August 23, 2020

by Steve Stofka

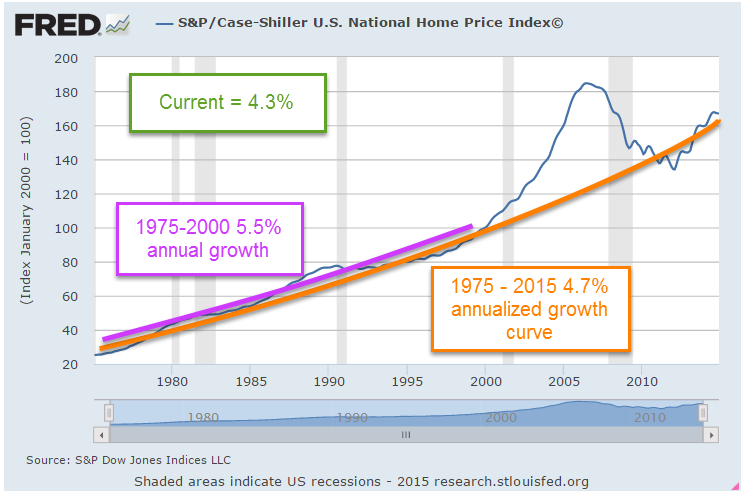

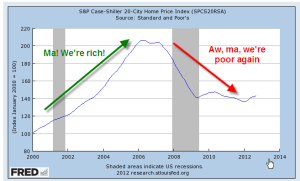

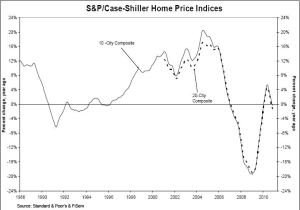

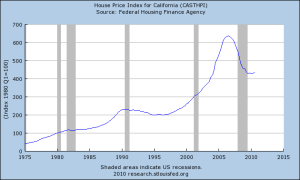

During this pandemic, the Federal Reserve has been supportive of the asset markets and the government’s stimulus and relief programs. It’s immediate response was to lower interest rates, a boon for home buyers. This week we learned that home sales had rebounded 25% in July and are up 7% over last year at this time. Low interest rates have benefited homebuyers but penalized savers and pension funds who must generate a current income flow from their savings base.

During the 1930s Depression, the economist John Maynard Keynes argued that, because people want to hoard during a downturn, a central bank should maintain an interest level sufficient to induce people to deposit their money in banks (Keynes, 1936). Government-insured savings accounts helped solve that confidence problem. Keynes’ language and sentence construction are laborious, leading some people to think that Keynes argued for a policy of ultra-low rates during economic declines. He did not. Low interest rates are not a Keynesian solution.

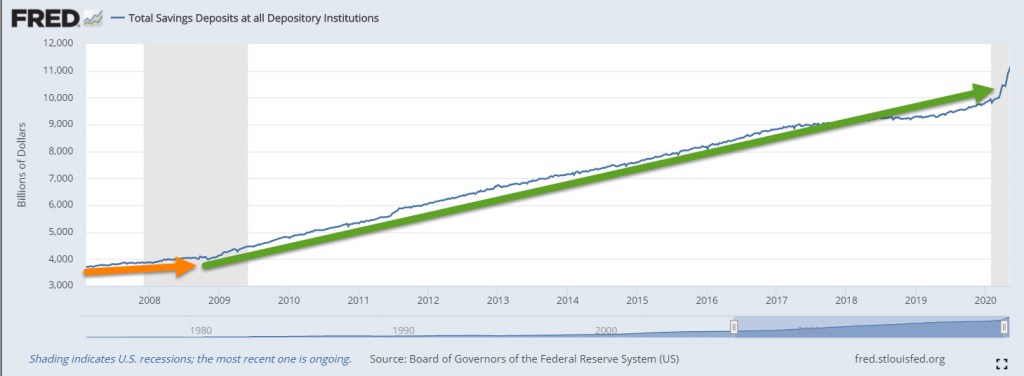

Despite the low rates, the amount of savings has doubled since the financial crisis in September 2008. There is a distinctive change in savings behavior at that important point.

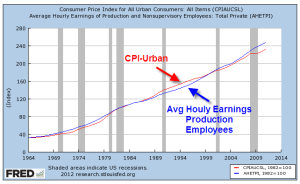

With a savings base of $11 trillion, every 1% decrease in interest rates is a transfer of income of $110 billion from savers to borrowers. Who is the largest borrower? The government. Aren’t low interest rates good for businesses? No, Keynes argued rather unartfully in Chapter 15. Borrowing is a long-term decision, and subject to error. When interest rates are particularly low, like 2%, there is no wiggle room for error in the expectations of businesses who might borrow. For homebuyers, expectations of future business conditions are a small factor.

During an economic decline, people and businesses are guided more by short-term decisions. When interest rates are low like today, banks don’t want to lend because they aren’t confident in the flow of deposits to maintain their liquidity. Banks need that flow of deposits to meet the outflow of money when they make loans (Coppola, 2017). Entrepreneurs are reluctant to borrow for expansion because they are not confident in the accuracy of their long-term expectations. They borrow to pay back more predictable future obligations, particularly current and future stock grants to their key employees. Borrowing money to fund stock grants does not create jobs but helps inflate stock prices.

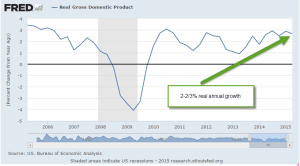

Keynes badly underestimated the political forces that guide a central bank’s decision making. As it did a decade ago, the Federal Reserve has lowered interest rates to near-zero, the opposite of Keynes’ prescription. Low interest rates do not benefit bank stocks, which have declined by 25% and more. A select group of technology stocks are booming as people consume more digital services at work and play. Borrowing by businesses jumped in response to the CARES act but many businesses kept those borrowed funds liquid to avoid insolvency during this crisis. We can expect slow growth as consumers and businesses continue to make short-term decisions, and asset markets are warped by central bank policy.

//////////////

Notes:

Photo by Christina Victoria Craft on Unsplash

Coppola, F. (2017, November 01). Bank Capital And Liquidity: Sorting Out The Muddle. Forbes Magazine. Retrieved August 15, 2020, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/francescoppola/2017/10/31/bank-capital-and-liquidity-sorting-out-the-muddle/

Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment interest and money (p. 124). New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace & World.