May 5, 2019

by Steve Stofka

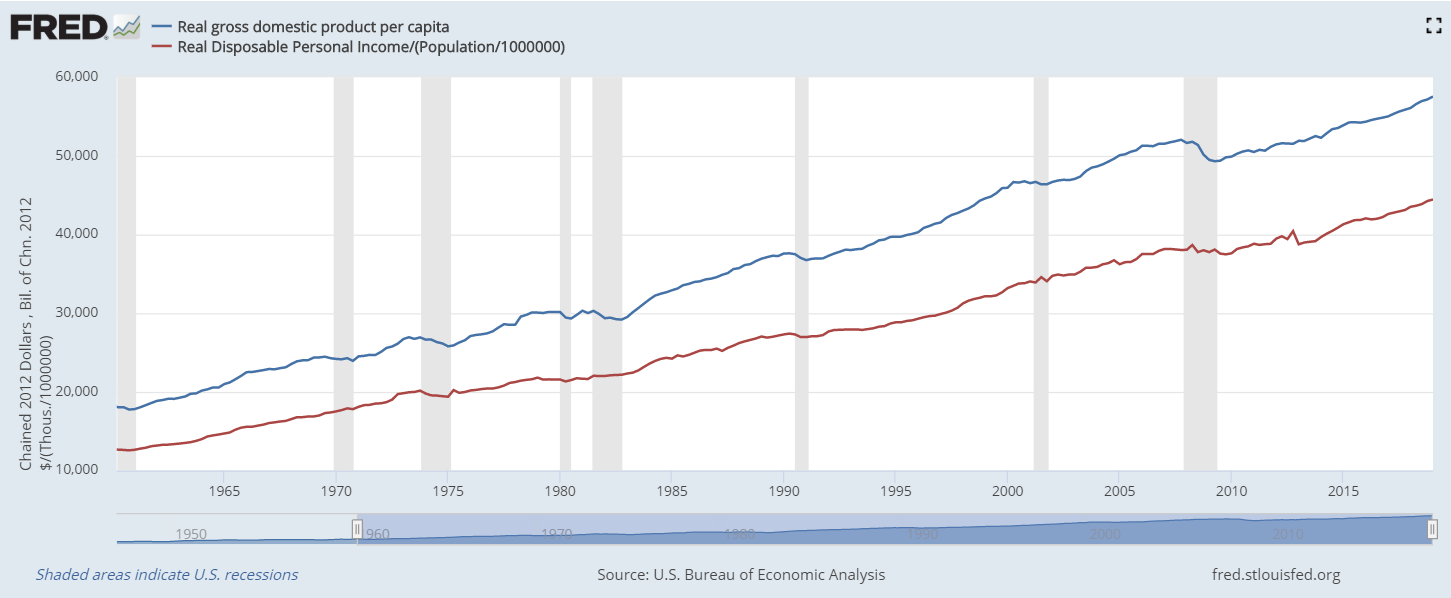

This week I’ll review several decades of trends in productivity. How much output do we get out of labor, land, and capital inputs? Capital can include new equipment, computers, buildings, etc. In the graph below, the blue line is real GDP (output) per person. The red line is disposable (after-tax) income per person. That’s the labor share of that output after taxes.

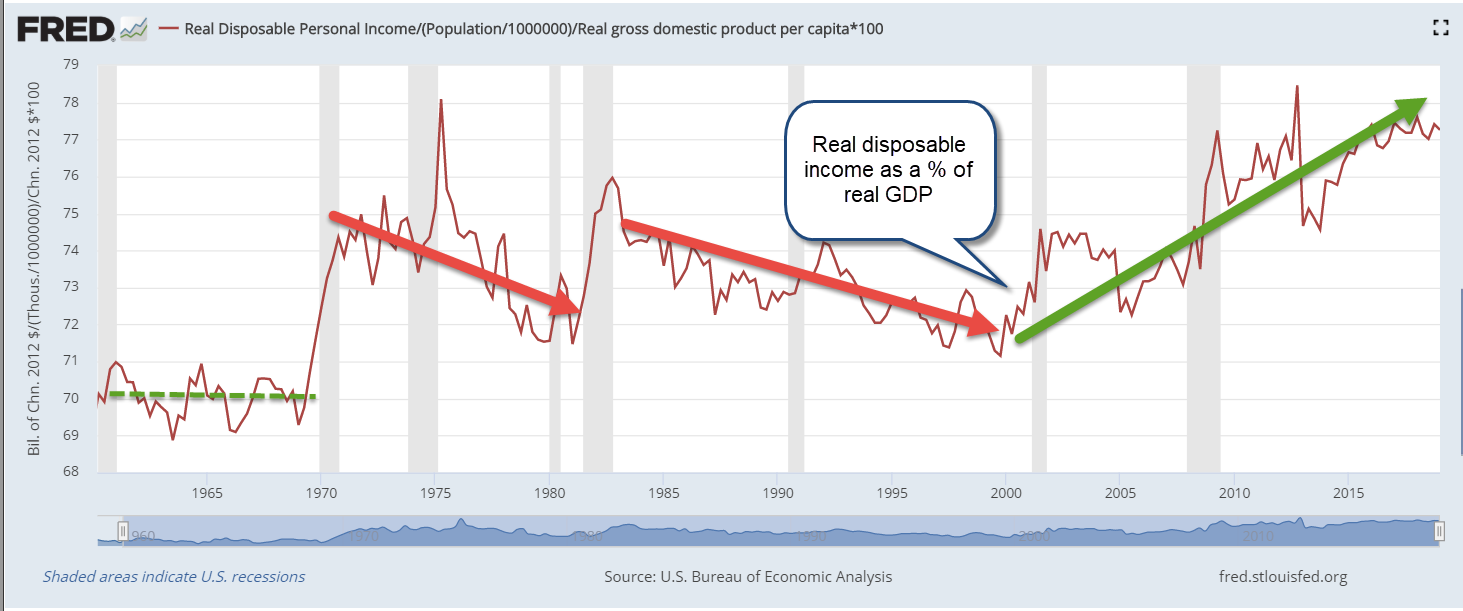

As you can see, labor is the majority input. In the following graph is the share of real GDP going to disposable income. In the past two decades, labor has been getting a larger share.

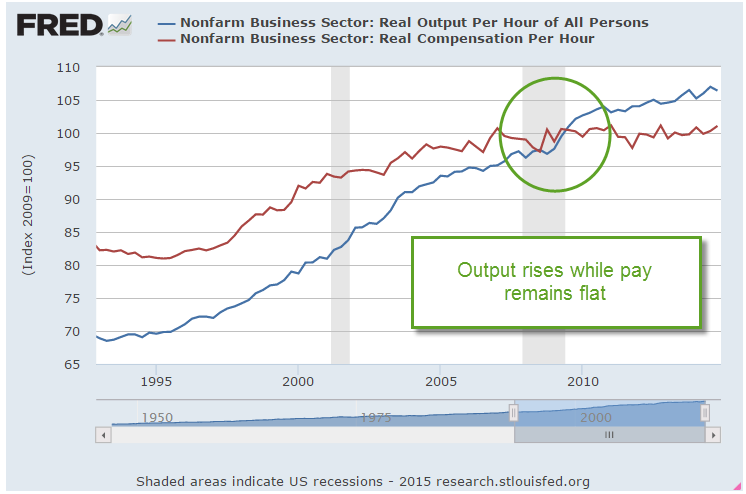

That might look good but it’s not. Since 2000, the economy has shifted toward service industries where labor does not produce as much GDP per hour. The chart below shows the efficiency of labor, or how much GDP is being produced by labor.

If labor were being underpaid, the amount of GDP produced per dollar of disposable income would be higher, not lower. On average, service jobs do not have as much leverage as manufacturing jobs.

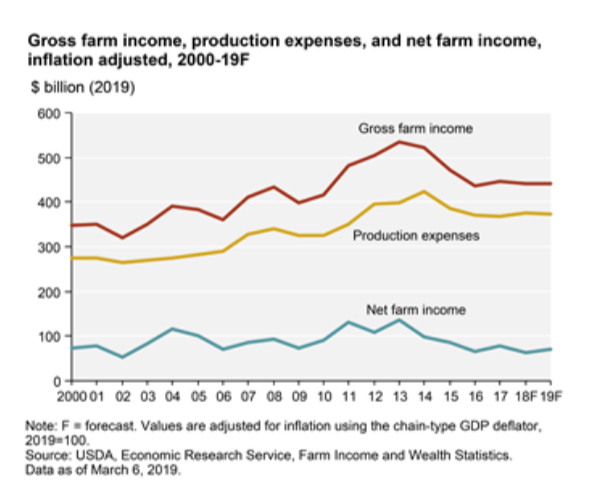

A century ago, agricultural jobs were inefficient in comparison to manufacturing jobs. The share of labor to total output was high. In the past seventy years, the agricultural industry has transformed. Today’s farms resemble large outdoor manufacturing plants without walls and productivity continues to grow. In the past five years, steep price declines in the prices of many agricultural products have put extraordinary pressures on today’s smaller farmers. The increased productivity of larger farms has allowed them to maintain real net farm income at the same level as twenty years ago (Note #1). Here’s a graph from the USDA.

Although agriculture related industries contribute more than 5% of the nation’s GDP, farm output is only 1% of the nation’s total output. The productivity gains in agriculture have not been shared by the rest of the economy. Labor productivity has plunged from 2.8% annual growth in the years 2000-2007 to 1.3% in the past eleven years (Note #2). Here’s an earlier report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics with a chart that illustrates the trends (Note #3). The report notes “Sluggish productivity growth has implications for worker compensation. As stated earlier, real hourly compensation growth depends upon gains in labor productivity.”

Productivity growth in this past decade is comparable to the two years of deep recession, high unemployment and sky-high interest rates in the early 1980s. The report notes “although both hours and output grew at below-average rates during this cycle [2008 through 2016], the fact that output grew notably slower than its historical average is what yields the historically low labor productivity growth.” Today we have low unemployment and very low interest rates – the exact opposite of that earlier period. Why do the two periods have similar productivity gains? It’s a head scratcher.

Simple answers? No, but hats off to Donald Trump who has called attention to the need for a greater shift to manufacturing in the U.S. economy. He and then Wisconsin governor Scott Walker negotiated with FoxConn Chairman Terry Gou to get a huge factory built in Mount Pleasant, Wisconsin to manufacture LCD displays, but progress has slowed. An article this week in the Wall St. Journal exposed the tensions that erupt among residents of an area which has made a major commitment to economic growth (Note #4).

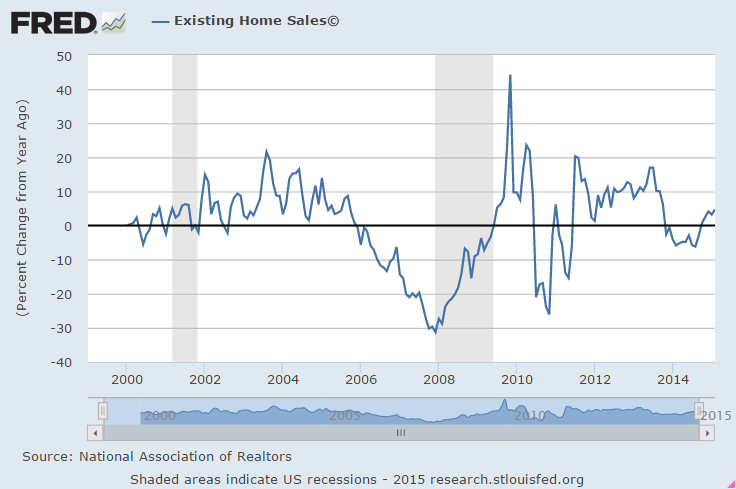

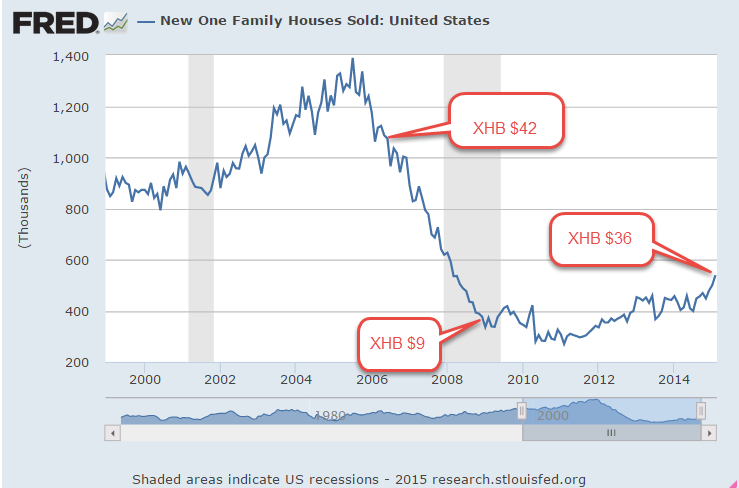

If we don’t shift toward more manufacturing, American economic growth will slow to match that of the Eurozone. Along with that will come negative interest rates from the central bank and little or no interest on CDs and savings accounts. We already had a taste of that for several years after the recession. No thanks. Low interest rates are a hidden tax on savers. They lower the amount of interest the government pays at the expense of individuals who are saving for education or retirement. Interest income not received is a reduction in disposable income and has the same effect as a tax. Low interest rates encourage an unhealthy growth in corporate debt and drive up both stock and housing prices.

///////////////////

Note: