The manufacturing sector accounts for less than 20% of the economy but is probably the major cause of business cycles in the economy. In the 1990s, the growing development of technology and business services in the U.S., together with what was called “just in time” inventory management, led some economists to declare an end to the business cycle. Cue the loud guffaws.

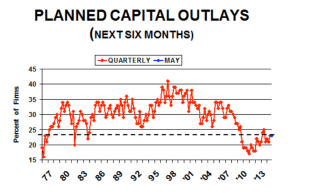

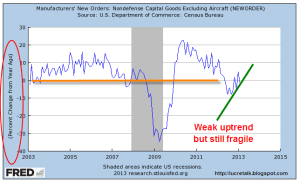

The latest data for non-defense capital goods excluding aircraft from the U.S. Dept of Commerce showed an uptick after a period of decline in the latter half of 2012; however, there is a month lag in this data set.

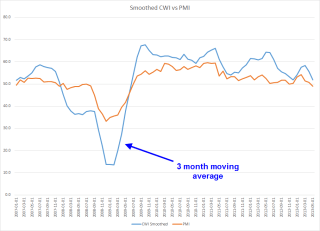

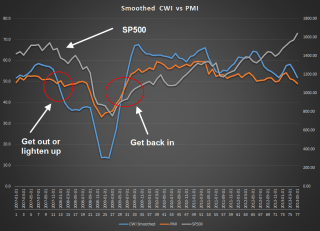

In a 2003 paper, economist Rolando Pelaez tested an alternative model of the Purchasing Managers Index that would better predict business cycles, specifically the swings in GDP growth. Assigning varying constant weights to several key components of the overall PMI index, his Constant Weighted Index (CWI) model is more responsive to changes in business conditions and expectations. In early 2008, the PMI showed mild contraction but Pelaez’ CWI model began a nose dive. It would be many months before the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) would mark the start of a recession in December 2007 but the CWI had already given the indication. In May of 2009, the CWI reversed course, crossing above the PMI to indicate the end of the contractionary phase of the recession. It would be much later that the BEA would mark the recession’s end as June 2009.

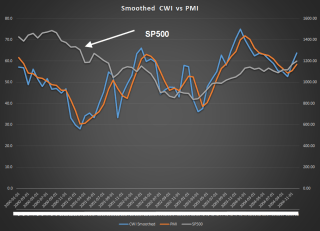

The CWI index is rather erratic. We lose a bit of its ability to lead the PMI when we smooth it with a three month moving average but the trend and turning points are more apparent in a graph.

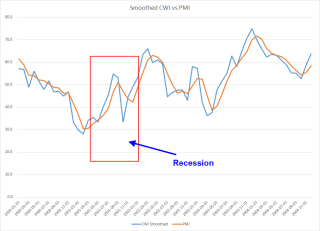

Let’s look at the last six years. In December 2007, the smoothed CWI crossed below the PMI, which was at a neutral reading of about 50. The stock market had faltered for a few months but as 2008 began, the CWI indicated just how weak the underlying economy was. The NBER would eventually call the start of the recession in December 2007. In June 2009, the CWI crossed back above the PMI. Coincidentally, the NBER would later call this the end of the recession.

The period 2000 – 2004 was a seesaw of broken expectations, making it a difficult one to predict because it was, well, unpredictable. I did not show this example first because this period is a difficult one for many indicators. Before 9-11, we were already in a weak recession. Although the official end was declared in November 2001, the effects were long lasting, a preview of what this last recession would be. In 2002, we seemed to be pulling out of the doldrums but the prospect of an Iraq invasion and a general climate of caution, if not fear, prompted concerns of a double dip recession.

The present day reading of both the CWI and PMI are at the neutral reading of 50. Given the rather lackluster growth of the manufacturing sector, the robust rise of the stock market since last November indicates just how much the market is riding on expectations and predications of the future decisions of the Federal Reserve regarding future bond purchases and interest rates. Over the past thirteen years, when the year over year percent change in the stock market hits about 22%, the percentage of growth in the index declines.