April 12, 2015

Last week I wrote about the recent flow of investment dollars to markets outside the U.S. This week emerging markets (EEM, VWO, for example) shot up another 4%. For the first time since last October, the 30 day average in these two index ETFs just broke above the 100 day average.

******************************

Job Openings (JOLTS)

February’s JOLTS report from the BLS, released this past Tuesday, showed that the number of job openings is nearing the heights of the dot com bubble in 2000.

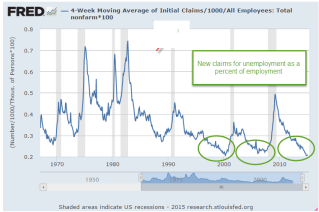

Last week we saw that new claims for unemployment as a percent of people working were at historically low levels. I’ll show the graph again so I can lay the groundwork for an explanation of why bad things can happen when things get too good.

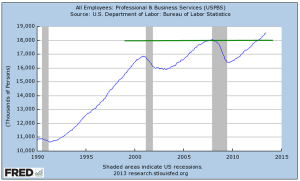

Here are job openings as a percent of those working. I’ll call it JOE. In 2007, JOE approached 3.5%. In 2000 and these past few months, it exceeded that. As openings fall below a previous low point, recessions follow as the economy “corrects course.” I have noted these transition points on the chart below. September’s low of 3.3% marks the current low barrier. Any decline below that level would be cause for worry.

Let’s look at it from another angle. Below are job openings as a percent of the unemployed who are actively looking for a job. This metric would give us a rough idea of the skills and pay mismatch. This looks a bit more tempered. We are not at the high level of 2007 and not even close to the nosebleed level of 2000.

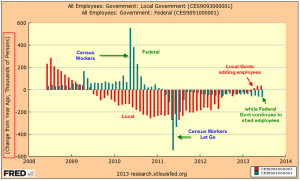

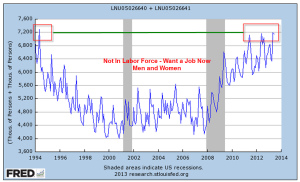

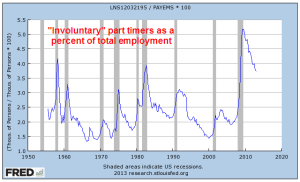

As openings grow, one would expect that some who have been out of the labor force would come back in but that doesn’t seem to be the case this time. The participation rate remains low. The reasons for this trend are partly demographic – aging boomers, small GenX population, end of the female labor “wave” into the labor force during the past few decades – but we should expect to see some uptick in the participation rate, some positive upward response to economic growth.

As jobs become harder to fill or applicants want more money to fill those jobs, employers may decide to cut back expansion plans rather than hire people who are are either too costly to train or who might not meet the company’s work standards. Employees who previously tolerated certain conditions or a level of pay at their job now act on their dissatisfaction. They may leave the job or ask for more money or a change in conditions. Little by little investment spending ebbs, then declines a bit more, reaches a threshold which triggers layoffs, and another business cycle falls from its peak.

**********************

Bank of Japan

Recently the NY Post reported that the Bank of Japan (BOJ) was buying equities and the author implied that BOJ was pumping up the stock market. The central bank in the U.S. buys only government bonds, not equities. Warnings of doomsday are popular in financial reporting because people pay attention. The truth just doesn’t get much attention because it is not exciting. I want to help the reader understand how misleading these kind of cross country comparisons can be.

Here is a comparison of the holdings of the U.S., Japanese and European central banks. Look closely at the holdings of insurance and pension funds in the U.S. and Japan. Notice that U.S. pension funds (which are government funds or private funds guaranteed and regulated by the U.S. government) have 9% equity holdings while Japan’s insurance and pension funds have only 2%. Combining the holdings of the central bank and insurance and pension funds, we find that Japan has 4% in stock assets while the U.S. has 9% of its assets in stocks. Contrary to this reporter’s implications, it is the U.S. government that is pumping up the stock market far more than the Bank of Japan.

The author quotes a Wall St. Journal article from March 11, 2015: “The Bank of Japan’s aggressive purchasing of stock funds” but only seven months ago, on August 12, 2014, that same newspaper reported: “As Tokyo shares fall back from their recent highs, the Bank of Japan has been significantly stepping up its purchases of domestic exchange traded funds.” [my emphasis]

Note the difference in wording. The earlier article notes that BOJ is buying domestic equities, particularly ETFs, which are baskets of stocks. The later article leaves out these important distinctions, leading a reader to believe that BOJ policy might be pumping up the U.S. equity market or any market, for that matter. The data does not support that contention.

What U.S. investors should be concerned about (I mentioned this in last week’s blog) is that federally guaranteed pension plans and government pension plans are finding it difficult in this low interest rate environment to meet their projected benchmark returns of 7% to 8%. A more realistic goal is 5% to 6% for a large fund with a balanced risk profile. Pension plans are having to take on more risk at a time when boomers are retiring and wanting the money promised in those pension plans. These investment pools can not afford to wait five years for asset values to recover from a severe downturn, making them more likely to adjust their equity or bond positions as quickly as they can in the case of a crisis of confidence in these markets. Be aware of the underlying environment we are living in.