April 28, 2024

by Stephen Stofka

The subjects of this week’s letter are home prices, household income and property taxes. The policy of using property tax revenue to fund public education has provoked controversy since the 19th century. Like other social species we are watchful of threats like freeloading to our group’s cohesion, however we determine “our” group. Newcomers to an area are often regarded with suspicion as being freeloaders who get from the group before they have contributed to the common welfare. This suspicion often underlies the heated debates that erupt at local council meetings. I will begin with property valuations, the basis of property taxation.

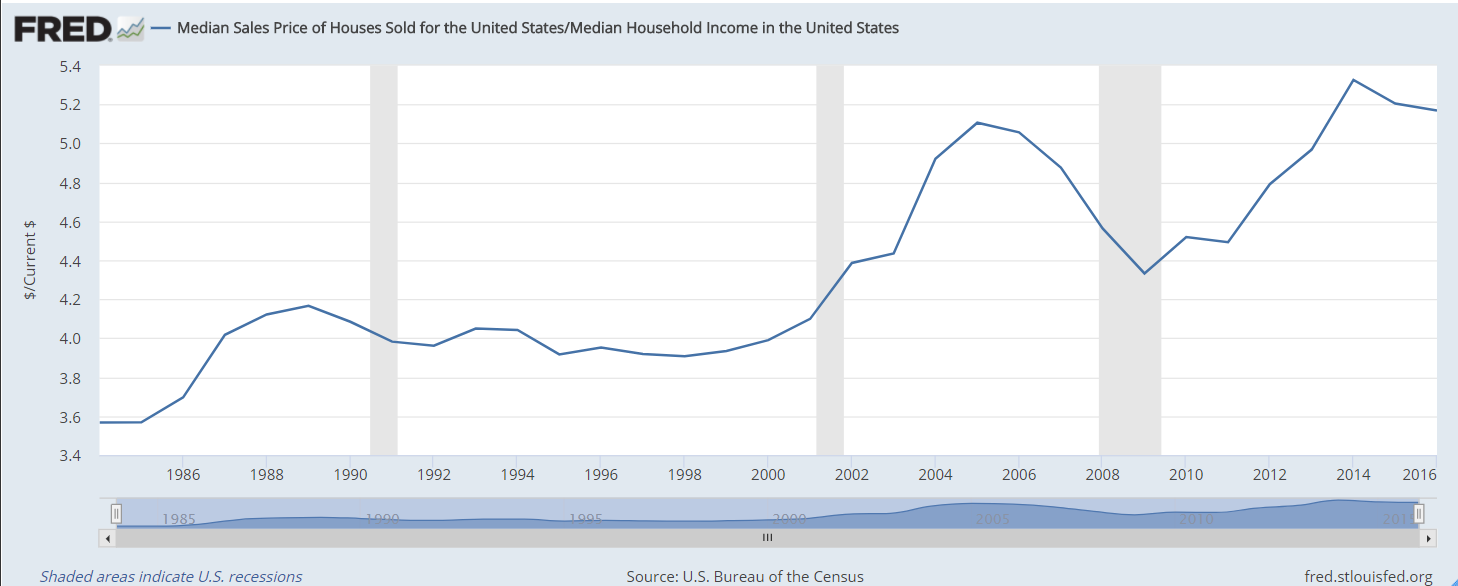

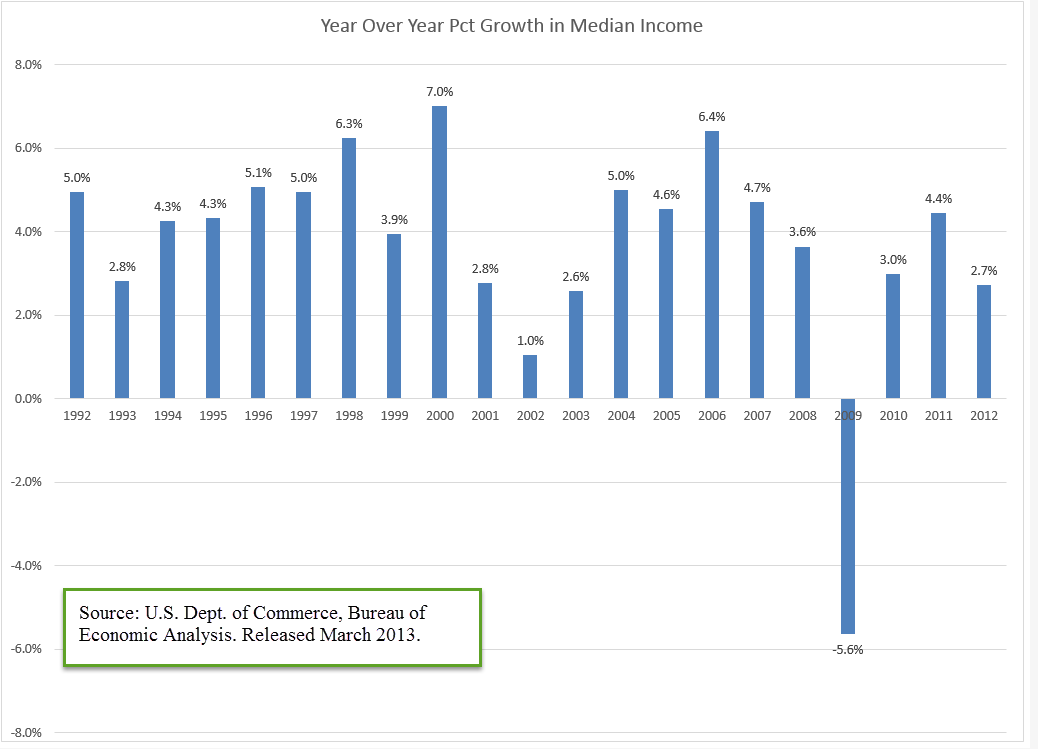

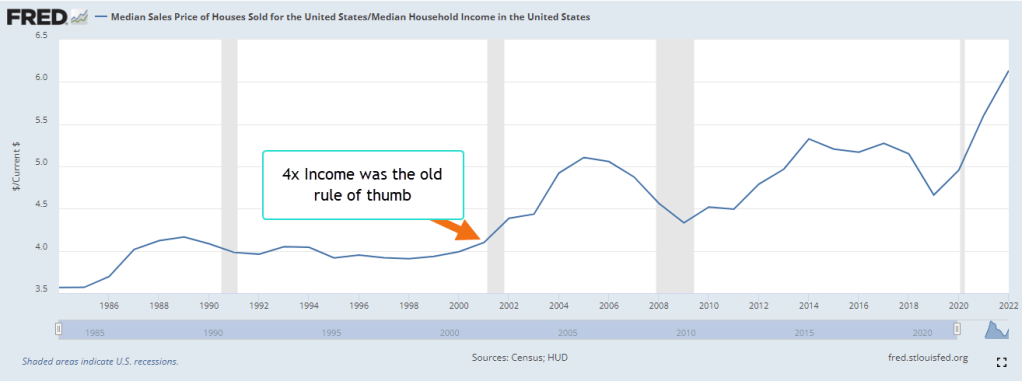

As a young man I was taught not to buy a home that was priced more than four times my income. In 2022, families paid more than six times the median household income, as shown in the chart below. Despite the high prices, mortgage debt service is a tame 10% of the household disposable personal income. Almost 40% of homeowners have a fully paid mortgage, according to Axios. Many homeowners hold mortgages at the historically low rates of the last decade. If higher mortgage rates persist for several years, we may see greater delinquency rates as recent buyers cope with payments that stretch their budget.

The Center for Microeconomic Data at the NY Federal Reserve has tracked household finances for more than twenty years. The highest percent of total household debt continues to be mortgage debt at 68% to 70%. Mortgage debt has grown at an annual rate of 3.9%, slightly more than the 3.7% annual increase in owner equivalent rent that I discussed last week. A low 3% of mortgages are more than 30 days delinquent, down from 11% to 12% during the 2008-2009 financial crisis. Only 40,000 people are in foreclosure, less than half the number in 2019. The numbers today are the lowest on record except for the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 when many foreclosures were halted.

As I discussed last week, property prices reflect the anticipated cash flows from the house during a 30-year mortgage, a process called capitalization. The home buyer replaces the seller in the stream of cash flows from the house. Because property taxes are based on the appraisal values, the taxing authority implicitly bases property taxes on cash flows that a homeowner has not received yet. Each state sets an assessment rate that is a percent of the appraised value of the home. Each taxing authority within the state then charges a dollar amount – the mill value – per thousand of that assessed value. A home with an appraised value of $500,000 and an assessment rate of 8% would have an assessed valuation of $40,000. If the mill levy were $100 per $1000 of assessed value, then the homeowner’s property tax bill would be $4000. The effective property tax rate would be $4000 divided by $500,000, or 0.8%. Investopedia has a longer explanation for interested readers.

Each state taxes property at different rates. Colorado charges ½% of the appraised property value, one of the lowest in the nation. California averages ¾%. Texas averages a whopping 1.74% of home property values but has no income tax. Families earning the median household income and owning a house valued at the median house price in Texas and Colorado pay the same combined property and income tax of $5883 and $5669, respectively. Colorado has a cheaper tax burden despite having an income tax and far higher median house values. The same family living in California would pay $8256, largely because their property tax bill would be about the same as in Texas because the home values are more than double those in Texas. I will leave data sources in the notes.

Many districts give seniors a discount on their property taxes, effectively throwing a higher burden on working homeowners. Some argue that these exemptions should be means tested, effectively lessening or eliminating the discount for seniors with higher incomes. A wave of seniors may move to an inter-urban area that features lower home prices yet is within an hour of vital medical services like a hospital. The higher demand drives up home prices for others who have lived in the area for decades. Secondly, seniors consume more medical services and public accommodations. That requires more public spending, which is shared by the entire community and leads to resentments and contentious public meetings at the local town hall.

The majority of property taxes are used to fund public schools, and it is the largest line item on an individual homeowner’s property tax statement. This system of funding raises principled objections from childless couples and those who privately school their children, but are expected to share the burden of funding public schools. Homeowners have often resented having to fund the schooling of recently arrived immigrants. In the 19th century a wave of immigrants from Catholic Ireland, then Catholic Italy prompted many states with Protestant majorities to pass laws that excluded public funding for schools run by Catholics. Since the 16th century, the two main branches of Christianity had fought bloody civil wars in Europe and Britain. Those who colonized America brought those antagonisms with them.

During the 1970s, the number of encounters at the southern border increased almost ten times, according to the CBP. High inflation and migration of Amerians to western states caused a surge in property valuations and higher property taxes. In 1978, a taxpayer revolt in California led to the passage of Proposition 13 limiting property tax increases. In some school districts, undocumented parents had to pay a fee to enroll their children in public school.

In a 1982 case Plyler v. Doe, a slim 5-4 majority on the Supreme Court ruled that undocumented immigrant children did not have to pay a fee to go to school. The court reasoned that the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment extended protection to “persons,” not “citizens.” Therefore, a state could not provide public benefits to one child in a school district and not another child because their parents were undocumented. The court interpreted “protection” to include public benefits, a construction that the Connecticut Constitution made explicit in 1818 with the phrase “exclusive public emoluments or privileges from the community.” The conservative majority on the Supreme Court overruled an interpretation of the due process clause in the 14th Amendment that justified the 1972 Roe v. Wade decision. This court might revisit this interpretation of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment as well.

Districts with lower property valuations struggle to raise adequate taxes to meet minimum educational standards. They may have to tax homeowners at a higher rate than a neighboring district, raising legal questions about uniformity and proportionality. The disparity in valuation was the subject of the 1997 Claremont decision by the New Hampshire Supreme Court. At the time, local districts provided 75% to 89% of funding for elementary and secondary education. The state’s general fund provided only 8% of school needs. The decision forced the state to distribute tax revenues among districts to meet adequate education standards for all children in the state. A 2017 analysis found that states now provide almost half of public education funding, relying on income tax revenue to smooth disparities in income among districts within each state.

People do not like paying taxes but grudgingly accept them. People elect local officials to decide on spending priorities yet some homeowners object to the way their taxes are spent. On my property tax bill are eleven items which include funding for schools, the city’s bonds, police, fire, libraries and flood control. Homeowners might prefer a questionnaire of thirty categories of spending which allowed them to allocate their tax dollars by percentage when they paid their property tax each year. In my district, a half-percent goes to affordable housing, three percent to social services. Some might prefer 5% or more. A homeowner paying online could elect to answer the questionnaire online. Would homeowners respond? Next week I will begin an exploration of various aspects of consumption, the chief component of our economy.

///////////////////////////

Photo by Museums Victoria on Unsplash

Keywords: housing, home prices, mortgage, property tax

Property taxes by zip code and state can be found at Smart Asset

Median home prices by state are at Bank Rate

Median Sales Price of Homes Sold in the U.S. is FRED Series MSPUS at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/ Median Household Income in the U.S. is series MEHOINUSA646N. The ratio of mortgage payments to disposable personal income can be found here. The home price to property tax ratio can be found here