September 24, 2023

by Stephen Stofka

This week’s letter is about labor productivity. The autoworker’s union (UAW) expanded its strike to 38 parts and distribution plants in the hopes that a wider impact will incentivize further concessions from auto executives. Labor constitutes only 10-15% of the price of a car yet labor disputes may give the impression that rising car prices are entirely or mostly the fault of labor union demand.

For more than 100 years, auto plants of the Big Three automakers have been union shops. Foreign manufacturers like Toyota and Honda have built non-union plants in southern states where union organizers have less influence with policymakers. There are almost a million auto workers now in Mexico where wages have been lower. In 2022, GM Mexico paid its workers between $9.15 and $33.74 an hour, but relatively few auto workers in Mexico make more than $16 per hour.

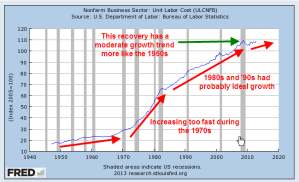

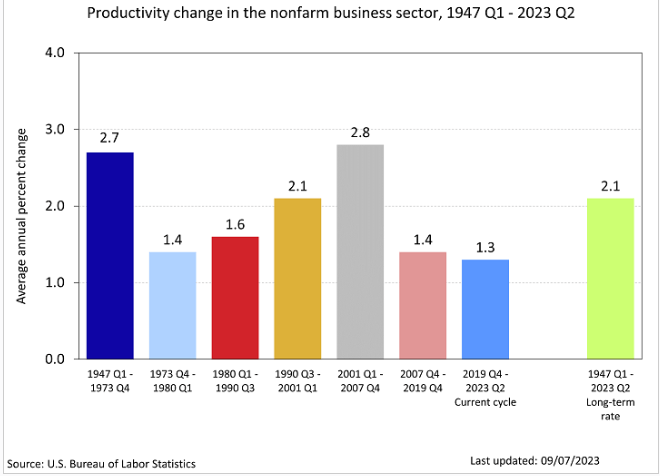

Two weeks ago, the BLS released their productivity figures for the second quarter. Productivity rose faster than labor costs by a good margin – notching a 3.5% annualized gain versus a 2.2% increase in unit labor costs. The manufacturing sector that car manufacturers belong to had a lower productivity gain of 2.9%. In that productivity release the BLS provided a chart grouping productivity gains by decade. The 75-year average is a 2.1% annual growth rate.

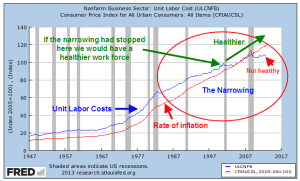

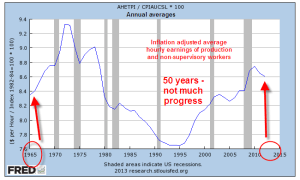

An often repeated theme of union workers and workers in general is that wage gains have not kept up with productivity gains. The BLS charted both series since 1973 and the divergence keeps growing by decade. American workers are competing with lower wage workers in Mexico, China and southeast Asia.

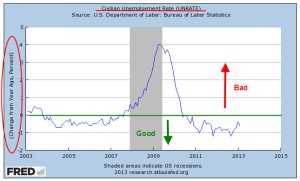

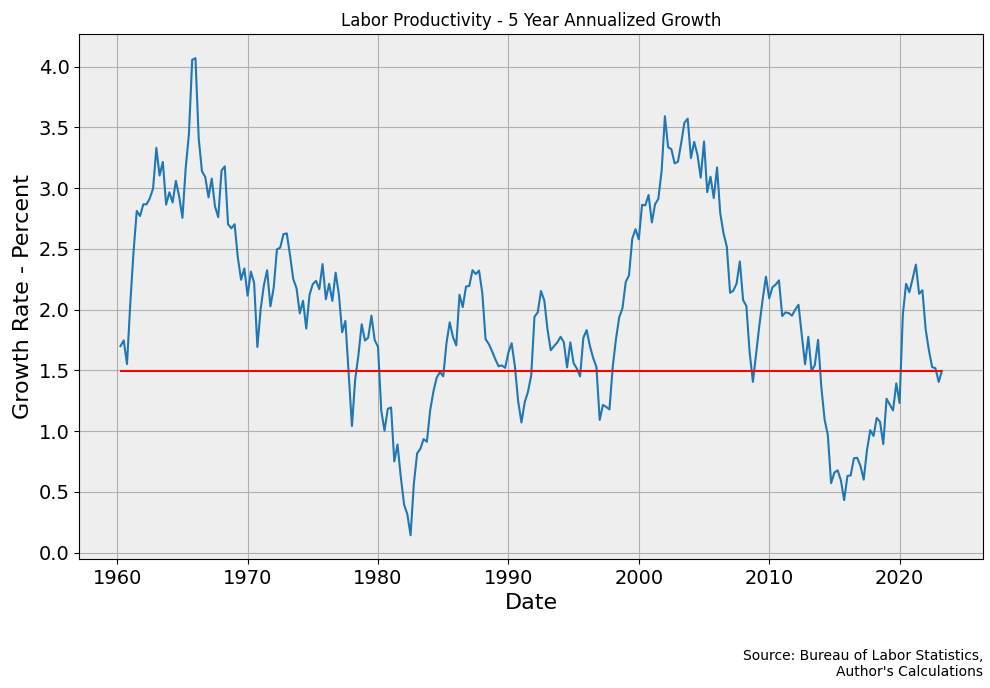

The annual gain in Productivity is erratic, rising sharply at the onset of recessions when workers are let go and the total hours worked declines. Recessions reduce the percentage of hours worked far more than the percentage reduction in output. I charted the annual gain in Labor Productivity (FRED Series OPHNFB) to show the effect of these shocks. The pandemic caused a particularly sharp rise and fall, as shown in the red rectangle below.

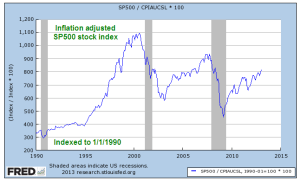

A five-year chart smooths out the divergences, letting us see the patterns more clearly. The red line in the graph below is the 1.5% current growth rate.

Trends in productivity growth are a medium term process, longer than any Presidential term. Despite that, candidates promise big productivity gains if they are elected. Republican candidates promise that lower taxes will boost productivity because that claim appeals to Republican voters. When productivity growth declined following the Bush tax cuts in 2001, conservatives blamed the stifling effects of regulatory compliance and called for more tax cuts. Democratic politicians promise more subsidies to an industry that is not nimble enough to respond to changing economic circumstances.

There are many factors that contribute to productivity growth. Some economists claimed that lower interest rates after the financial crisis would raise productivity. It fell. Those believers assert that declining productivity growth would have been worse without lower interest rates. This claim also cannot be disproved. Hypothetical situations are the favorite shield of a believer.

Corporate profits are up sharply since the start of the pandemic. For the past year, GM has enjoyed strong profit growth but they have had far too many down quarters since the financial crisis. Ford has fared better but its profit margin of 2.4% is only slightly more than the high-volume, low margin grocery giant Kroger. Stellantis has struggled to make a profit since 2018. For decades, federal and state governments have subsidized these auto giants with tax breaks and loans because the industry as a whole employs 1.7 million workers and contributes more than 10% to GDP. It is an industry where politics and economics are tightly intertwined. The politics clouds the economic analysis and the economics contorts the political calculations.

///////////////

20230924AssemblyLine

Photo by carlos aranda on Unsplash

Keywords: auto industry, GM, Ford, Stellantis, union, UAW, labor, workers, wages