March 17, 2024

by Stephen Stofka

This week’s letter is about the effect of tax revenues on government, on the economy and the role that taxes play in our lives. Tax revenues are the income of a government at all levels – federal, municipal and state. Those revenues fund the courts and prisons, the police, the roads and cultural institutions that connect people together, yet no one wants to pay them. The essence of a tax is a private payment for a public benefit. Few object to the opposite, a public payment for a private benefit when they are on the receiving end of such a subsidy.

Regardless of the amount that people pay in taxes, they feel that they have a right to complain about any good or service that a government provides. It’s in the Constitution. First Amendment – freedom of speech. For those who work in a democratic government, the unpopularity of taxes presents an existential conflict. Paul Samuelson (1947) pointed out the difficulty of designing a purely lump-sum tax or subsidy. A lump-sum tax is like a head tax, a fixed amount of tax regardless of a person’s circumstances. Under such a system, the wealthiest and poorest person pay the same amount of tax. This violates a sense of proportionality that is a guiding ethical principle.

A fixed single rate of tax answers concerns of proportionality. As an example, many districts enact a set rate for residential real estate. However, states have been reluctant to adopt a single or flat rate of income tax. In 1987, Colorado was the first state to adopt a single tax rate, according to the Tax Foundation. Other states were slow to follow Colorado’s lead and less than a quarter of the states have adopted a flat tax rate. Revenue and proportionality are not the only concerns. By its nature, a democratic government is not fair. People elect representatives who will maximize their benefits and minimize their taxes. Politicians naturally want to lighten the tax load of regular voters. In a flat tax system like the one in Colorado, politicians have amended the definition of taxable income to benefit some taxpayer groups at the expense of other groups. Pension income like Social Security and state retirement plans is not subject to state income tax.

The federal government and the majority of the states enact a graduated income tax that penalizes effort at the margin. An employee who works an occasional day of overtime may be surprised by the additional taxes taken out of that additional pay. Payroll software treats that extra amount as though the employee worked overtime every week, increasing the annual income used to calculate the tax rate on that additional income.

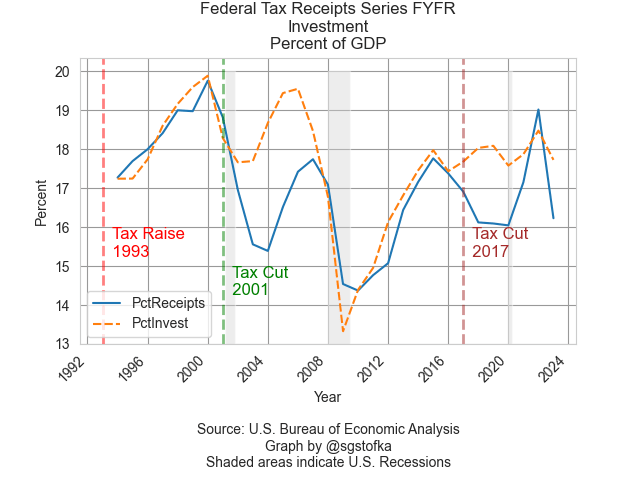

Republican politicians routinely champion their principle of low taxes. The justification for the tax cuts in the 1980s was based on an idea put forth in 1974 by the economist Arthur Laffer who drew an inverted curve on a napkin to illustrate the idea that higher tax rates might lead to lower tax revenues. Despite repeated evidence that lower tax rates lead to lower tax revenues, Republicans have clung to the idea. In the graph below, I have charted federal tax revenues as a percent of GDP. They do not include Social Security taxes.

According to the theory behind the Laffer Curve, lower taxes should spur more investment, more output, higher incomes and higher tax revenues. As we see in the graph above, tax raises led to higher revenues soon after they were enacted. Tax cuts did not. Believers in the theory claim that the cuts can take several years to work but this makes it hard to identify causality. In the graph below, I have added in investment as a percent of GDP.

The Bush tax cuts in 2001 certainly helped arrest the decline in investment following the “dot-com bust.” However, too much of that investment went into residential housing and led to the housing boom that preceded the financial crisis. Those tax cuts expired in 2010 and both investment and tax revenues improved. That raises the question: did higher taxes in 1993 and 2010 produce more investment? On principle, it seems unlikely. Following the 2017 tax cuts known by their acronym TCJA, investment again reversed a decline but had little effect on tax revenues. The rise in revenues as a percent of GDP was due to the fall in output as a result of the pandemic.

According to the neoclassical economist’s narrative, savings provide the source of investment. Taxes reduce savings and therefore reduce investment. Italian economist Pietro Sraffa (1932) reiterated a point made by Sir Dennis Robertson that savings were an inducement to more investment as well as a source of investment. Investment occurs in the period before consumption. People have money to save for two reasons. The first is that their incomes increase from new investment in production. Secondly, there are not enough goods in the marketplace to induce them to spend that extra income. The mismatch in supply and demand gives companies pricing power. Investors rush in to take advantage of the additional demand and the flow of new savings gives banks the confidence to make more loans.

For the past thirty years, federal revenues excluding social security taxes have averaged 17% of GDP. For that same period, the government spent 18.6% of GDP. The deficits have been persistent because the federal government consistently spends more than it taxes, an analysis confirmed by the Congressional Budget Office in a recent report. Republican lawmakers try to choke tax revenues to “Starve the Beast” – the beast being the size and reach of the federal government. To Democratic policymakers, our society needs constant remodeling, so they always have a plan for extra tax revenue. Neither party seems willing to resolve this political push-me-pull-you and the public has become used to deficits. There is always one more war to fight, one more wrong to right.

/////////////////

Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash

Keywords: tax cuts, investment, taxes

Samuelson, Paul Anthony. (1947). Foundations of Economic Analysis. Harvard University Press.

Sraffa, P. (1932). Dr. Hayek on money and Capital. The Economic Journal, 42(165), 42. https://doi.org/10.2307/2223735