June 2, 2024

by Stephen Stofka

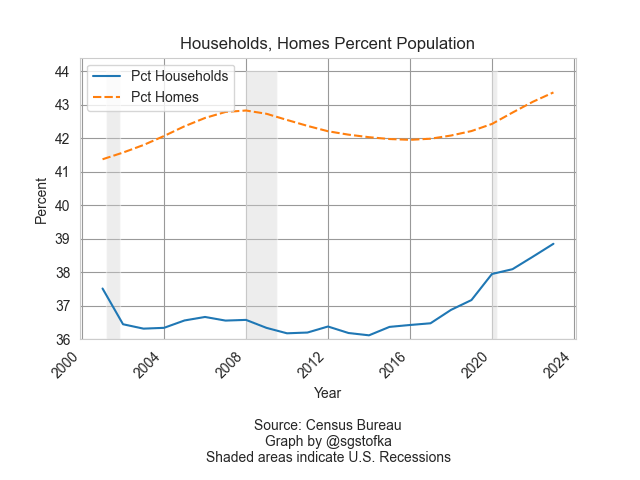

This week’s letter continues a topic from last week, our expectations of inflation. The high inflation of the 1970s prompted a lot of debate on this topic, and I will try to cover a portion of those ideas. Hypotheses regarding the formation of expectations influence monetary policy and the manner in which the Fed raises interest rates. Different policy approaches reach across the country into the pocketbooks of many Americans. They can mean the loss of many jobs or few jobs, or the viability of buying a home.

The University of Michigan conducts a monthly survey of consumer sentiment in a rotating sample among 500 participants. Respondents are asked to estimate the rate of inflation for the next twelve months (see here, p. 5). Inflation is a rise in the average price of all goods but in casual conversation, we often use the term loosely to refer to a rise in prices of the goods and services that have the most impact on our lives. Each of our estimates are biased but an average of many estimates should approximate a comprehensive survey of the prices of many goods. This BBC five-minute video explains this phenomenon known as The Wisdom of the Crowd when many people try to estimate the number of jelly beans in a mason jar.

The blue line in the graph below is the headline CPI that tracks a basket of goods and excludes expenses like the employer portion of health care insurance. The Fed pays more attention to the PCEPI, the green line in the graph below. That methodology is based on actual expenditures in various sectors of the economy, including employer paid health insurance. Notice how closely the average estimates of inflation approximate this broad measure of price movement. In the April 2024 survey, expectations averaged 3.2%, a big decrease from over 5% in 2022 but a slight rise from 2.9% in March.

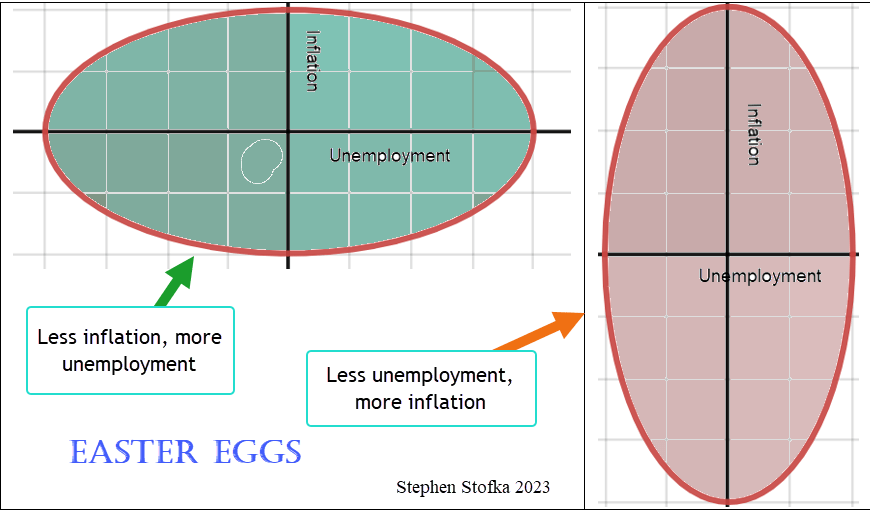

How do we form inflation expectations? There are two hypotheses, and they are distinguished by how errors occur in our expectations. Adaptive expectations was a predominant hypothesis until the 1970s. It holds that we revise our forecasts up when actual inflation is higher than we expected, and down when inflation data indicates that our forecast was too high (Blanchard, 2017). Imagine that we are offered a discount at the doctor’s office if we guess our weight within three pounds. We base our guess on a previous weight reading. If it is too low, we lose our discount so the next time we revise our guess higher. Under this hypothesis, our expectations are very much guided by past experience and our forecast errors are systemic. To tame high inflation, monetary policy must act like a shock that induces a recession and alters the expectations of investors and consumers.

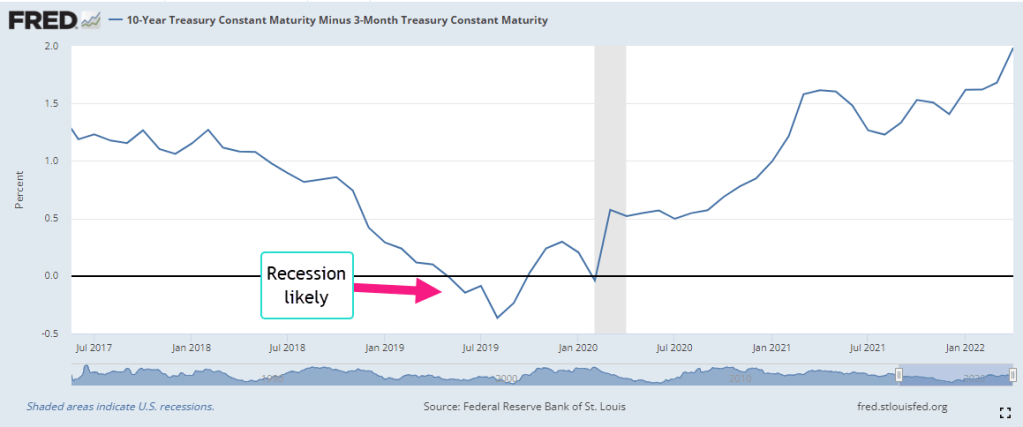

In August 1979, during the Carter administration, Paul Volker assumed the position of Fed chair. In October, the Fed raised interest rates 1.5%, then lowered by a half-percent in November, then raised them again by a half-percent in December. In those three months, sales of new one-family homes (HSN1F) dropped 25%. A few months later, in the spring of 1980, came another interest rate shock of a 3.5% increase over two months and new one-family homes sank by 38%. They did not begin to recover until the spring of 1982. This cattle prod approach to taming expectations was influenced by the adaptive expectations hypothesis.

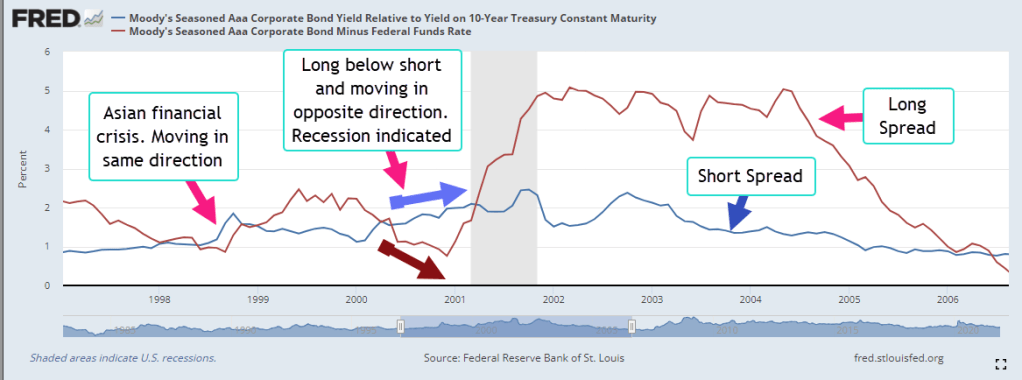

Statistical tests done in the early to mid-1970s showed that we paid much more attention to ongoing conditions than previously thought. This contradicted the notion that our expectations relied mostly on past experience. Two economists, Robert Lucas and Thomas Sargent presented a rational expectations hypothesis claiming that we form the best inflation forecast we can with the information available to us. Rational does not mean perfect. Errors in our forecasts are random and arise from unseen shocks (Humphrey, 1985). The critique against this hypothesis was that people were too naïve or uninformed to form rational expectations. Information frictions blurred the distinction between rational and non-rational (Angeletos et al, 2021).

Over the past several decades, the rational expectations hypothesis has guided policymaking at the Fed. If the Fed presents a convincing policy commitment to steer inflation toward a particular target, investors will change their behavior in accordance with their belief in the Fed’s commitment. Economist Roger Farmer (2010) has called them self-fulfilling beliefs and devotes a section of his book to rational expectations. Under this regime, the Fed uses steady, incremental rate increases and consistent policy statements to “corral” expectations like a trained sheepdog persistently badgering a flock of sheep to guide them into a holding area. By guiding expectations, monetary policy can tame high inflation without necessarily producing a recession. This has been dubbed a soft landing.

In the spring of 2022, the Fed under Chairman Jerome Powell raised rates a half percent a month, a steady rate to let everyone know that the Fed was serious. From the spring of 2022, the number of new one-family homes did not fall. That was the rational expectations hypothesis at work. The Federal Reserve as sheepdog. As with any comparison, there are a number of other factors. My point here is that ideas about people’s motivations and behavior make a concrete difference in the lives of ordinary people.

We respond to high inflation with behavior that can exacerbate inflation. Next week I will look at several scenarios that illustrate why the Fed is concerned about managing consumer and investor expectations.

///////////////////

Photo by Hassaan Here on Unsplash

Keywords: housing, interest rates, monetary policy, adaptive expectations, rational expectations, inflation

Angeletos, G.-M., Huo, Z., & Sastry, K. A. (2021). Imperfect macroeconomic expectations: Evidence and theory. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 35, 1–86. https://doi.org/10.1086/712313

Blanchard, O. (2017). Macroeconomics (Seventh ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education. p. 337. This is an intermediate economics textbook.

Farmer, R. E. A. (2010). How the economy works: Confidence, crashes and self-fulfilling prophecies. Oxford University Press. This book contains succinct descriptions of various economic theories that have influenced policy and is aimed toward the general reader.

Humphrey, Thomas M., The Early History of the Phillips Curve (1985). Economic Review, vol. 71, no. 5, September/October 1985, pp. 17-24, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2118883