CWPI (Formerly CWI)

The Constant Weighted Purchasing Index (CWPI) that I introduced last summer was designed to be an early or timely warning system of weakening elements of the economy. It is based on a 2003 study by economist Rolando Pelaez on the monthly Manufacturing Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) published by the Institute for Supply Management (ISM). ISM also produces a Non-Manufacturing index for service industries each month but this was not included in the 2003 study.

The CWPI focuses on five factors published by ISM: employment, new orders, pricing, inventory levels and the timeliness of supplier deliveries.

The CWPI assigns constant weights to the components of both indexes, then combines both of these indexes into a composite, giving more weight to the services sector since it is a larger part of the economy. Both the CWPI and PMI are indexed so that 50 is neutral; readings above 50 indicate growth; readings below 50 indicate contraction. In previous months (here and here), I anticipated that the combined manufacturing and services sector index would move into a trough at this time before rising again in March and April of this year.

A longer term chart shows the wave like formation in this expansionary phase that began in the late summer of 2009.

February’s ISM manufacturing index climbed slightly but the non-manufacturing, or services, index slid precipitously, more than offsetting the rise in manufacturing. Particularly notable was the huge 9% decline in services employment, from strong growth to contraction. The service sector portion of the CWPI shows a contraction which some blame on the weather. A slight contraction – a reading just below 50 – can be just noise in the survey data. The past two times when the employment component of the services sector has dropped below 48, as it did in this latest report, the economy was already in recession; we just didn’t know it till months later.

A close comparison of the current data with the previous two episodes may sound a cautionary tone. At this month’s reading of 48.6, the CWPI services portion is not showing as severe a contraction as in April 2001 (43.5) and January 2008 (33.1), when the employment component also dropped below 48.

New orders and employment in both portions of the CWPI are given extra weight. In January 2008, new orders and employment both fell dramatically. The current decline is similar to the onset of the recession beginning in early 2001, when employment declined severely in April but new orders remained about the same. Let’s isolate just these two factors and weight them proportionate to their respective weights in the services portion of the CWPI.

Notice that the decline below 50 signaled the beginning of the past two recessions. Here’s the data in a different graph with a bit more detail.

Some cite the historically severe weather in the populous eastern half of the country as the primary cause for the decline in the services sector employment indicator and it well may be. If so, we should expect to see a rebound in this component in March. Basing a prediction on one month’s reading of one or two components of an indicator is a bit rash. However, we often mistakenly attribute weakness in some parts of the economy to temporary factors and discount their importance because they are temporary – or so we think.

In the early part of 2008, many thought that a healthy correction in an overheated housing market was responsible for the slowdown in economic growth. In the spring of that year, the bailout of bankrupt Bear Stearns, an undercapitalized investment firm which had made some bad bets in the housing market, confirmed the hypothesis that the corrective phase was nearing its end. As weakness continued into the late spring of that year, some blamed temporarily high gasoline and commodity prices for exacerbating the housing correction. In the fall of 2008, the financial crisis exploded and only then did many realize that the problems with the economy were more than temporary.

In the early part of 2001, a healthy correction to the internet boom was responsible for the slowdown – a temporary state of affairs. When the horrific events of 9-11 scarred the country’s psyche, the recession was almost over. Many were not listening to the sucking sound of manufacturing jobs leaving for China or giving enough importance to the increasing competitiveness of the global market. Employment would not reach the levels of early 2001 till the beginning of 2005.

This time the slowdown in employment and new orders in the services sector may be a temporary response to the severe winter weather. Let’s hope so.

********************************

Private Sector employment and new unemployment claims

ADP released their February employment report this week and eyes rolled. January’s benign reading of 175,000 private job gains was so at odds with the BLS’ reported gains of 113,000. “Oh, wait,” ADP said this week, “we’ve revised January’s gains down to 127,000.” In a work force of some 150 million, 50,000 jobs is rather miniscule. As the chief payroll processor in this country, ADP has touted its robust data collection from a large pool of employers. A revision of this magnitude leads one to question the robustness and reliability of their methodology, and the timeliness of their data collection. For its part, the BLS admits that its current data is based on surveys and that each month’s estimate of job gains is largely educated guesswork. ADP is actually processing the payrolls, which should reduce the amount of guesswork.

Private job gains in February were 10,000 below the consensus 150,000 but this week’s report of new unemployment claims dropped 27,000, bringing the 4 week average down a few thousand. As a percent of workers, the 4 week average of continuing claims is below the 33 year average and has been since March 2012. In this case, below average is good.

********************************

Employment – Monthly Labor Report

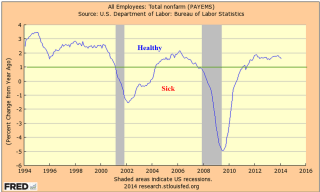

This week’s labor report from the BLS carried a banner caveat that the cold weather in February may have affected employment data. With that in mind, the headline job gains of 175K were above expectations for 150K job gains. The unemployment rate ticked up a bit. If we average the ADP job gains with the private sector job gains reported by the BLS, we get 150K plus 13K in government jobs added for a total of 163K total jobs. The year over year growth in the number of workers is above 1%, indicating a labor market healthy enough to preclude recession.

A big plus this year is the growth in the core work force, those aged 25 – 54, which finally surpassed the level at the end of the recession in the summer of 2009.

However, there are some persistent trends independent of the weather that underscore the challenges that the current labor market is struggling to overcome.

As I pointed out last week, there are several unemployment measures, from the narrowest measure – the headline unemployment rate – to wider measures which include people who are partially employed. The U-6 rate includes discouraged workers and those who are working part time jobs because they can’t find full time jobs. For a different perspective, let’s look at the ratio of the widest measure to the narrowest measure. The increase in this ratio reflects a growing disparity in the economic well being of the work force.

Contributing to the rise in this ratio is the persistently high percentage of workers who are involuntary part timers. Looking back over several decades, we can see that the unwelcome spike in this component of the work force can take a number of years to decline to average levels. Following the back to back recessions in the early 1980s, levels of involuntary part timers took 8 years to recover to average, then quickly climbed again as the economy sputtered into another recession. We are almost five years in recovery from this recession and have still not approached average.

There are more discouraged workers today than there were at the end of the recession in the summer of 2009. Discouraged workers are included in the wider measure of unemployment but not in the narrow headline unemployment figure.

The median duration of unemployment remains at levels not seen since the 1930s Depression. Someone who becomes unemployed today has a 50-50 chance of still being unemployed four months from now. That would make a good survey question: “In your lifetime, have you ever been involuntarily unemployed for four months?”

Despite all the headlines that the housing market is rebounding, the percent of the work force working in construction is barely above historic lows.

A recent report by two economists at the New York branch of the Federal Reserve paints a disappointing job picture for recent college graduates. On page 5 of their report is this telling graph of a higher percentage of recent college graduates accepting low wage jobs.

Low wage and part time jobs do not enable a graduate to pay back education loans. Almost two years ago, the total of student loans surpassed the trillion dollar mark. According to the Dept. of Education, the default rate in 2011 was 10%. I’ll bet that the current default rate is higher.

******************************

Takeaways

As is often the case, data from one source partially contradicts data from a different source. The employment decline reported by ISM bears close watching for further signs of weakness. The yearly growth in jobs reported by the BLS indicates a relatively healthy job market.