July 10, 2022

by Stephen Stofka

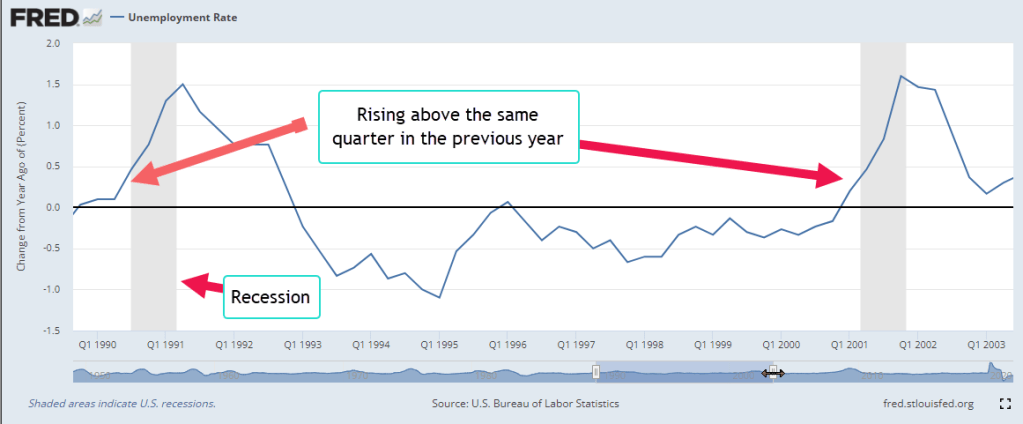

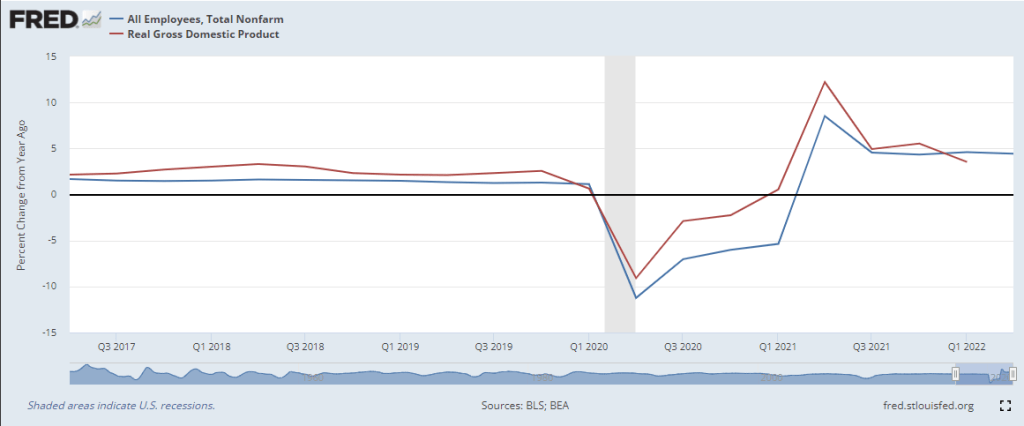

The jobs report this past Friday surprised to the upside, showing a monthly gain of 372,000 jobs, far above the 250,000 expected gain. This is one of three indicators I wrote about last week. The positive job gains lowers the chances of a coming recession but the Atlanta Fed is now projecting a 2nd quarter decline of 2% in real GDP. As some economists have noted, it is unusual to have strong positive employment growth and negative GDP growth. In the graph below is the percent change in employment (blue line) and real GDP (red line). Since labor accounts for the majority of production costs, the two series move closely together.

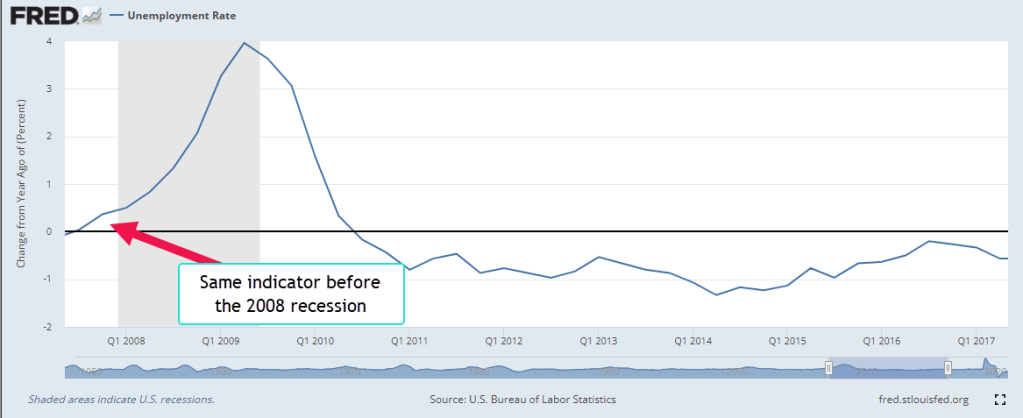

Historically, employment growth (blue line) is declining before recessions. Here is a look at the period before the 2008-9 recession.

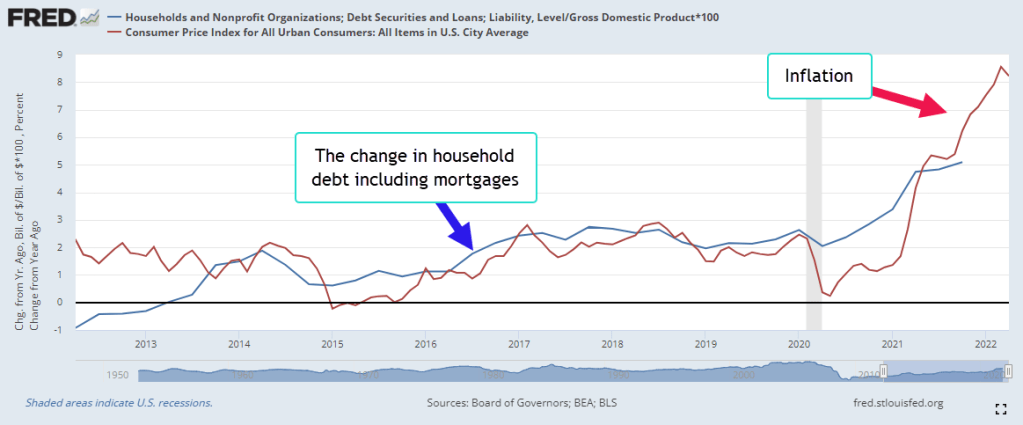

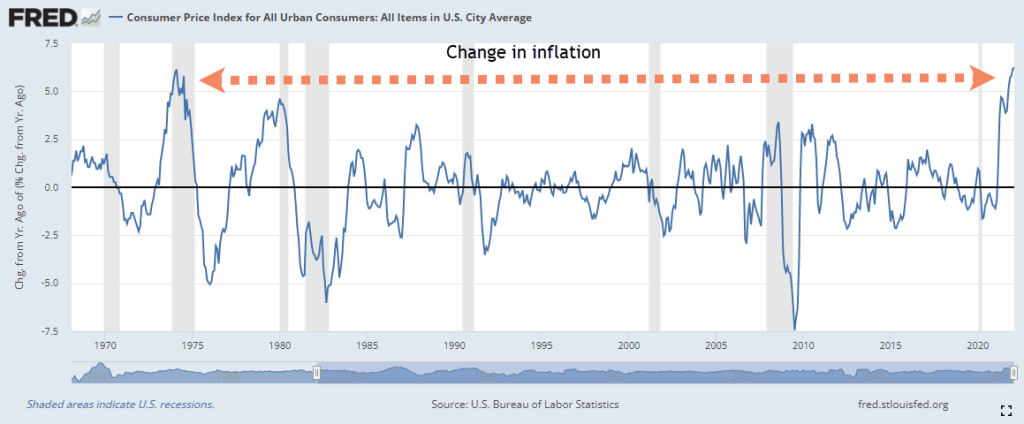

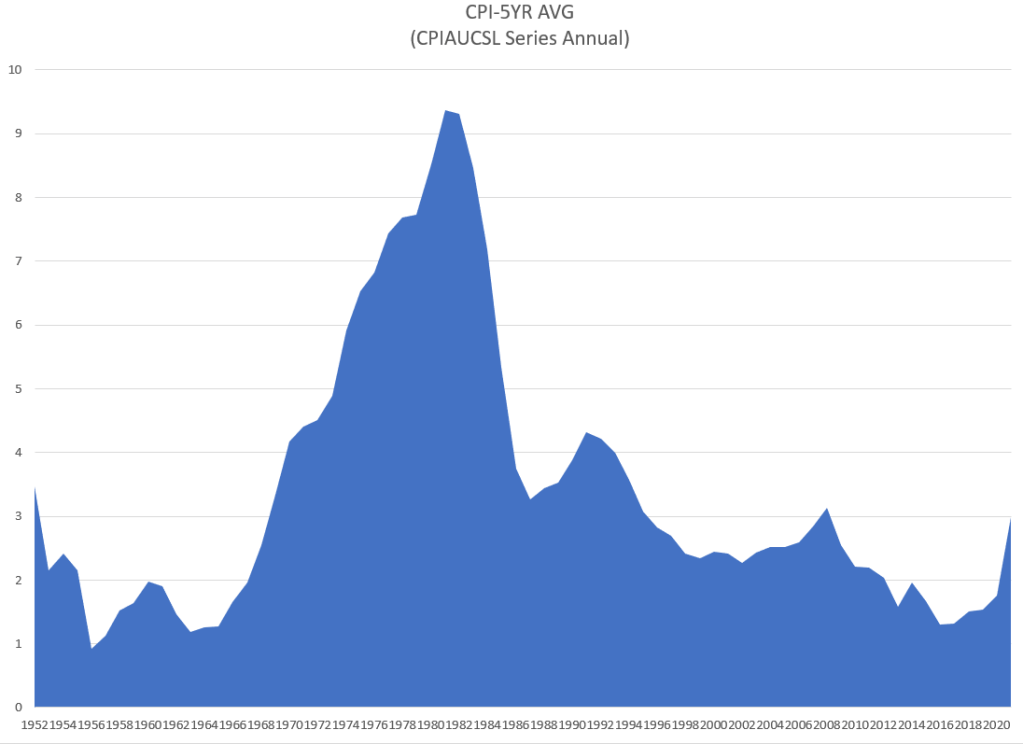

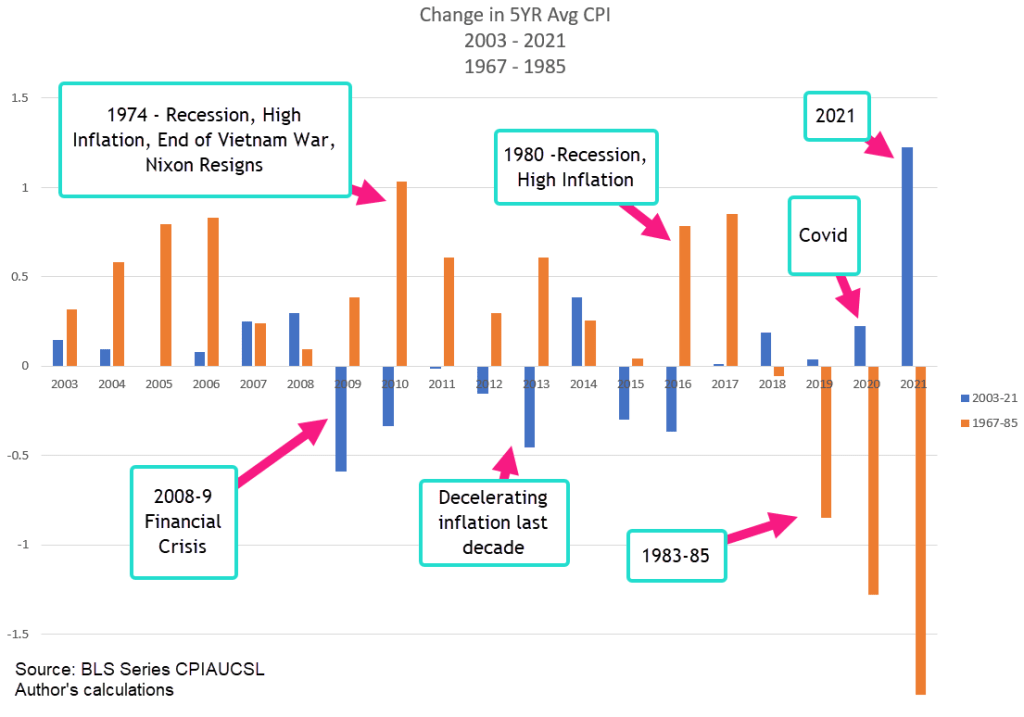

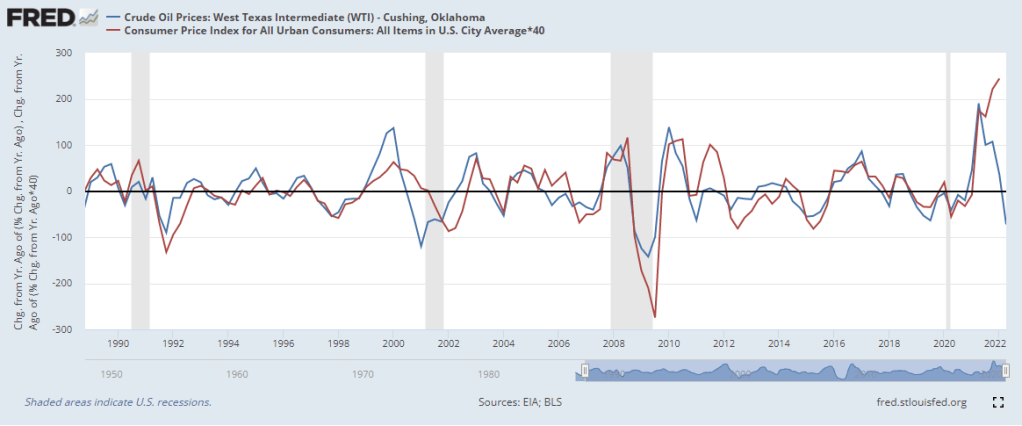

Let’s turn to another prominent concern – inflation. When the price of oil declined below $100 this past week, some economists interpreted that as a sign of decreased demand and a greater likelihood of recession. The price of oil factors into the production of most goods, even the electricity that comes into our homes. In the graph below I’ve charted the acceleration in the price of oil and prices in general. The magnitude is less important than the direction. Most of the time, the direction of each is the same.

Now I want to focus on recent years. As the economy recovered from pandemic restrictions in 2021, the changes in both series shot higher as expected. In the past year, the acceleration in oil prices (blue line) has declined while the acceleration in general prices has gone up.

The divergence is unusual and indicates that inflation is grounded more in supply disruptions and pent up demand than in the price of oil. I’m guessing that the Fed has noticed a similar trend. To appreciate how unusual this divergence is, let’s go back to the 1970s when the price of a barrel of oil went from $3 to $34. Even though the price movement was extreme, the acceleration in oil prices and the general price level moved in the same direction.

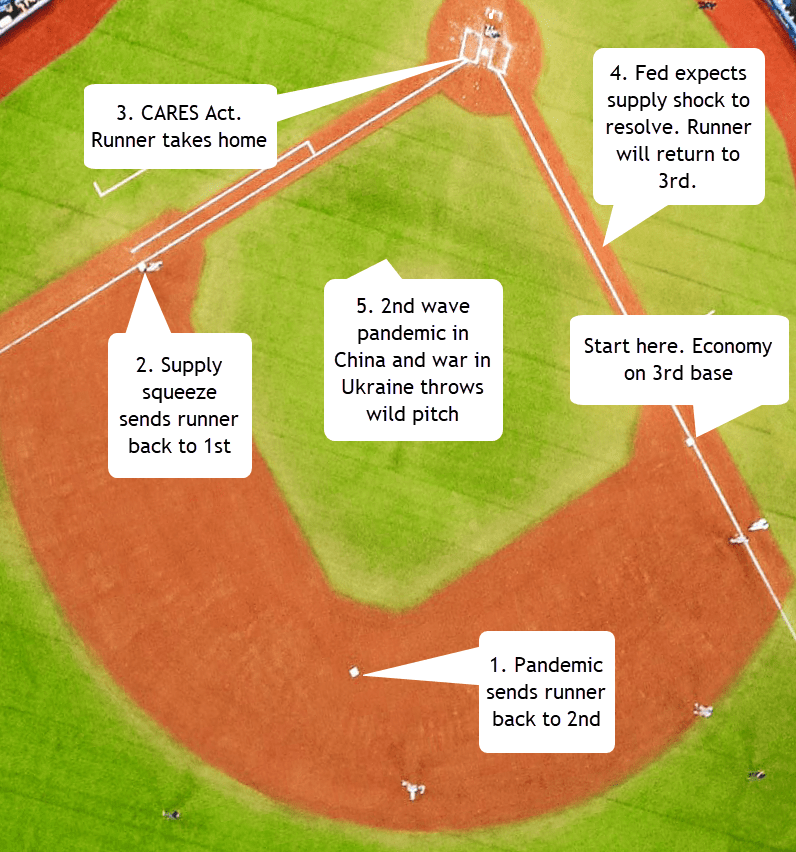

There is no shortage of opinions about Fed monetary policy and the Biden administration’s fiscal policy. The second stimulus payments went out in the first two weeks of 2021 under the Trump administration. Retail sales rose 5% that month, but fell 2% in February. Inflation in February was 1.7%, below the Fed’s target of 2%. On March 11, 2021, six weeks after taking the oath of office, Joe Biden signed the American Rescue Plan and in late March a third round of stimulus payments went out. Retail sales rose 11% in March but most of that increase happened before people received their payment. The odd thing is that there was little change in retail sales in the following months. This is one of many oddities surrounding this pandemic.

The general adult population received vaccines in April, May and June. Inflation rose above 5% by June 2021, then leveled off through September. In the graph above, the acceleration in oil prices and the general price level began to show a divergence. In the last three months of 2021, inflation started climbing while the acceleration in oil started falling. Why? It had never happened before.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has aggravated the situation and no one is happy. Xcel Energy, the public utility in my area, has raised electricity prices by 42% over last year; natural gas prices by 14%. The Fed’s next FOMC meeting is July 26-27 and the market is pricing in a 97% chance that the Fed will raise interest rates by another .75%, moving the federal funds effective rate near 2%. From 1954-2008, the average rate was 5.65%. From 1988-2008, the rate averaged 4.71%. Since 2008, the rate has averaged .62%. Near zero interest rates are abnormal.

Can the Fed retrain investors and consumers expectations toward a 3-4% federal funds rate in line with historical averages? The Fed conducts a lot of research but the current circumstances are unusual and the data shows conflicting trends. In a few years with the benefit of hindsight and firm, revised data, an economist can devote a few chapters if not an entire book to the past two years.

///////////

Photo by Tim Johnson on Unsplash