April 28th, 2013

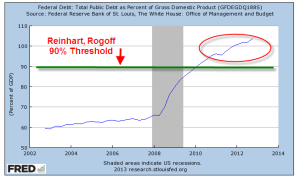

A fight between economists is not as exciting as a dinosaur smackdown (Jurassic Park), but the controversy can be as damaging. Politicians and pundits love to trot out those economic studies and theories which justify their actions or political point of view. In 2009, two economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff (now affectionately known as RR), published a study which showed that a country’s GDP growth becomes slightly negative when its debt grows above 90% of its GDP. The study was cited by many politicians and pundits in Europe and the US, including VP candidate Paul Ryan, as they proposed various forms of austerity to curb the explosive growth of national debt.

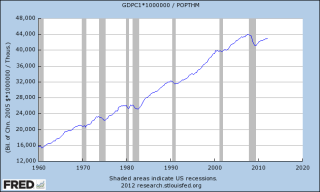

Here’s what the debt to GDP ratio looked like 1940 – 1960

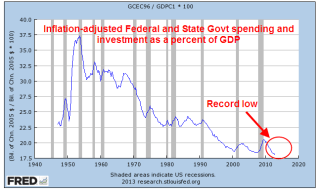

In the years 1947 – 1959, we had an annualized growth rate of 3.6% but a strong component of this growth was our strategic advantage in exports, being the manufacturing capital of the world after much of the production capacity of the developed world was destroyed in WW2.

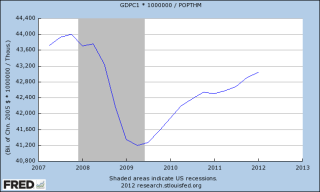

Here’s what it looks like now; the same spike of debt.

But we have lost the advantage of being the leading manufacturer.

Given the assignment of replicating an existing economic study, Thomas Herndon, a PhD candidate at UMass, discovered some glaring spreadsheet errors in the original data set compiled by RR. You can read an Alternet article summarizing the details here.

Some quick background. There are two categories of economic policies. Fiscal policy encompasses taxing and spending measures by a government. Monetary policy is conducted by a country’s central bank and are targeted at the supply of money and interest rates. Economists argue over which policy is more effective in a given circumstance. Each of us goes about our daily lives under the influence of both fiscal and monetary policy.

During the 1930s depression, the economist John Maynard Keynes proposed that governments borrow and spend money during recessions to make up for the lack of aggregate demand in the economy. After the economy recovered, governments would then raise taxes to pay back the borrowed money. Another leading economist, James Buchanan, predicted that nations who followed Keynes’ ideas would have permanent deficits. While Keynes’ economic model was elegant, Buchanan argued that there was no incentive for a politician to raise taxes.

In 1963, with the publication of A Monetary History of the U.S., economists Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz argued that the Depression had been largely a result of failed monetary policy by central banks. During the 1970s, when government fiscal policies of increasing intervention in the economy failed to ingnite growth or curb inflation, Keynes’ policies fell into disfavor.

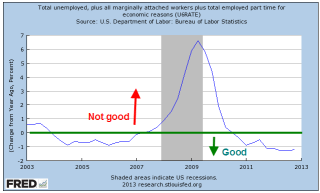

The age old debate about the effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policy never dies. The recession that began in 2008 revived Keynes’ ideas. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, economist Paul Krugman and Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke were proponents of monetary solutions for Japan’s moribund economy. As the world economy imploded in 2008, both men changed course and became advocates for fiscal policy as the most effective solution for the country’s economic woes.

In a recently published paper UMass professors Michael Ash and Robert Pollin (Herndon’s advisors), explained their methodology and took RR to task for their lack of follow up on incomplete data analysis after several years. What they had missed was a follow up paper by RR in February 2011 and another published in the summer of 2012. In these papers, RR modified their initial findings, saying that GDP growth slowed but did not necessarily turn negative.

In a WSJ blog post , RR answered the critique from the UMass Professors. They admitted their spreadsheet error but reaffirmed their other assumptions in the study and their amended conclusions.

Paul Krugman weighed in (or waded in?), voicing his disappointment with RR’s methodology and their conclusion. Krugman does make a point oft repeated in the social studies: correlation is not causation. Does high debt cause slow GDP growth? Or, does slow GDP growth cause high debt? Or can we say that there is some indication that they accompany each other?

At Econbrowser, U. Cal professor James Hamilton, reviewed RR’s methodology and Ash and Pollin’s critique. (Link) To which, Professors Ash and Pollin responded with some good points.

Ash and Pollin have made the original data available. Some have accused RR of purposefully leaving five countries out of their data, saying that these five countries would have weakened or invalidated their findings. The Excel file shows that this was a simple – but dumb – mistake, not some nefarious plan by RR. The countries left out are on the last five worksheets which are arranged in alphabetical order. What surprises many is that two prominent economists could publish a paper based on work that had so little verification before publication.

What I question is RR’s decision to include many of the smaller countries at all in their analysis. Finland and Ireland each have less than 2% of the GDP of the U.S.

What I do hope is that this controversy will spur more analysis of the relationship between a nation’s debt load and its economic growth. What I am afraid of is that this will discourage researchers from sharing their working data. Reinhart and Rogoff are to be highly commended for doing so.