January 28, 2018

by Steve Stofka

Since the passage of the tax bill about a month ago, the stock market has risen 8%. Some people are convinced that only those at the top own stocks. Any market gains go only to the rich, they say. In the most recent of an annual Gallup survey, 54% of households reported that they directly owned stocks and stock mutual funds (Gallup). Before the financial crisis, 65% reported direct ownership of stocks.

Private and public pension plans, as well as variable annuity life insurance plans, invest a great deal in stocks. When indirect ownership is added to the mix, a whopping 80% of the stock market is owned by households (Business Insider ). The fortunes of the stock market affect most people, even those on the margins of our economy.

A quarter of companies in the SP500 have reported earnings this month. Annual earnings growth is 12% (FactSet ). In response to the new tax law, companies are bringing home their overseas cash profits and paying Federal taxes on the repatriated profits. Most are predicting strong profit growth for the coming year. Home Depot announced that they are paying bonuses to all their employees.

Since the tax law was signed, the dollar has dropped 5% against the euro. This will make U.S. exports cheaper and more attractive to overseas markets. A euro of profit earned in the Eurozone market was worth $1.07 a year ago when Donald Trump took the oath of office. That same euro is now worth $1.24. Half of the profits of SP500 companies come from overseas, and investors are betting that the dollar will not strengthen substantially in the coming year, despite Trump’s insistence that he likes a strong dollar.

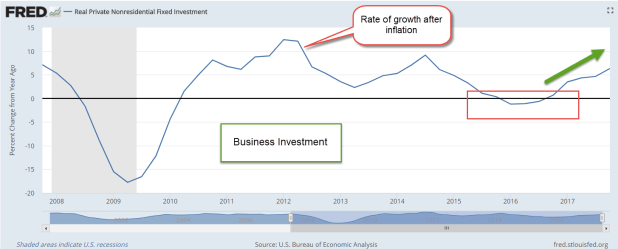

The first estimate of GDP growth, announced Friday, was 2.6%, down from the above 3% performance of the 2nd and 3rd quarters but much better than the 2% and lower rate of growth during 2015 and 2016. The growth of business investment has accelerated over the past four quarters and is nearing 7%.

Consumer spending grew by 3.8% in the final quarter of 2017, and confidence is near twenty-year highs. Accelerating business investment and a rising stock market help those on the margins of the economy. Unemployment is low. As companies struggle to find employees, they turn to those that they might have turned away a few years ago.

My checker at Target last week had a slight speech defect. A few years earlier, Target management might have put this person on some duty that did not have such frequent contact with the public, if they hired such a person at all. Unless there is a specific outreach program, many companies are reluctant to hire those with impediments when there are many able-bodied candidates to choose from. I was glad to see this twenty-something man employed.

At my local Home Depot a few weeks ago, a guy in a motorized wheelchair helped me locate an item. I got my question answered. Good for him, good for me, good for Home Depot.

A rising tide lifts all boats. Every day the ever-upward stock market convinces scores of people that they are really smart investors. Many who buy “on the dip” are rewarded as they take advantage of a short term price decline. Some who timidly stayed in cash become convinced that they were too conservative. They may listen to the market gains enjoyed by their co-workers, family and friends, and feel left out. How to catch up? They could take out a home equity loan and use the cash to buy stocks, some leveraged ETFs, or maybe some bitcoin. Some of those have been on a tear lately. Hmmmm…

Here’s the thing about a rising tide. A lot of ideas make sense while riding a good tide.