March 24, 2024

by Stephen Stofka

This week’s letter continues a look at taxes. This week the House passed a series of six spending bills that will avert a partial government shutdown. A majority of Republicans voted against the measure and Marjorie Taylor Greene, the bombastic representative from Georgia, filed a motion to remove Mike Johnson, the current House Speaker. It is unlikely to come to a vote because Republicans have only a one-member majority in the house after Mike Gallagher (R-WI) announced his early departure from Congress. A vote for a new speaker risks the chance that Democrat Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY), the current Minority Leader, might win the vote and become Speaker.

Most Republicans in the House and Senate have taken a “no-new-taxes” pledge called the Taxpayer Protection Pledge. The Americans for Tax Reform (ATR) database lists 191 members of the House and 42 members of the Senate who have taken the pledge. They have committed to not raising income tax rates. Additional tax revenues that arise from eliminating a tax deduction or loophole must be dedicated to lower taxes, according to the ATR’s FAQ page. Republican representatives implicitly committed themselves to increasing deficits but that is an unpopular political stance. They pledged to reduce spending but not military spending, the largest discretionary category in the budget. They pledged to reform entitlement programs like Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, but rural Republican voters repeatedly rejected such reforms because they depend on those programs. Each time Republican members of Congress stepped away from the issue to save their political hide.

Many conservative members of Congress protest the social spending programs that crowd out other priorities. In 2010 defense spending was over 5% of GDP, more than twice the percentage of the state and federal spending on Medicaid. Defense spending has been reduced to 3.6% of GDP and Medicaid spending has grown to 3.2% of GDP. I will leave the series and chart links in the notes. As a share of GDP, Medicare has grown from 0.5% in 1967, two years after the program was enacted, to a current level of 3.6%.

The trustees are projecting a per capita growth rate of 5.4% and the program is now almost half funded by general tax revenues. Dedicated payroll taxes and cost sharing by Medicare recipients were supposed to fund the program entirely. Democrats want to raise taxes to shore up underfunded entitlement programs they instituted last century when they had filibuster proof majorities. Republicans view these higher taxes as a moral hazard, a reward for Democrats’ excessively optimistic promises and poor planning.

Voters in rural counties form a strong Republican base but depend on state spending and taxes from urban taxpayers to support the infrastructure central to their local economies. The growing of grains and vegetables, and the raising of animals requires natural resources that include land, water and food. Highways and utility lines in sparsely populated counties connect farmers and ranchers to their markets. Despite gains in efficiency, the farming and ranching industries are less efficient than industrial production. Crops and animals do not pay taxes. People do.

Elected officials must play a game with their constituents. Politicians in state legislatures could enact a head tax on dairy cows and beef cattle to cover the cost of those direct and indirect costs. Federal officials could enact a pollution tax on cattle and chickens whose concentrated effluent contaminates interstate waters. However, such taxes would raise the prices of milk and beef in grocery stores. Officials are hesitant to enact specific taxes like that because such taxes arouse voter anger and risk a politician’s career. Lawmakers prefer to fund such costs with general tax revenues. The costs appear as line items on a state or federal budget that is hundreds or thousands of pages long and disappear in the thicket of words.

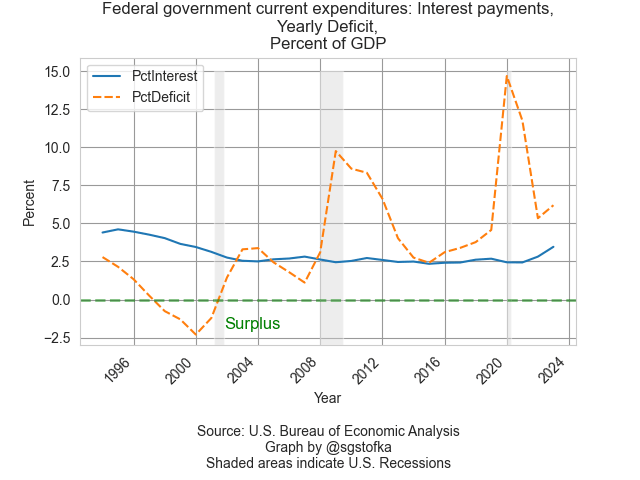

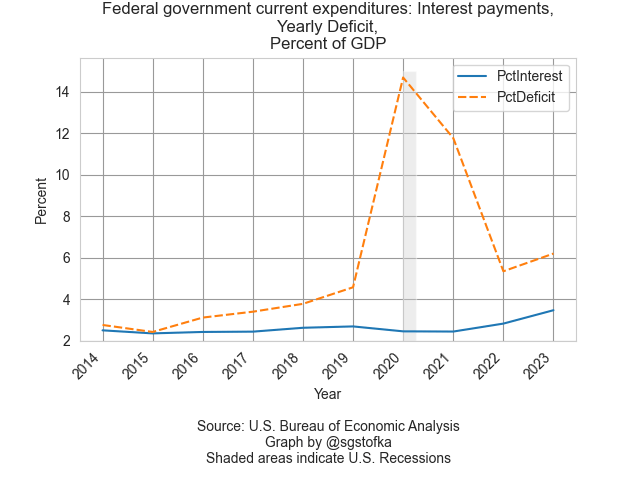

The private economy is not capable of supporting the current social and defense spending at this level of taxation. Neither political party wants to compromise on their priorities and the interest expense on the debt will grow, exacerbating the tensions between both political parties. That interest is now 3.5% of GDP, about the same as defense and Medicare spending. That interest is entirely funded by a deficit. We are borrowing to pay the interest on the debt we have accumulated.

The blue line will continue to rise, pushing the orange line upward as well. The political parties will stay entrenched in their ideological bunkers, creating a daily drama covered by mainstream and social media whose coverage incentivizes posturing rather than compromise. Just as Britain did in the inter-war period a century ago, we are steadily losing resilience, ready to falter at the next crisis.

////////////

Photo by British Library on Unsplash

Notes on social programs: Defense spending is series FDEFX at the FRED database. Medicaid is series W729RC1. Medicare is W824RC1. Each series link is a percentage of GDP.