by Steve Stofka

December 10, 2017

This blog post goes to what may be a dark place for some readers. The election of Donald J. Trump may have stopped a year-long slide into recession. I didn’t start out with that conclusion. I meant to point out some interesting correlations in the velocity of money. Yeh, yawn. By the time I was done, not yawn.

If I mention the change in the velocity of money, do you groan at the prospect of a wonky economics topic? Take heart. Anyone who has slowed down from 65 MPH on a highway to 15 MPH in rush hour traffic is familiar with a change in velocity.

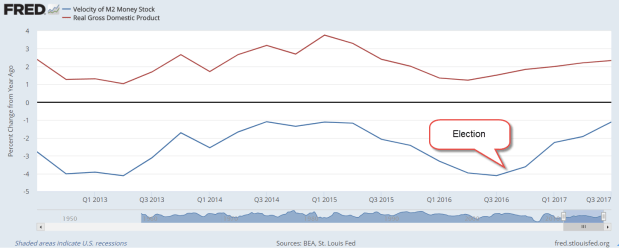

The velocity of money measures the amount of time that money stays in our pockets. It signals the willingness of buyers and sellers to make transactions. When buyers and sellers can’t agree on price, transactions fall and the change in velocity goes negative. In the chart below, the change in the velocity of money (blue line) often has a similar pattern to the change in real GDP (red line).

Both recent recessions were preceded by declines in GDP growth and the speed of money. Following the financial crisis, the Fed began to inflate the money supply in a series of policies dubbed “QE,” or Quantitative Easing. In 2011, after two rounds of QE, the Fed worried that the recovery might stall out.

Let’s turn to the green square in the chart labelled Operation Twist. Obama and a do-nothing Republican Congress were at odds so there was little chance of Congress enacting any fiscal policy to come to the economic rescue. That task was left – once again – to the Federal Reserve to use its monetary tools.

In Congressional hearings, then Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke advised the Senate Finance Committee that the short term interest rate was already zero and the Fed was out of monetary tools. The Congress should step in with a stimulative fiscal policy. The Committee members somberly hung their heads. We are incompetent, they said, so the Federal Reserve will have to rescue the country.

If it expanded the money supply further, the Fed was concerned that they would spark inflation. In hindsight, that fear was unfounded, but none of us has the luxury of making decisions while looking in the rearview mirror. Economic identities like M*V = P*Q (notes at end) are just that – looking in the rearview mirror.

The Fed resurrected a monetary tool from the 1960s dubbed Operation Twist, after the dance craze the Twist (Fed paper). Early Boomers will remember Chubby Checker. The Fed began selling the short-term Treasuries they owned and buying long term Treasuries. By increasing the demand for long term Treasuries, the Fed drove down long-term interest rates as an inducement for businesses and consumers to borrow. Despite the low rates, consumers continued to shed debt for another year. How effective was Operation Twist – maybe a little bit (Survey).

As the price of oil declined in late 2014 and the Fed ended yet another round of QE (QE3), there was a real danger of moving into a recession. Notice the decline in GDP growth (red) and money velocity (blue).

The downward trend barely reversed itself in the 3rd quarter of 2016, just before the election, but not by much.

The election of Donald J. Trump and a single party controlling both houses of Congress kindled hope of a looser regulatory environment and tax reform. Only then did the speed of money turn consistently upward. But we are not out of the woods yet. A year later, in late 2017, money velocity is still negative. As I said earlier, buyers and sellers still cannot agree on price. There is a mismatch in confidence and expectations. Until that blue line turns positive, GDP growth will remain tepid or turn negative.

///////////////////

M*V = P*Q is an identity that equates money supply (M) and demand (V) to inflation (P) and output (Q).