September 8, 2024

by Stephen Stofka

This week’s letter is about the labor market, part of a series on investing. Friday’s monthly labor report indicated a job market that is cooling but still growing. Although the market reacted negatively to the news, the Fed will begin reducing interest rates at its meeting next week. The S&P 500 index, the most widely held basket of stocks, is up 15% for the year but the index has twice risen above 5500 before falling back. An index of business activity in the services sectors continues to expand but manufacturing activity is still contracting slightly. When investors get conflicting economic signals, they are responsive to negative data points more than positive ones. The approach of what may be a contentious election creates an environment where investors are more likely to protect their portfolio value and exit short-term positions. Let’s now turn to long-term trends in the labor market.

Economists at the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) refer to workers aged 25 -54 as the core work force. To save some typing, I will refer to this age demographic as the “core.” During those thirty years we accumulate stuff while we build our careers. We buy cars, furniture, homes and vacations. We build retirement savings for ourselves and college funds for our kids. The core is the nexus of a growing economy.

This coming Wednesday we will remember 9-11 and the 3,000 civilian lives lost in the attack on the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan. Since that time, there has been little investment in those workers who form the core of the labor market. From August 2001 to August 2024, the economy has added less than seven million jobs in that age demographic, an annual growth rate of just 0.28% (See FRED Series LNS12000060).

As you can see in the chart above, most of the growth in the core has occurred during the Biden administration. The surge in employment in this age group led to growing incomes and greater purchasing power in an age group that is in the accumulation phase of its lifetime. That rapid growth in employment, coupled with pandemic recovery payments from the government were strong contributors to the rise in inflation in the 2021 – 2023 period. Voter sentiment in this age group focused on the inflation, not the job growth, demonstrating again that we pay more attention to negative rather than positive news.

Several factors contributed to the plateauing of job growth in the core. Demographics played some part. Population analysts have assigned a span of about 18 years to each generation so that the thirty-year span of the core labor force encompasses two and sometimes three generations. The first of the large post-war Boomer generation turned 54 in 2000. As the Boomers aged out of the core, a smaller Generation X, born 1964 to 1982, became the dominant component of this age group. In 2013, the first Millennials, a generation larger than the Boomers, joined the core, and in 2016, the last of the Boomers aged out of the core.

A few months after 9-11, China was admitted to the World Trade Organization, and within a decade became the world’s factory. Investors poured capital into China, taking advantage of low labor rates and a currency whose exchange rate was maintained at a low level by the Chinese central bank. Investors from outside China got more bank for their buck. As investment moved to China, many production facilities in the U.S. shuttered their doors. In the seven-year span between China’s admittance to the WTO and the start of the financial crisis in September 2008, manufacturing employment (see FRED Series MANEMP) fell by a fifth. By January 2010, employment in the manufacturing sector had declined by a third.

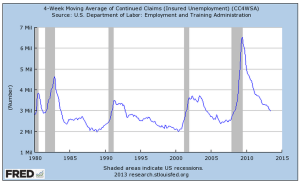

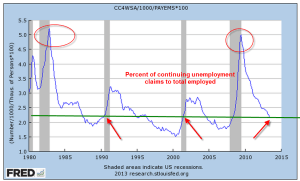

During the 2000s, low interest rates fed a frenzy in home financing and produced a bubble in the U.S. real estate market that imploded in 2008. The resulting financial crisis affected assets and financial institutions around the world. Millions of Americans lost their jobs. From the start of 2008 until the end of 2009, the core work force fell by 6%, about six million jobs. In 2018, an interval of ten years, the level of employment in this age group finally rose above its 2008 level.

Instead of vigorously promoting policies that encouraged job growth, the Obama administration offered policies to support families suffering from the lack of job growth. Democratic politicians eagerly passed ambitious social programs but faltered when implementing policy solutions that embodied their legislative goals. In Recoding America, Jennifer Pahlka (p. 125) recounts the efforts to fix healthcare.gov, the bungled rollout of the health exchanges created under the Affordable Care Act known as Obamacare. In The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order, Gary Gerstle (p. 226) notes that the Obama administration focused more effort and political capital on providing healthcare insurance for poor people rather than supporting the 9 million households in danger of losing their homes to foreclosure.

A sense of betrayal soured voter sentiment and helped to support the emergence of the Tea Party in the 2010 election and the MAGA voters who supported Donald Trump’s candidacy in the 2016 election. In 1976, voters punished President Gerald Ford for pardoning Richard Nixon. In the 2016 election, voters punished Hillary Clinton as a symbol of a set of values disloyal to many Americans. Donald Trump promised to bring manufacturing jobs back to America by taxing Chinese imports and cutting corporate taxes. In the first three years after the 2008-2009 recession, manufacturing employment under Obama grew by more than it did in the first three years of the Trump presidency (see notes for details). No amount of political rhetoric can overcome the power of a supply chain now firmly anchored in Asia.

Biden’s infrastructure policies have actively promoted job growth in the core. Can the economy sustain such growth in this acquisitive age group while keeping inflation at a reasonable level? Should the Fed raises its target interest rate from 2% to 3% to accommodate job growth that supports people when they are raising families and building careers? I think so. Should Harris win November’s election, she should adopt Biden’s pro-growth policies. Should Trump regain office in the coming year, he will try to use tariffs to shift the nexus of the global supply network from Asia back to the U.S. That policy will only increase prices and help maintain a higher level of inflation without promoting the economic growth that supports households in their middle years.

///////////////

Photo by Tim Mossholder on Unsplash

Manufacturing employment notes: From January 2010 to December 2012 manufacturing gained 500,000 jobs, an increase of 4.4%. From January 2017 to December 2019, the manufacturing sector gained 432,000 jobs, an increase of 3.5%. In January 2010, manufacturing employment was near a low, continuing to fall after the official end of the recession in July 2009.

Keywords: Obamacare, inflation, labor, financial crisis, China, manufacturing, infrastructure