January 21, 2024

by Stephen Stofka

Thanks to an alert reader I corrected an error in the example given in the notes at the end.

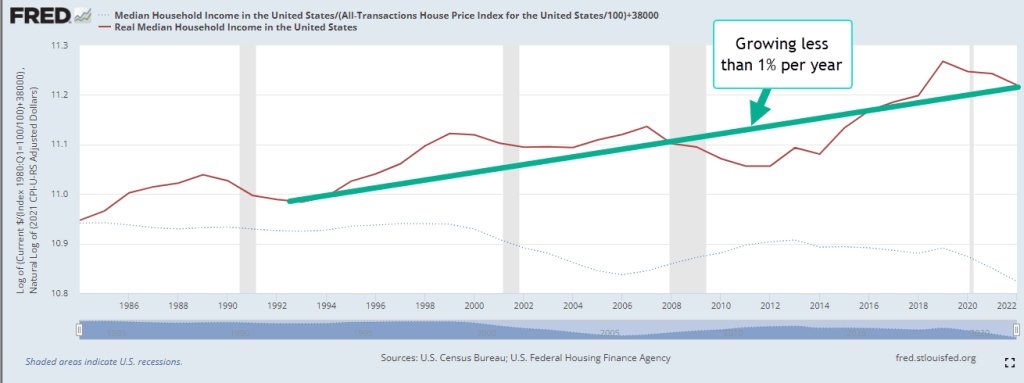

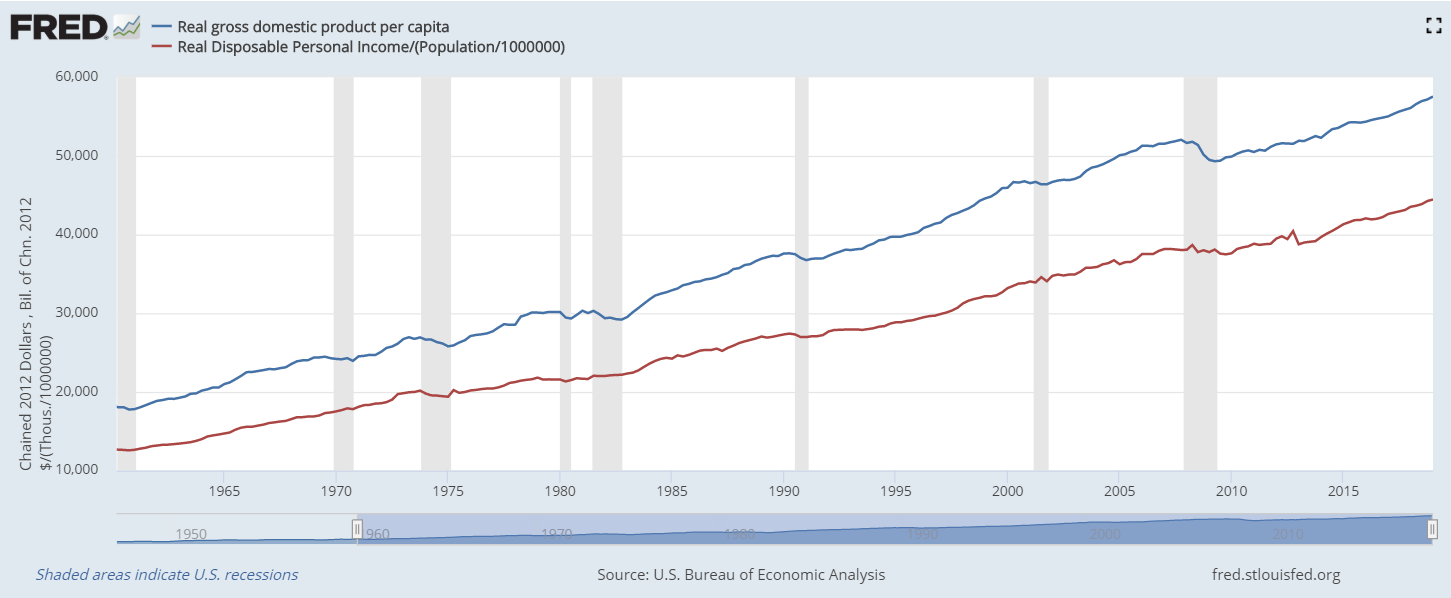

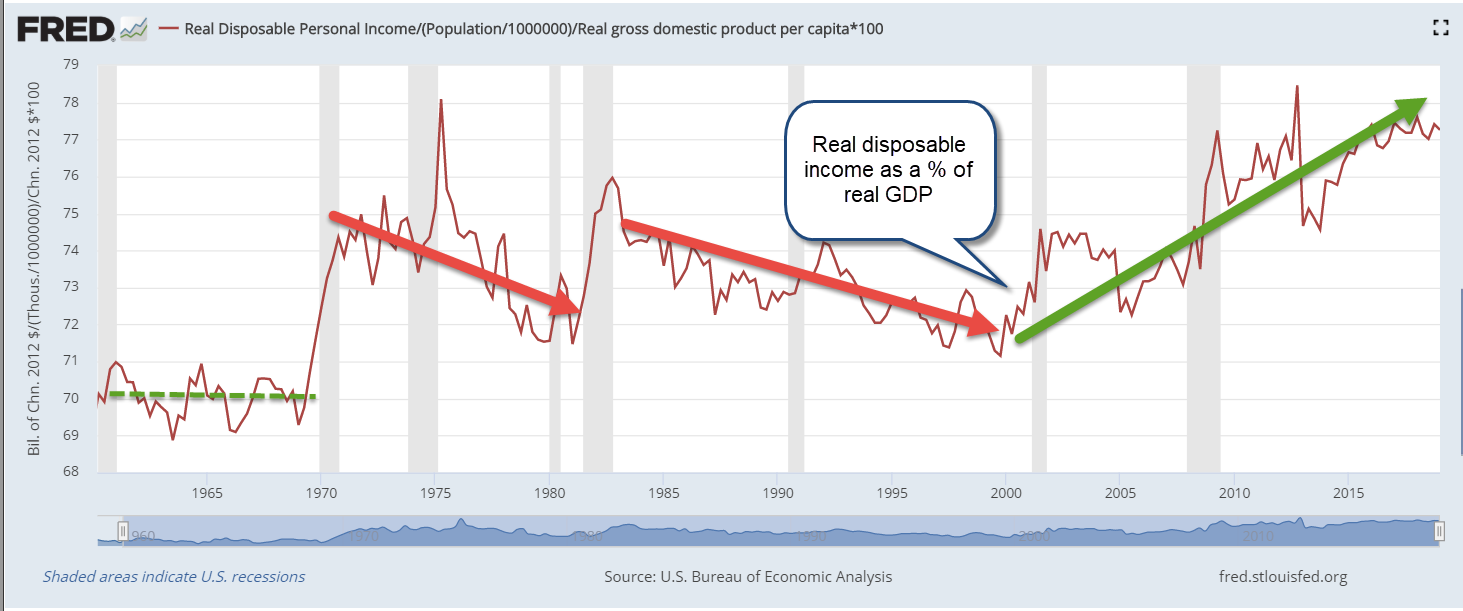

This week’s letter is about the cost of necessities, particularly shelter, in terms of personal income. Biden’s term has been one of historic job growth and low unemployment. Inflation-adjusted income per capita has risen a total of 6.1% since December 2019, far more than the four-year gain of 2.9% during the years of the financial crisis. Yet there is a persistent gloom on both mainstream and social media and Biden’s approval rating of 41% is the same as Trump’s average during his four-year term. Even though there are fewer economic facts to support this dour sentiment, a number of voters are focusing on the negatives rather than the positives.

I will look at three key ratios of spending to income – shelter, food and transportation – to see if they give any clues to an incumbent President’s re-election success (a link to these series and an example is in the notes). Despite an unpopular war in Iraq, George Bush won re-election in 2004 when those ratios were either falling, a good sign, or stable. Obama won re-election in 2012 when the shelter ratio was at a historic low. However, the food and transportation ratios were uncomfortably near historic highs. These ratios cannot be used as stand-alone predictors of an election but perhaps they can give us a glimpse into voter sentiments as we count down toward the election in November.

A mid-year 2023 Gallup poll found that almost half of Democrats were becoming more hopeful about their personal finances. Republicans and self-identified Independents expressed little confidence at that time. As inflation eased in the second half of 2023, December’s monthly survey of consumer sentiment conducted by the U. of Michigan indicated an improving sentiment among Republicans. The surprise is that there was little change in the expectations of Independents, who now comprise 41% of voters, according to Gallup. There is a stark 30 point difference in consumer sentiment between Democrats and the other two groups. A recent paper presents evidence that the economic expectations of voters shift according to their political affiliations. A Republican might have low expectations when a Democrat is in office, then quickly do an about face as soon as a Republican President comes into office.

Shelter is the largest expense in a household budget. Prudential money management uses personal income as a yardstick. According to the National Foundation for Credit Counseling, the cost of shelter should be no more than 30% of your gross income. Shelter costs include utilities, property taxes or fees like parking or HOA charges. Let’s look at an example in the Denver metro area where the median monthly rate for a 2BR apartment is $1900. Using the 30% guideline, a household would need to gross $76,000 a year. In 2022 the median household income in Denver was $84,000, above the national average of $75,000. At least in Denver, median incomes are outpacing the rising cost of shelter. What about the rest of the country?

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) calculates an Employment Cost Index that includes wages, taxes, pension plan contributions and health care insurance associated with employment. I will use that as a yardstick of income. The BLS also builds an index of shelter costs. Comparing the change in the ratio of shelter costs to income can help us understand why households might feel pinched despite a softening of general inflation in 2023. In the graph below, a rise of .02 or 2% might mean a “pinch” of $40 a month to a median household, as I show in the notes.

Biden and Trump began their terms with similar ratios, although Biden’s was slightly higher. Until the pandemic in early 2020, housing costs outpaced income growth. Throughout Biden’s first year, the ratio stalled. Some states froze rent increases and most states did not lift their eviction bans until the end of July 2021. In 2022, rent, mortgage payments and utility costs increased at a far faster pace than incomes. Look at the jump in the graph below.

An economy is broader than any presidential administration yet voters hold a president accountable for changes in key economic areas of their lives. Food is the third highest category of spending and those costs rose sharply in relation to income.

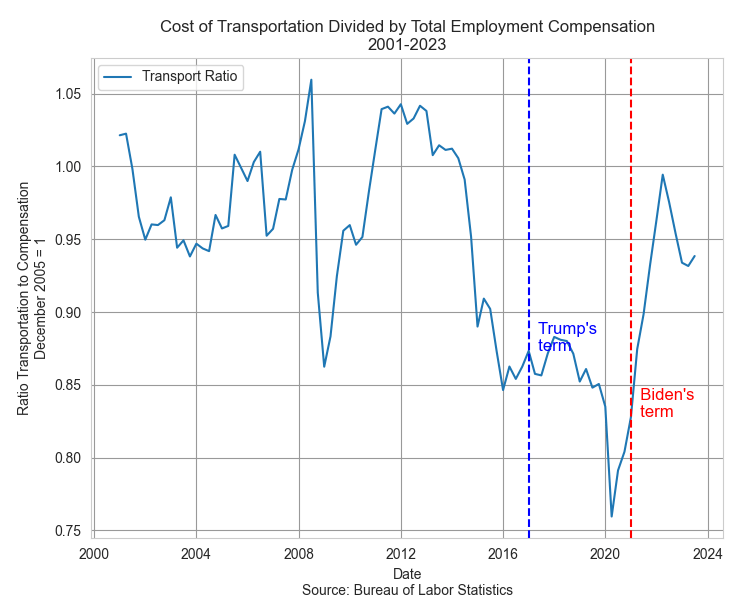

Transportation costs represent the second highest category of spending. These costs have risen far less than income but what people notice are changes in price, particularly if those changes happen over a short period of time. In the first months of the pandemic during the Trump administration, refineries around the world shut down or reduced production. A surge in demand in 2021 caused gas prices to rise. Despite the rise, transportation costs are still less of a burden than they were during the Bush or Obama presidencies.

Neither Biden nor Trump were responsible for increased fuel costs but it happened on Biden’s “watch” and voters tend to hold their leaders responsible for the price of housing, gas and food. In the quest for votes, a presidential candidate will often imply that they can control the price of a global commodity like oil. The opening of national monument land in Utah to oil drilling has a negligible effect on the price of oil but a president can claim to be doing something. Our political system has survived because it encourages political posturing but requires compromise and cooperation to get anything done. This limits the damage that can be done by 535 overconfident politicians in Congress.

Voters have such a low trust of Congress that they naturally pin their hopes and fears on a president. Some are single-issue voters for whom economic indicators have little influence. For some voters party affiliation is integrated with their personal identity and they will ignore economic indicators that don’t confirm their identity. Some voters are less dogmatic and more pragmatic, but respond only to a worsening in their economic circumstances. Such voters will reject an incumbent or party in the hope that a change of regime will improve circumstances. Even though economic indicators are not direct predictors of re-election success they do indicate voter enthusiasm for and against an incumbent. They can help explain voter turnout in an election year. A decrease in these ratios in the next three quarters will mean an increase in the economic well-being of Biden supporters and give them a reason to come out in November.

///////////

Photo by Money Knack on Unsplash

Keywords: food, transportation, housing, shelter, income, election

You can view all three ratios here at the Federal Reserve’s database

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1ejaY

Example: A household grosses $80,000 income including employer taxes and insurance. They pay $24,000 in rent, or 30% of their total gross compensation. Over a short period of time, their income goes up 8% and their rent goes up 10%. The ratio of the shelter index to the income index has gone up from 1 to 1.0185 (1.10 / 1.08). The increase in income has been $6400; the increase in annual rent has been $2400. $2400 / $6400 = 37.5% of the increase in income is now being spent on rent, up from the 30% before the increase. Had the rent and income increased the same 8%, the rent increase would have been only $1920 annually, not the $2400 in our example. That extra $480 in annual rent is $40 a month that a family has to squeeze from somewhere. They feel the pinch.