using per capita economic growth but that doesn’t capture the real effect of inequality on households since the start of Reagan’s first term.”

Cain shook his head. “No, remember we talked a little bit about this. The official measure of inequality doesn’t capture a lot of the income and benefits that lower households receive. In 2016, a Congressional Budget Office found a much lower GINI coefficient than the Census Bureau reported (Source). That lower figure was after taxes and government transfers were accounted for. The World Bank also computes a GINI coefficient that is closer to the CBO estimate (Source).”

Abel asked, “Does that include Medicaid or food stamps?”

Cain shook his head. “No. There is a lot of what’s called ‘in-kind’ support for lower income households that is not included in these inequality measures. Section 8 housing vouchers. The Census Bureau lists all the different types of income streams and which are counted (Source). Yet Democrats just throw these inequality figures around without acknowledging the subtleties.”

Abel interrupted, “Ok, I’ll admit that housing support can be sizeable. I had customers who paid maybe $300 for an apartment that normally rented for like $1500. Ok, go on.”

Glancing at this phone, Cain continued, “Yeah, so that’s like almost $15,000 in after-tax income and it’s not counted. Food stamps or SNAP, they call it now, are not included and neither are school lunches. Medicaid, Medicare and employer health insurance are not counted (Source).”

Abel said, “So, I’ve been reading about all the horrible things Americans did to each other during the Civil War, and you’ve been digging up data. Ok, so how much was it before and after all these in-kind transfers?”

Cain replied, “Well, the GINI coefficient before those was .42. Lower numbers mean more equality of incomes.”

Abel interrupted, “What’s Mexico and Canada?”

Cain looked up at the ceiling, searching his memory. “Mexico is about the same as the U.S. Canada is low. Like 30 or so.”

Abel nodded. “Ok, so what was the GINI coefficient after including in-kind transfers?”

Cain shook his head. “I couldn’t find a GINI number for that. I mean, there are so many income measures. Before tax, after tax, with transfers, without, with capital gains and without. Survey data like the Census Bureau or figures from IRS tax records.”

Abel smiled. “Like you said, it’s complicated.”

Cain sighed. “Yeah. Some researchers have developed an ‘augmented’ income measure that adjusts a conventional measure called the ’90/10 ratio.’ You know, they compare the top 10% to the bottom 10%. One paper estimated a 30% reduction in that ratio in 2012 (Source).”

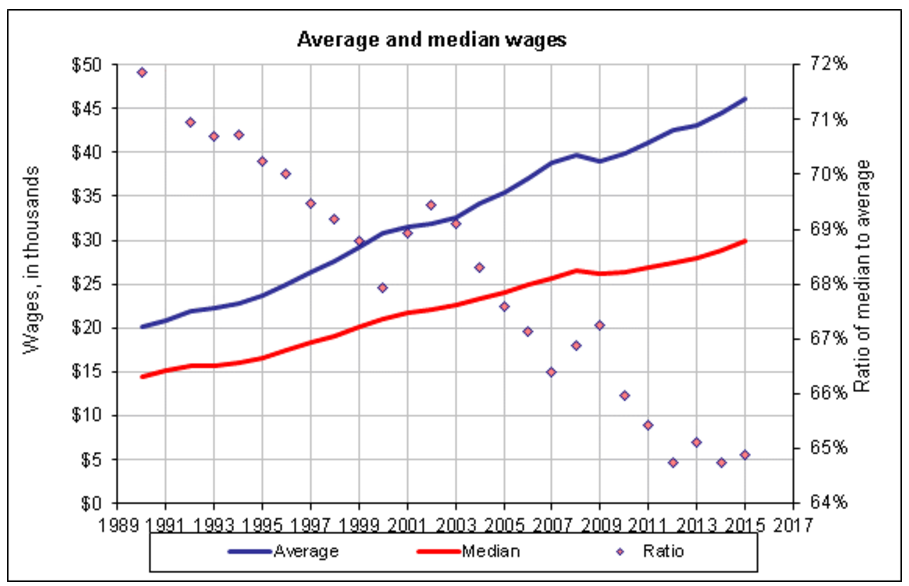

Abel smiled. “That sounds like a Bernie Sanders measure, comparing the very top and very bottom. What was the top compared to the middle? I’ve read that top incomes have been growing a lot faster than median household incomes.”

Cain squinted at his phone. “Geez, I need new glasses, I think. Hold on. Ok, that 90/10 ratio grew by a third between 1980 and 2018 (Source).”

Abel interrupted, “No taxes figured in?”

Cain shook his head. “No, just cash income. They do subtract capital gains. You know, they are trying to measure current year income (Source).”

Abel asked, “Ok, so do they compare the top and the middle?”

Cain expanded his screen with a flick of two fingers. “Yeah, it’s called a 90/50 ratio. So the top 10% has grown a lot. From 1979 to 2012, their incomes grew like 30%. The middle only grew by 7% (Source).

Abel nodded. “So that shows what I was talking about. The top has grown four times as fast as the middle in the past few decades. They are doing way better than the middle and yet the Republicans want to keep cutting taxes on the top. You’re saying that these inequality measures don’t include food stamps and housing vouchers and stuff like that. Well, the middle is mostly not getting those, so there’s no confusion. I mean, you can see the inequality in the data.”

Cain argued, “It’s a lot more complicated than that because the top 1% skew the comparison so much. If you dig into the income data for 2012, you find that the top 1% had 40% of the income in the top 10%. An income measure used by the Congressional Budget Office shows that the top 1% now have almost 14% of total income. That’s almost tripled (Note).”

Abel argued, “Ok, so what’s the 99/50 ratio, I guess it would be called. What’s that?”

Cain sighed. “The BEA didn’t have that.”

Abel sighed. “You seem skeptical about the accuracy of the measures themselves.”

Cain replied, “I am. The GINI coefficient jumped up like 6% in two years during a slight recession in 1990 and 1991. That tells me there was some change in the categorization of incomes, some anomaly in those years. During the Great Recession, that coefficient only dropped 2%. Like I said, there’s something doesn’t make sense about that jump in 1990.”

Abel said, “I want to do some research on poverty, but I suspect I’m going to run into the same problem. A lot of different income streams and measures of poverty?”

Cain nodded. “Exactly. The Census Bureau uses self-reported income, and several studies have found that lower income households underreport their income. One study compared self-reported income to actual Social Security checks sent to the people in the study and found that their reported income was lower than what they actually received (Source).”

Abel asked, “How much lower?”

Cain shrugged. “Well, it wasn’t a lot, like 7-8%.”

Abel replied, “So, slight underreporting of lower incomes. That’s not going to change the picture all that much. Income inequality is still a problem. Maybe a little bit less, but not a whole lot.”

Cain smiled. “I can see that I haven’t convinced you to focus on economic growth.”

Abel argued, “I think you are taking some slight imperfections in measurement and using that to cast doubt on the whole idea that inequality is a big problem in this country. During the Clinton years, taxes were raised on higher income families and that basically stopped the growth of inequality under Reagan and H.W. Bush (Source). Republicans just keep fighting any Democratic effort to reduce inequality through higher taxation.”

Cain shook his head. “Clinton was an anomaly. A lot of investment poured into the tech sector and stock prices tripled during Clinton’s eight years (Source). The result of that was a lot of capital gains taxes. It was an anomaly. Normally, higher taxes hurt economic growth. End of story.”

Abel let his head fall. “If we can’t resolve the disagreements in this country with the available data, what hope is there? I think of the story of the blind men touching different parts of an elephant and trying to identify it. If one person is convinced it’s a snake they will just keep searching the animal for a trunk then reason that the snake ate a big meal and is lying on a table with four stout legs.”

Cain laughed. “It’s like our brains are tuned to specific types of information. You know, the way our eyes see the world differently than birds or dogs.”

Abel said, “Well, nice data hunt this week. I just wish you would look at things the correct way. You bought last week. I’ll pick it up this week.”

Cain smiled. “Well, if you are buying, then I totally agree with you. See you next week.”

///////////////

Image by ChatGPT

Note: Clarke, C., & Kopczuk, W. (2025). Measuring Income and Income Inequality. https://doi.org/10.3386/w33678