March 12, 2023

by Stephen Stofka

Paradoxes in Savings

The week’s letter is about the relationship between savings and inflation. On Tuesday, Jay Powell, the Chairman of the Fed, announced that they would continue raising rates to get inflation under control. The market dived a few percentage points. There are no shortage of explanations for persistent inflation. Despite an inflation rate above 5% for the past year, the employment market remains strong, a puzzle to economists. I will take a look at how changes in savings affect inflation.

There are times when we coordinate our behavior for apparent reasons. The weather and seasons synchronize the activities of farmers. The harvest comes at a particular time and farmers need to rent more harvesting equipment, storage capacity, rail cars and trucks for transporting their crops. Suppliers are on a different time schedule than their customers. Supplying anything takes planning, investment and time.

Suppliers rely on the fact that buyers coordinate their buying decisions according to the seasons. Clothes, gardening and Christmas gifts are easy examples. Forty percent of homes are sold during the spring months. Except for big purchases, a buying decision takes less planning and this can create anomalies that suppliers are not prepared for. Sometimes it is a popular toy at Christmas or a clothes style made popular by a celebrity.

What causes asset buyers to coordinate their behavior? The economist John Maynard Keynes was particularly interested in that question. He attributed the phenomenon to “animal spirits,” an infectious rush of pessimism or optimism that affects the prices of assets first, then spreads to the purchases of goods. Normally, some of us are saving more than usual for something, while some of us are spending that savings, or borrowing to buy things. There is a balance of savers and borrowers. However, sometimes a general prudence causes everyone to save more than average and what emerges is a paradox, the Paradox of Saving. If everyone saves, then economic activity declines, unemployment rises, people spend down their savings and the economy finds a new equilibrium at a much lower growth rate.

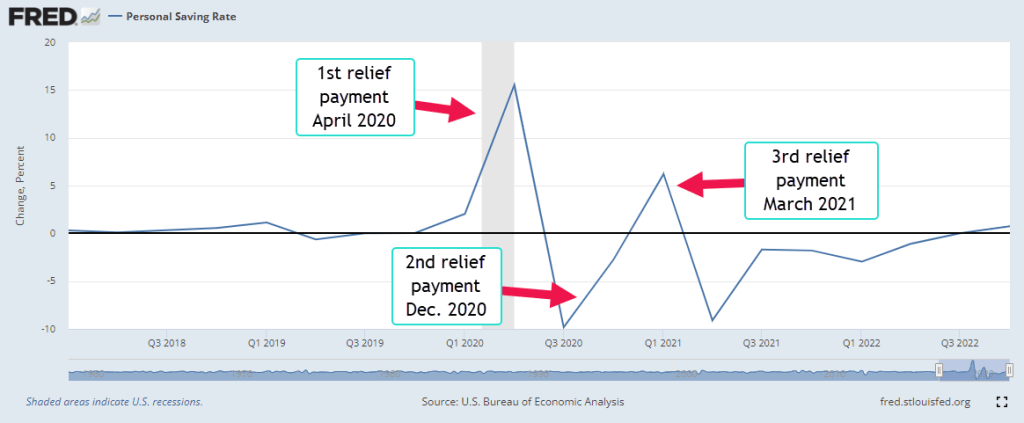

In the spring of 2020, a surge of Covid deaths in Italy and New York City prompted the closing of many businesses. City morgues were overwhelmed, forcing hospitals to rent refrigerated trucks to store the bodies. The NY health department supervised several mass burials. Residents in rural areas who were unable to catch their breath were flown to distant hospitals with the equipment and personnel capable of bringing the patients some relief. Because many workers had abruptly lost their income, the government issued relief payments to households throughout the country. With many entertainment venues closed, many of us increased our rate of savings. Below is a graph of the quarterly change in the personal savings rate.

The savings rate shot up 15%, a historic rise. Even during the high inflation of the 1970s, the savings rate rose by only 2.5% in 1975. Such an abrupt change in savings did have an effect on prices. When the change in the savings rate is negative, people are buying stuff with their savings. Companies could take advantage of supply chain bottlenecks and raise prices. This helped make back what they had lost in profits in 2020. The quarterly change in prices began to rise, as the red line in the chart below indicates. Note that inflation is the annual, not quarterly, change in prices.

Look on the right side of that chart and you will see the blue savings line turning positive. A steadily higher savings rate should exert some calming effect on prices. I then ran a statistical regression on the annual change in both prices, i.e. inflation, and the savings rate for the past 35 years. The effect of a 1% rise in the savings rate is about a 1% decrease in the inflation rate and explains 21% of the movement in inflation.

What can you do with this information? Quick erratic changes in savings have an effect on prices. Immediately after 9-11 there was an abrupt rise and fall in savings but the change was much less than the pandemic shock, which was truly historic. In 2008 came another shock, an abrupt shift in savings and an accompanying rise in prices in the summer of 2008 before the Lehman meltdown in September and the economy tanked in the 4th quarter of 2008. These changes in savings rates don’t occur very often, but when they do we should pay attention.

////////////////////

Photo by Johannes Plenio on Unsplash