January 15, 2023

by Stephen Stofka

For millennia people have claimed a power of divination by various methods, including the casting of bird bones on the ground, the magic of numbers or certain word incantations. As the New Year begins, there is no shortage of predictions for 2023. Will the Fed taper its rate increases now that inflation has moderated? Will the U.S. go into a recession? Will falling home prices invite a financial crisis like the one in 2007-9? Will bond prices recover this year? Other animals see only a few moments into the future. We have developed forecasting tools that try to time-travel weeks and months into the future, but we should not judge a tool’s accuracy by its sophistication.

Statistics is a series of methods that constructs a formula explaining a relationship between variables. Each data point requires a calculation, a tedious task for human beings but a quick operation by a computer. Before the introduction of the computer in the mid-20th century, investors used simpler tools like the comparison of two moving averages of a time series like stock prices. These simple tools are still in use today. An example is the MACD(12,26) trend that compares the 12-day and 26-day moving averages, noting those points where the short 12-day average crosses the long 26-day average (Stockcharts.com, 2023). We can apply a similar technique to the unemployment rate.

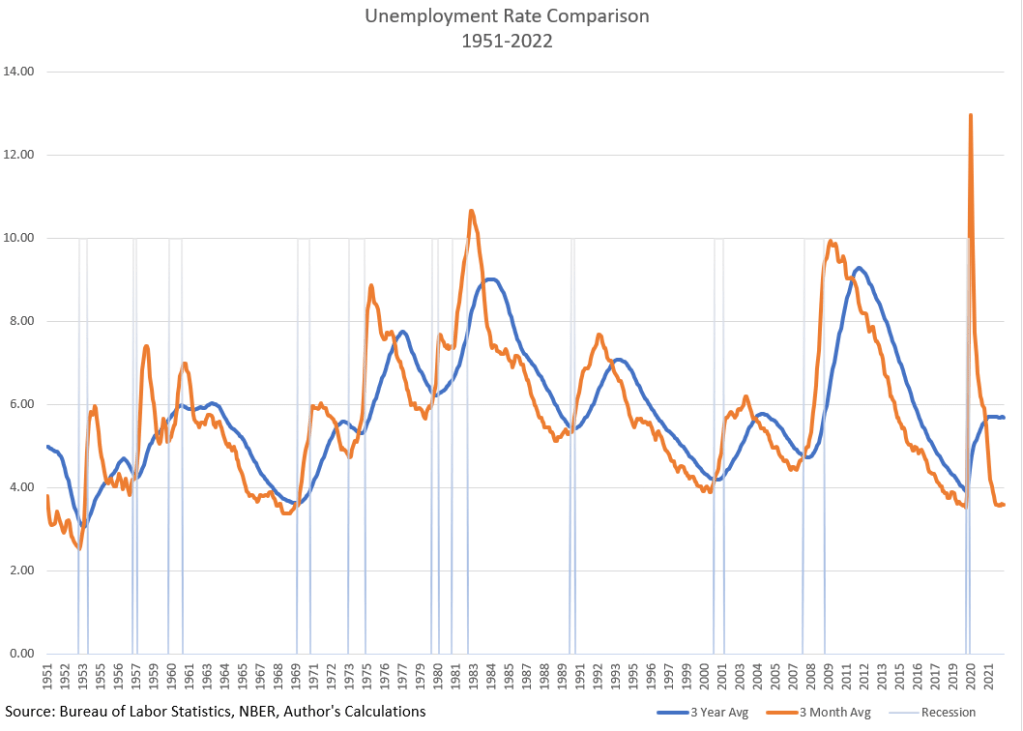

In the chart below I have graphed the 3-month and 3-year moving averages of the headline U-3 unemployment rate. The left side of each column faintly marked in gray marks the beginning of a recession has noted by the NBER (2023). These beginnings roughly coincide with the crossing of the 3-month (orange) above the 3-year (blue) average. With the exception of the 1990 recession, the end of the recessions is near the peak of the 3-month orange line, after which unemployment declines. Today’s 3-month average is well below the 3-year trend, making a recession less likely. However, except for the pandemic surge of unemployment, the 3-month average is quite low and has been below the 3-year average for the longest period in history.

I did not do any laborious trial and error of various averages to find a fit. I chose these periods because they fit my story, something I wrote about last week. A 3-year average should provide a stable long term trend line of unemployment. A 3-month average should reflect current conditions with some of the data noise removed. The crossing should capture an inflection point in the data.

The low unemployment rate implies that workers have more wage bargaining power but wage increases have lagged inflation, robbing workers of purchasing power. If inflation continues to decline in 2023, some economists predict that wage increases may finally “catch up” and surpass the inflation rate.

There are two trends that have weakened the wage bargaining power of workers. Since World War 2, an economy dominated by manufacturing has transitioned to a service economy with lower average wages. In that time, the percent of workers employed in agriculture fell from 14% to less than 2% as production and harvesting became more mechanized. The labor market has undergone structural changes that may invalidate or weaken the lessons of earlier decades.

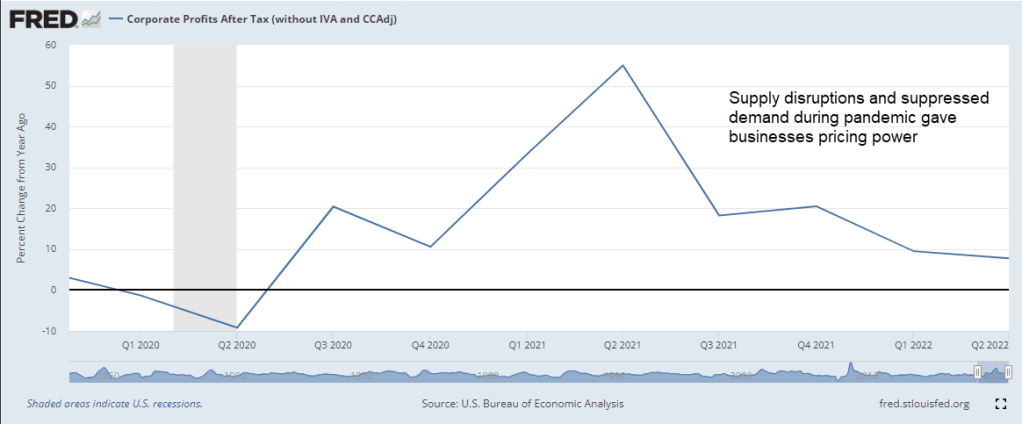

Since WW2, self-employment has declined. Half of those employed now work for large companies with 500 or more employees (Poschke 2019, 2). Few are unionized and able to bargain collectively for wages. According to the Trade Union Dataset (2023), most European countries enjoy much higher trade union participation than in the U.S. where only 10% of workers belong to a union. Large American companies enjoy a wage-setting power that smaller companies do not have and this enables them to resist wage demands. American workers do not have enough wage bargaining power to make a significant contribution to rising prices. Stock owners, able to move money at the stroke of a computer key, hold more bargaining power.

To keep their stock prices competitive, publicly traded companies must maintain a profit margin appropriate to their industry. Investors will punish those companies who do not meet consensus expectations. Company executives rarely take responsibility for falling profit margins. Instead, they blame rising wages or material costs, shifting consumer tastes or government regulations. Interest groups like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, a private lobbying organization funded by the largest companies in America, champion a narrative that inflation is the result of rising wages, not rising profit margins. Like any interest group, their job is to assign responsibility for a problem to someone else, to convince lawmakers to act favorably to their cause or industry. The Chamber has far better funding than advocates for labor and it uses those funds to block policies that might favor workers.

There are economists and policymakers who still believe in the Phillips Curve, a hypothetical inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation. High unemployment should coincide with low inflation and high inflation with low unemployment. Shortly after Bill Phillips published his data and hypothetical curve, Guy Routh (1959), a British economist, published a critique in the same journal Economica, pointing out the flaws in Phillips’ methodology. The chief flaw was Phillips’ lack of knowledge about the labor market itself. Despite that, American economists like Paul Samuelson, who favored an activist fiscal policy, liked the implications of a Phillips Curve. Policy makers could fine tune an economy the way a car mechanic tuned a carburetor.

In the past year, some economists and policymakers have advocated policies to drive unemployment higher and wring inflation out of the economy. Despite rising interest rates, the labor market has been strong and resilient. In January 2020, Kristie Engemann (2020), a coordinator at the St. Louis Fed, explored the debate about whether this relationship exists or not. For the past five decades, the “curve” has been flat, a statistical indication that there is no relationship between inflation and unemployment. Policymakers will continue to cite the Phillips Curve because it serves an ideological and political purpose.

We don’t need statistical software to debunk the Phillips curve. In the chart I posted earlier, there were several points where the 3-month average unemployment rate was near or below 4%. These were in the late 1960s, the late 1990s, and the late 2010s. The inflation rate was 3%, 2.5%, and 1.4% respectively. If the Phillips Curve relationship existed, inflation would have been much higher.

As our analytical tools become more sophisticated we risk being fooled by their power. With a few lines of code, researchers can turn the knobs of their statistical software machines until they reach a result that is publishable. We should be able to approximate if not confirm our hypothesis with simpler tools.

///////////////////

Photo by Augustine Wong on Unsplash

Engemann, K. M. (2020, January 14). What is the Phillips curve (and why has it flattened)? Saint Louis Fed Eagle. Retrieved January 13, 2023, from https://www.stlouisfed.org/open-vault/2020/january/what-is-phillips-curve-why-flattened

National Bureau of Economic Research. (2022). Business cycle dating. NBER. Retrieved January 13, 2023, from https://www.nber.org/research/business-cycle-dating

Poschke, M. (2019). Wage employment, unemployment and self-employment across countries. SSRN Electronic Journal, (IZA No. 12367). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3401135

Routh, G. (1959). The relation between unemployment and the rate of change of money wage rates: A comment. Economica, 26(104), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.2307/2550867

Stockcharts.com. (2023). Spy – SPDR S&P 500 ETF. StockCharts.com. Retrieved January 13, 2023, from https://stockcharts.com/h-sc/ui?s=spy Below the price chart is the MACD indicator pane.

Trade Union Dataset. OECD.Stat. (2023, January 13). Retrieved January 13, 2023, from https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TUD

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Level [CE16OV], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CE16OV, January 11, 2023.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Level – Agriculture and Related Industries [LNS12034560], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LNS12034560, January 11, 2023.

////////////////////