November 10, 2024

By Stephen Stofka

The country has elected a fortunate son for the second time. Throughout his life, Donald has enjoyed the protection of a phalanx of lawyers who have kept him out of jail. A recent decision by the country’s highest court will give him immunity for another four years. His physical condition and cognitive health are declining so rapidly that he likely will not serve out his full term. His much younger Vice-President J.D. Vance will become President and possibly the leader of the MAGA movement for another eight years.

Another take. Former President Donald J. Trump has made the greatest political comeback in the history of this country. Millions of supporters donated money to his legal efforts to defend the integrity of the vote and challenge voter fraud by the Democratic Party. Despite persistent persecution by Democratic prosecutors, Mr. Trump has emerged victorious. In the days leading up to the election, the former President held many rallies, demonstrating the vitality of a candidate twenty years younger.

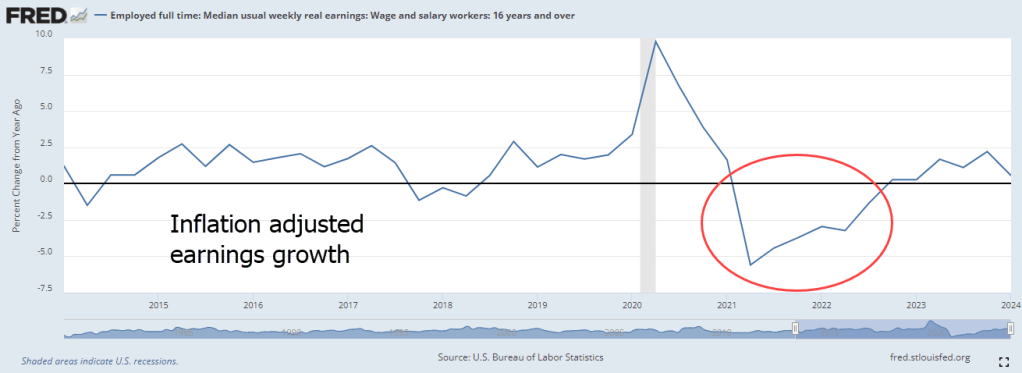

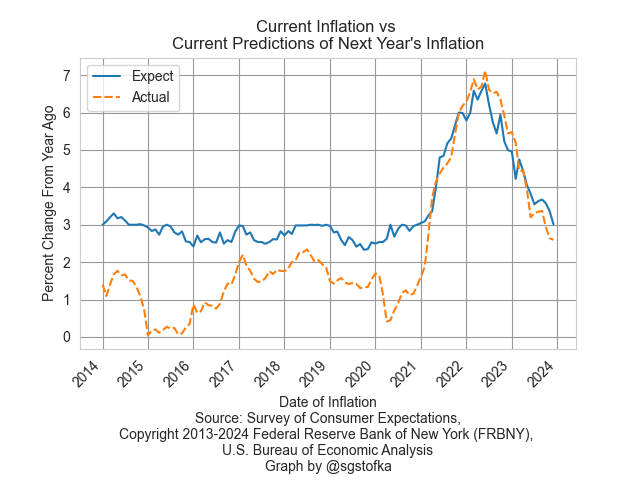

Yet another take – a just the facts, ma’am perspective. Presidents with low approval ratings, including Trump in 2020, do not win reelection. This election’s results repeated that trend. James Carville, Clinton’s campaign manager in the 1992 race, coined the famous phrase “It’s the economy, stupid.” Voters showed more concern about inflation and immigration than Trump’s character and demeanor. Voters are especially sensitive to inflation because they feel helpless, and people do not like feeling helpless.

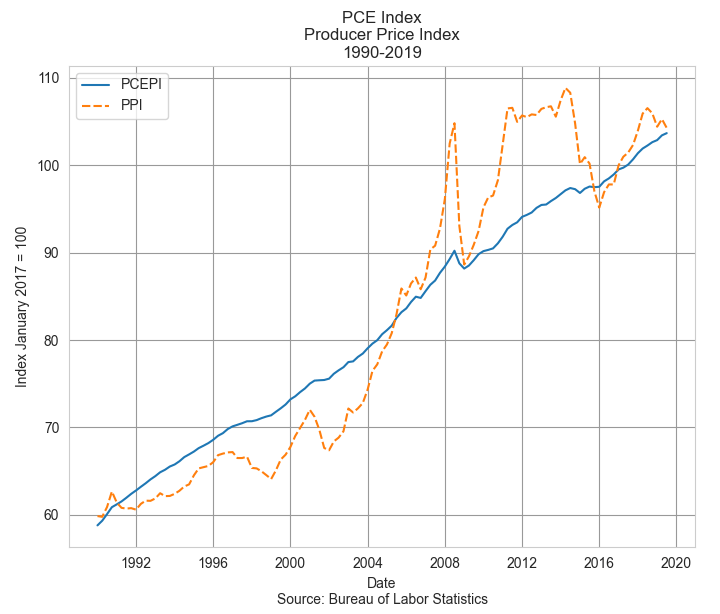

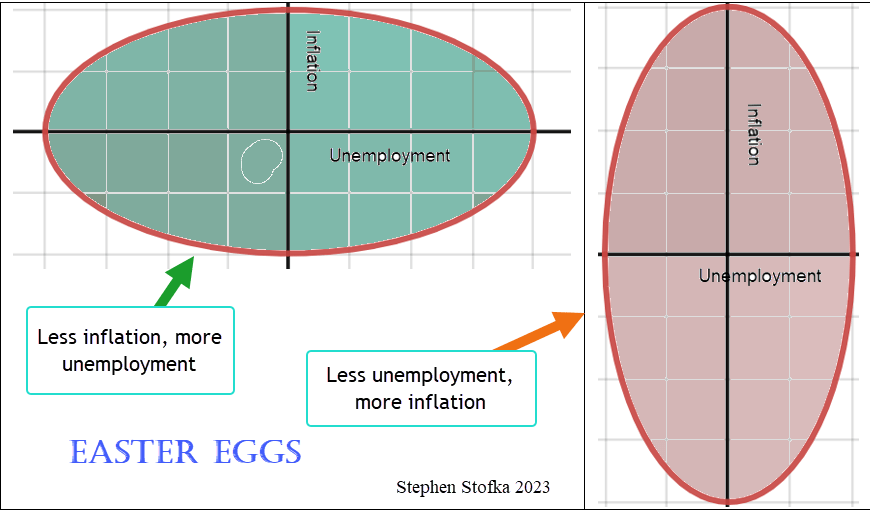

The misery index is the sum of the unemployment rate and the inflation rate. A comfortable reading is about 7%. In 1980, the index was 20% and Jimmy Carter lost his bid for re-election. Bill Clinton and George W. Bush won re-election with misery readings of 8%, and Obama won the 2012 election when the misery index was near 10%. In the fall of this year, the index was below 7%. Perhaps the misery index is not a consistent predictor.

Which is your take on the election results? Each second of our day we download terabytes of information into our brains. We filter out much of that data, then arrange what remains into a version of the world that is uniquely ours. Then we interpret that stimuli, integrating it into our memories along well-worn neural pathways. In that integration process, we reconstruct the world again, discarding the information that conflicts with our previous experience, beliefs and values. We shape what we experience, and our experience shapes us. We may be traveling with others on a train through time, but we have a unique vantage point as we look out the window.

In her book Lost in Math, physicist Sabine Hossenfelder writes, “If a thousand people read a book, they read a thousand different books.” Each voter creates a unique election story. Media analysts focus on different elements of an election, creating their own version of the contest, weaving a narrative of cause and effect. In the telling of the election, we should remember Nassim Taleb’s caution, in Fooled by Randomness, that “past events will always look less random than they were.” Since we are rational creatures, we are both frightened and fooled by randomness. In an evenly divided electorate where a few thousand votes in several key counties can make a difference, random events can decide the outcome. A snowstorm in a key state in the days before an election, the path of a bullet at an election rally, a decision by a federal judge.

The percentages of the Presidential election votes were no different than 140 million voters flipping a fair coin.. Heads equals a vote from Trump. Tails was a vote for Harris. Did any individual voter flip a coin? Possibly, but unlikely. As a collective, our individual actions can simulate random behavior. Randomness can make us feel helpless, so we act as though our actions have purpose. We act aggressively or assume a false bravado in the face of random mortal danger. Watch the clip from the Deer Hunter where the prisoners are made to play Russian Roulette.

Those who struggle through life may vote for the calm bravado of someone privileged. Ronald Reagan was known as the Teflon President. The public did not hold him responsible for several controversies and scandals that occurred during his eight years in the White House. In 1981 to 1982, the country suffered the worst recession since the Great Depression fifty years earlier. During the 1983 Lebanese civil war, Reagan ignored warnings that the U.S. Marines barrack in Beirut would be vulnerable to attack. The October 23rd bombing resulted in the loss of 241 lives, most of them Marines. . In his 1984 bid for re-election, Reagan won all but one state, a resounding vote of public approval. In 1986, the Iran-Contra scandal, a secretive trade of arms for hostages with Iran, occupied public attention but Reagan escaped any responsibility or public indignation.

Forty years later Donald Trump can wear that moniker, the Teflon President. A slim majority of voters overlooked his many scandals, his felony conviction, and his chaotic management style during the pandemic and most of his first term. Although the Republican Party’s name remains the same, Trump and his followers have erased the legacy of Reagan. The party’s former symbol, an elephant, has been replaced by a red MAGA hat. It has become a party dedicated not to any consistent set of principles but to one person, a fortunate son.

//////////////////

Photo by Danilo Batista on Unsplash

Keywords: misery index, election, recession, inflation