September 4, 2016

The market seems awfully quiet leading into September, a month that is the most consistently negative for the past century. LPLResearch notes that it has been about 35 years since the market was this quiet for this long. It has been 30 trading days (at the end of August) since the SP500 had strayed more than 1% from its 10 day average. A year ago in August 2015 the market spent 17 trading days in this quiet zone then fell 6% in 3 days. In September 2014, the market acted like a sailing ship in the horse latitudes before sinking 6% over the following ten days. We wish the market went up after these long quiet periods, but the trend is usually down.

Investment

Let’s look at a disturbing long term trend – a decline in private investment in housing (residential), as well as factories, equipment and office buildings (non-residential). What is private? Non-government, i.e. companies and individuals in the private market.

First, let’s look at private investment as a whole before we look at the parts. As a percent of GDP, we are near post-WW2 lows.

“Oh, that was the housing bubble and financial crisis,” we might say. Everytime we think we’ve got it figured out, that is the beginning of the journey of learning, some Zen master probably said at some time. Be humble, little tree frog, or wax on, wax off. Something like that.

Only this year has the economy surpassed the 2008 level of inflation adjusted private investment. To get a sense of the damage done by the financial and housing crisis, the chart below is a rolling 5 year sum of investment and covers most of the post-WW2 period. Look at the historic dip – not a pause, not a flattening, but a genuine crater in investment growth. Here we can see the over-investment during the tech bubble of the late nineties when the 5 year sum climbed at a 60 degree angle, followed by the 45 degree climb as the housing bubble climaxed. Even scarier is the possibility that we may still be above the growth trend of the 70s, 80s and early 90s – that there is still a bit of correction left.

Housing Investment

Seven years after the official end of the recession, ten years after the height of the housing bubble, investment in residential housing is still near all time lows. As a percent of the economy (GDP) it has been rising but from a great depth.

Slow household formation after the financial crisis, i.e. Johnny and Mary staying home or moving back in with Mom and Dad, has contributed to the slow recovery in housing investment. The millennial generation, bigger in numbers than the aging Boomers, doesn’t have the same preference for owning their own home. Census Bureau data shows that the home ownership rate in the under-35 crowd has declined from 39% in 2010 to 34% in 2016. While it may be more noticeable in the millennial aged cohort, the data shows a decline in all age groups, and across incomes (page 10). Competition for a dwindling stock of apartment rentals has caused a sharp rise in median rental rates across the country.

Why a dwindling number of rental units? As home ownership rose in the 2000s, the investments in new apartment building began to decline in 2007, then fell abruptly during the crisis. Only in 2011 did it finally start to rise up from its trough. The drop in investment was so huge that just posting a number doesn’t do it justice. Millennials are now being squeezed by a lack of rental housing stock. Sharply rising home values in popular areas like Denver make it more difficult for millennials to shift preferences to home ownership.

The business Side

Now let’s look at investments in office buildings, equipment and factories. These can be somewhat cyclical but the long term trend is down. Since China was admitted to the WTO in 2001, the highs in the cycle have been trending lower. During the 2000s Americans were not saving enough to fund business investment growth and our economy increasingly relied on foreign investment dollars. Today we are on the decline in that investment cycle and we can expect further declines.

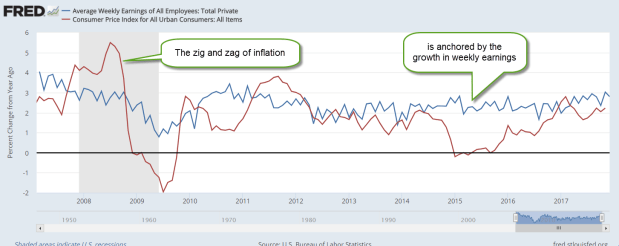

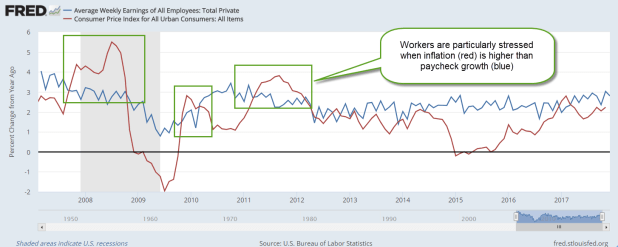

Does low inflation hurt investment?

It makes sense that a stable environment of low inflation should encourage business investment. Low interest rates should encourage lending to business, etc. This is the conventional narrative that has guided policy making at the Federal Reserve. Stop an economist on the street and ask them if low interest rates encourage business investment and they will probably say yes. Here’s a quote from an economics course “If the expected rate of return [on the new investment] is greater than the real interest rate, the investment makes sense.”

Makes sense but what if it is partially wrong? Is it possible that low interest rates could, in some cases, discourage investment? This is the opposite of the conventional narrative but let’s walk this path for a bit. We often think of interest rates as a dependent variable, a response to something indicating a demand for money. What if it is also an independent variable, a cause affecting the demand for money? Yep, it’s one of those interdependent cyclic things that might make you want to meditate on the universality of love and being, but stay with me 🙂

Interest rates can be a heuristic for investors, a signal of the demand for money, a weather vane of the underlying strength of the economy as seen by the top economists in the country, the folks at the Federal Reserve. Low rates could be seen as a cautionary warning to investors. If the economy were really getting stronger, would interest rates remain low? Of course not, an investor might reason. They would rise in response to stronger demand for money. But they are not rising so better to be cautious, the investor reasons. The dog chases its tail.

Do low interest rates cause reckless borrowing?

Are low interest rates prompting companies to borrow excessively? Well, yes and no. Yes, they are borrowing more but the growth trajectory, the rate of growth, is about the same as it has been since 1990. As we can see in the chart below, each recession is a pause in the growth of corporate debt. After each recession, the level rises again on approximately the same slope. The “pause” in this last recession lasted a whopping four years, during which corporate debt declined as much as $600 billion, or about 5.6%.

The problem is what they are borrowing it for. Companies typically buy back their own shares at their hghest, not lowest value. By lowering the number of shares outstanding, buybacks raise the earnings per share even if there is no real growth in earnings. Instead of buying low, selling high, companies tend to buy high, sell low. FactSet gathers and crunches a lot of market data. Their mid-year analysis of share buybacks shows that total dollars spent on buybacks is approaching the highs of 2007. Investment in real growth, in productive plants, equipment and office buildings, has declined the past three quarters but share buybacks, the appearance of growth, have increased.

A simple example

How could low inflation hurt investment? If predicted inflation is rather low, about 2%, sales growth will not get that extra kick from inflation. Let’s say that a company’s sales are $1000 and the owners have an extra $50 to invest. They are considering a plan to invest $50 and borrow $50 from the bank to expand in the hopes of making more sales.

First they consider the return by not expanding. They put their $50 in the bank and make 2% interest or $1. At 2% inflation, $1000 sales grows to $1020. Let’s say that the company has a 30% gross margin, which gives an extra $6 profit on the extra $20 in sales. The combined extra return to the owners is $7, a $6 profit and $1 in interest income.

Then they consider a second scenario. Let’s say that the interest rate on the borrowed money is 6%, or 4% above the inflation rate of 2%. As in the first scenario, they assume that the savings rate, or opportunity cost, of the invested $50 is about 2%. The owners can expect an extra $4 imputed and actual cost on that combined $100 of investment. If inflation is averaging 2% per year, then they can expect sales of $1020 even if there is no real sales growth. Again, they use a 30% gross margin to arrive at an extra profit to them of $6, the same as the first scenario. If the extra investment does not produce any real sales growth, then the owners will net an extra profit of about $2, much less than the scenario of no expansion. To make the same extra profit as in the first scenario, the owners need to generate an extra $11 in profit. Minus the $4 in costs, the extra profit will be $7, the same as the first scenario. Note that the owners are now trying to break even with the extra profits of not expanding. To do that they must have sales of about $1037, or almost 2% real sales growth in addition to the 2% inflation growth.

Now, let’s consider a higher inflation rate of 4%. Let’s imagine that the cost to borrow money is 8%, or 4% higher than inflation, as before, so that the cost of borrowing the $50 for a year is $4. As before, we’ll assume that the savings rate, or opportunity cost, of the $50 from the owner’ pockets is the same as inflation, or 4%, so that the imputed cost of the owners’ investment is $2. Borrowed and imputed cost of the extra $100 invested in the company is now $6. If there is no real sales growth, total sales will now be $1040, or $40 more. A 30% margin gives a gross profit of $12, leaving the owners with about $6 extra profit on investment.

Note that a doubling of the inflation rate in this scenario has produced a tripling of extra profit even with no real sales growth. Still the extra profits are less than not expanding at all. They must still have a real increase in sales, but it is very small.

So a stable higher inflation rate and interest rate encourages business investment. The key word here is stable. We could keep doing this calculation with higher and higher rates producing more net profits to the owners but…. As inflation gets higher, it becomes less stable, less predictable and this unpredictability actually hurts business investment.

The Federal Reserve has set a target inflation rate of 2%. I think it is too low and the lackluster growth of the economy seems to bear that out. Since the 1970s, prominent economists (Taylor and Tobin, for example) have suggested alternative targets that the Federal Reserve could use to replace the “dual mandate” set by the Congress in 1977.

A prominent alternative is a growth target in nominal GDP, called NGDP, There are several variations but the one most favored has been level targeting, the calculation of GDP targets over the following five years or so based on an agreed growth rate. The Fed would then take action to offset deviations from those targets. Two prominent economists, Robert Hall and Greg Mankiw, wrote a paper in 1993 explaining these alternative targets and the policy tools that the Federal Reserve could employ to help reach those targets. During the period called the “Great Moderation,” from 1985-2007 national income grew at a rate just a bit more than 5%.

Hall and Mankiw noted (pg. 5) that the consensus among macroeconomists at that time was in favor of a targeting of nominal national income because it was a transparent measure, a clear, simple target. The authors commented (pg. 4): “A rule like ‘Keep employment stable in the short run but prevent inflation in the long run’ [the current rule, by the way] has proven to be hopelessly vague; a central bank can rationalize almost any policy position with that rule.”

So the idea of nominal income or production targeting is familiar to economists and policymakers for several decades but has never been adopted. We can only assume, as the Nobel winner James Buchanan posited, that there is a very good reason for that. When an obscure policy remains in place, it does so for a reason. Enough policymakers want the obscurity that the policy provides. I’m reminded of a letter John Adams wrote to Jefferson lamenting some of the vague language used in the Constitution which both of them had helped to craft. Adams noted that the vagueness was necessary to reach consensus at the Constitutional Convention. Efforts to achieve more precision in language or attempts to add specific detail were sometimes met with hardened disagreement. The “general Welfare” wording of the tax and spending clause, Section 8, was one example. Some argued that the lack of precision would give future generations of lawmakers some flexibility in determining what, in fact, was the general welfare of the United States.

Whatever the Fed is doing now is only partially working and a different approach might be in order. The use of the Labor Market Conditions Index, a broad composite of over twenty employment indicators, in guiding monetary policy shows that the Fed is reaching for a broader set of guidelines. As Hall and Mankiw indicated, nominal targeting might give the Fed that broad guide, one that is less influenced by the needs and whims of elected politiciams.

Investment decline and the stock market

Let me finish on a somber note. The year over year growth rate in the SP500 and private investment have both gone negative this year, for the first time since the end of the recession in 2009. The SP500 data is copyrighted so here’s a link to that chart. Pay attention.

/////////////////////////////

Notes:

If you would like to read more on the relationship of investment to savings, check out this 2006 NBER paper.

///////////////////////////

Happy Labor Day and put a shrimp on the barbie as a toast to the summer passing!