September 4, 2022

by Stephen Stofka

On this Labor Day Weekend I’ll review some current employment numbers and look at a historic trend whose results surprised me. The August employment report released this past Friday buoyed the stock market. Job gains remained strong but moderated from the half million jobs gained in July. The slowing gains indicated a predicted response to rising interest rates. Had the number of job gains risen to 600,000 for example, the market might have sold off. Why? Currently the market is predicting a rise in rates to a range of 3.5 – 4.0% in the next year. A labor market resistant to rising rates would have implied that the Fed would have to set rates even higher to cool inflation. Secondly, the unemployment rate rose .2% to 3.7%, another indication that rising rates are having a modest effect on employment. Modest is the key word.

The participation rate – the percentage of working age people who are working or looking for work – rose slightly to 62.4%, still 1% below pre-pandemic levels. Reopening classrooms and the further relaxing of pandemic restrictions are contributing factors. Additional family members may be joining the workforce to cope with rising household expenses. The number of marginally attached workers – those who want a job but haven’t actively looked for a job in the past month – declined to 5.5 million, still a half million above pre-pandemic levels. These “discouraged” workers remain below 1% of the labor force, a level indicating a strong labor market. President Obama inherited an economy in crisis and the percent of discouraged workers declined to nearly 1% but not below. As the rate fell below 1% in the first months of the Trump presidency, Mr. Trump cheerfully took credit. A politician and his followers blow their horns to encourage others others to join their coalition.

Surprises

A 17,000 employment gain in financial jobs surprised me. Rising interest rates have lowered mortgage applications and I thought the employment numbers for the financial industry would decline. Lastly, weekly earnings are up over 5.6% but have not kept up with inflation. Unemployment numbers are low, job openings are high. Why don’t workers have more pricing power?

A Historic View

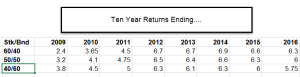

Earlier this week I was looking at labor slumps since World War 2. These slumps are periods at least six months long. They start when the number of workers first declines. They end when employment finally surpasses its previous high. Employment first declines about two months after the start of a recession, as the NBER later determines it*, so it is a lagging indicator.

I split the period 1950-2022 into two 36 year periods. The first period lasted from 1950-1986; the second period from 1986-2022. In the first period there were 7 recessions and employment slumps. In the second period there were 4 recessions and slumps. Even though there were more recessions in the first period, the number of months of sagging employment was far less than the second period, 131 vs 168. No doubt that was due to the 75 month long slump of the Great Recession. That’s an extra three years of a lackluster job market which affected demand for workers and the pay they could command. In the chart below I have sketched the labor slumps. Economic recessions have a lasting impact on the labor market.

In the first period, the longest slump lasted 26 months during the early 1980s recession when the unemployment rate rose above 10% and inflation was in the teens. That began in September 1981 and lasted until November 1983. In the second period, the job market sagged during the Great Recession for 75 months, from February 2008 until May 2014. The least severe slump was this last one, beginning in April 2020 and ending in April 2022. The recession in 2001 lasted only 6 months but the labor slump lasted 40 months, from June 2001 until October 2004, just before the 2004 election.

Wages

More prolonged slumps affect wages. In the chart below the BLS compares nominal and inflation-adjusted median weekly earnings over the past twenty years. The real earnings of workers have barely risen because they are not sharing in the productivity gains of the past decades. The earnings gap between men and women has varied little during that time.

Contributing Factors

Why are labor slumps lasting longer during this later period? There are many contributing factors. When there was a larger manufacturing base recessions were more frequent but workers were brought back to work more quickly. The two recessions of the 2000s made that decade the hardest on workers. The two labor slumps totaled more than five years during the decade.

The 1970s gets a bad rap but it was the 1950s which had the second largest number of months when employment sagged – a total of 3.5 years. Standing five decades apart, the 2000s and 1950s had very different economic and family structures. Fewer women worked in that post war decade. The waiting period for unemployment insurance was twice as long and benefits lasted less than four months. These were inducements for workers to find any kind of work to support their families. Union membership was much higher in the 1950s so workers could rely on those benefits while unemployed. They would not have wanted to lose their union membership so they might have worked off the books for cash while they waited for hiring to pick up at the same company or the same industry. Like so many economic trends, the interaction between factors is complex and not readily identifiable.

Conclusion

Reckless speculation was the main contributor to the two recessions in the 2000s. Financial shenanigans played a smaller role in the slump of the early 1990s. The increased length of these slumps in the last four decades supports an argument that our economy has lost too much of its manufacturing base and is out of balance. There is too much financial speculation and not enough actual production. The federal deficit has increased so much in the past two decades because the private economy cannot generate enough growth on its own.

//////////////

Photo by Patrick Schneider on Unsplash

*The NBER marks only the decline portion of a general economic slump so the gray shaded areas will be shorter than the labor slump. However, the chart illustrates the prolonged effect that an economic decline has on the labor market.

BLS. (2022). Median usual weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by sex. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved September 2, 2022, from https://www.bls.gov/charts/usual-weekly-earnings/usual-weekly-earnings-over-time-total-men-women.htm

Price, D. N. (1985, October). Unemployment insurance, then and now, 1935–85. Social Security Administration. Retrieved September 3, 2022, from https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v48n10/v48n10p22.pdf