May 22, 2022

by Stephen Stofka

Consumer spending during the pandemic and in the post-pandemic recovery has been strong. Inflation adjusted retail sales have averaged 5.6% annual growth since December 2019 (FRED, 2022a). However, the disruptions caused by the once-in-a-century pandemic have made the annual growth rates erratic, particularly those in the spring months when the pandemic hit. In spring 2021, retail sales numbers showed an annual increase of 48% over the previous year. Older Americans had been getting vaccines in the first months of 2021, shops were reopening and people were spending money. The economy was recovering but the size of the recovery was a “base effect.” Retail figures in 2021 were compared to retail sales in March and April 2020 when the economy was largely shut down. The American economy is so large that it is not capable of producing 50% annual growth in real sales.

Because the spring 2021 numbers were so strong, the numbers this spring look shaky. When the April retail numbers were released this week, traders began to mention the word recession and the market sank several percent. When people swarmed into stores in the spring of 2021, Target (Symbol: TGT) reported an increase of 22% in same store sales. A realistic portrayal of a customer behavior trend? No, it was an artifact of the pandemic disruption. In the first quarter of this year, the company reported a slight decline compared to those year-ago numbers. The reaction? The company’s stock fell 25%, an overreaction in a thinly traded market, and its worse loss since October 1987 when the broader stock market fell more than 20% in one day.

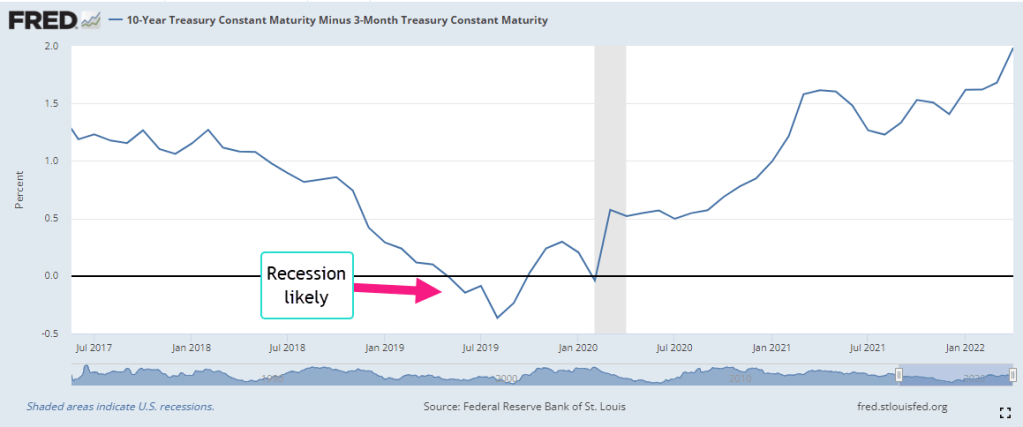

The stock market gets all the headlines each day but it is small in size relative to the bond market where the world’s lifeblood of debt and credit is traded. Over time the differences in interest rates between various debt products indicate trends in investor sentiment. These differences are called spreads. A common spread is a “term spread” between a long-term Treasury bond – say ten years – and a short-term Treasury of three months (FRED, 2022b). Short-term interest rates are usually lower than long-term rates because there is less that can go wrong in the short-term. When that relationship is turned upside down, it indicates a recession is likely in the near-term like a year or so. Why? Financial institutions are now expecting the opposite – that there is more that can go wrong in the short term than in the long term. They will be less likely to extend credit for new investments, business or residential.

For the past forty years, this spread has been a reliable predictor of recessions and it does not confirm the market’s recent concern about a recession. There are a few shortcomings with this indicator. With a wide range of several percent over five years, it has a lot of data “noise” that might obscure an understanding of the stresses building in the bond market and economy. Secondly, Treasury bonds are a small part of the bond market and carry no risk of default. We would like a risk spread between the rates on corporate bonds and those on Treasury bonds. Thirdly, the Federal Reserve has much less influence over corporate bond rates than it does on Treasury bond rates. Comparing corporates and Treasuries would give us a better sense of the broader market sentiment.

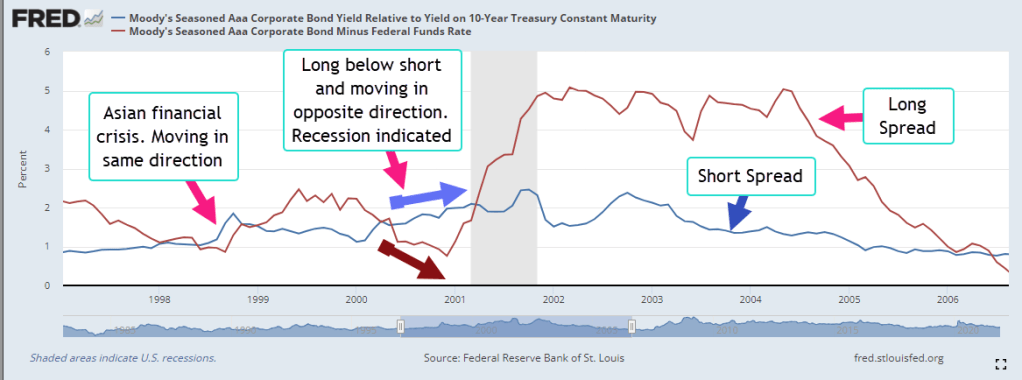

Moody’s Investors Service, a large financial rating company, computes the yield, or annualized interest rate, of an index of highly rated corporate bonds in good standing with a term longer than one year. The yield spread between corporate and long-term Treasury bonds usually lie in a range or channel of 1-1.5%. Like the lane markings on a highway, channels help us navigate data. The upper bound of 1.5% indicates a stress point. Let’s call that the long spread (FRED 2022c).

The Fed Funds rate is an average of rates that banks charge each other for overnight loans and the Federal Reserve tightly manages the range of this rate. For most of the past decade it has been below 1% and has often been close to zero. Let’s call the difference between the yield on corporate debt and the overnight rate the short spread (FRED, 2022d). Most of the time, the short spread is larger than the long spread. Just as with our first indicator of term spread, this relationship flips in the near term preceding a recession. Importantly, they continue to move in opposite directions for a while. The short spread keeps getting smaller while the long spread goes higher. In the graph below is the short recession after the dot-com bust.

In the right side of the graph the pattern will telegraph the coming recession in 2008. The graph below highlights the years after the financial crisis. The short term spread remained elevated above 1.5%, an indication of the persistent stress in the bond market. During Obama’s two terms in office, the short spread fell only once into the “everything is OK” range. Helped by the prospect of tax cuts in 2017, the spread declined to a lasting lull.

In the last half of 2019, the conjunction of these two time-risk spreads indicated a coming recession. The term spread we saw in the first graph also indicated a recession. They suggest that a 2020 recession was likely even if there was no pandemic. The Fed had been raising rates through mid-2019 to curb inflationary trends, then eased back a bit in the final months of that year. Were they seeing signs of economic stress as well?

How would the 2020 Presidential campaign have evolved if there had been no pandemic but a short recession lasting six to nine months? The Republican tax cuts enacted at the end of 2017 would have been shown to be a bust, doing little more than transferring wealth to the already wealthy. Mr. Trump would have certainly blamed the recession on Jerome Powell, the Chairman of the Fed, whom he had appointed. Powell would have been characterized as a Democratic stooge, part of an underground political plot to get Donald Trump out of the White House. The stories of what could have happened are entertainment for a summer’s campfire.

//////////////

Photo by Nadine Shaabana on Unsplash

FRED. 2022a. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Advance Real Retail and Food Services Sales [RRSFS], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/RRSFS, May 18, 2022.

FRED. 2022b. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Minus 3-Month Treasury Constant Maturity [T10Y3M], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/T10Y3M, May 19, 2022.

FRED. 2022c. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Moody’s Seasoned Aaa Corporate Bond Yield Relative to Yield on 10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity [AAA10Y], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/AAA10Y, May 19, 2022. The “long” spread.

FRED. 2022d. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Moody’s Seasoned Aaa Corporate Bond Minus Federal Funds Rate [AAAFF], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/AAAFF, May 19, 2022. The “short” spread.