November 8, 2015

There is the famous Tarzan yell by Carol Burnett and the iconic “Oh my Gawd” exclamation of Janice Lipman in the long running TV series “Friends.” That’s what Janice would have said when October’s employment report was released this past Friday.

Highlights:

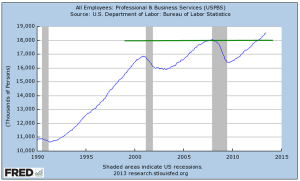

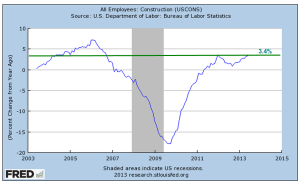

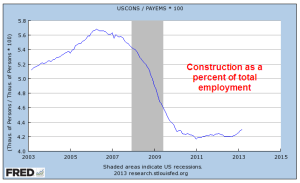

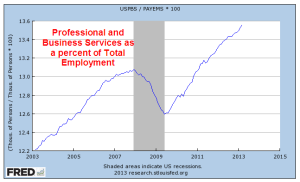

271,000 jobs gained – maybe. That was almost twice the number of job gains in September (137,000). Really??!! ADP reported private job gains of 182,000. Huge difference. Job gains in government were only 3,000 so let’s use my favorite methodology, average the two and we get 228,000 jobs gained, awfully close to the average of the past twelve months. Better than average gains in professional business services and construction. Both of these categories pay well. Good stuff.

At 34.5 hours, average hours worked per week has declined by 1/10th of an hour in the past year. The average hourly rate rose 2.5%, faster than headline inflation and giving some hope that workers are finally gaining some pricing power in this recovery.

For some historical perspective, here is a chart of monthly hours worked from 1921 to 1942. Most of those workers – our parents and grandparents – have passed away. At the lows of the Great Depression people still worked more hours than we do today. They were used to hard work. There were few community resources and social insurance programs to rely on.

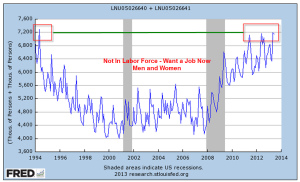

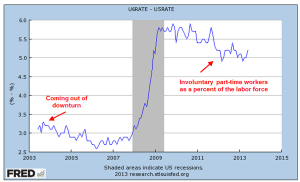

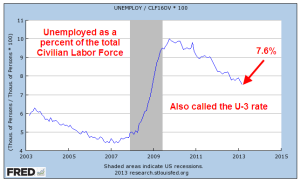

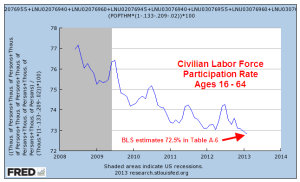

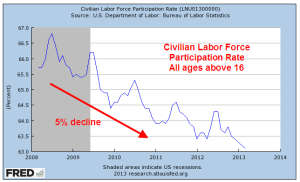

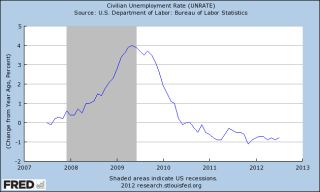

The headline unemployment rate fell slightly to 5%. The widest unemployment rate, or U-6 rate, finally fell below 10% to 9.8%, a rate last seen in May 2008, more than seven years ago. This rate includes people who are working part time because they can’t find a full time job (involuntary part-timers), and those people who have not actively looked for a job in the past month but do want a job (discouraged job seekers). Macrotrends has an interactive chart showing the three common unemployment rates on the same chart.

The lack of wage growth during this recovery, coupled with rising home prices, may have made owning a home much less likely for first time buyers. The historical average of new home buyers is 40%. The National Assn of Realtors reported that the percentage is now 32%, almost at a 30 year low.

2.5% wage growth looks a bit more promising but the composite LMCI (Labor Market Conditions Index) compiled by the Federal Reserve stood at a perfect neutral reading of 0.0 in September. The Fed will probably update the LMCI sometime next week. This index uses more than twenty indicators to give the Fed an in-depth reading of the labor market.

**********************************

Bonds and Gold

The strong employment report increased the likelihood that the Fed will raise interest rates at their December meeting and this sent bond prices lower. A key metric for a bond fund is its duration, which is the ratio of price change in response to a change in interest rates. Shorter term bond funds have a smaller duration than longer term funds. A short term corporate bond index like Vanguard’s ETF BSV has a duration of 2.7, meaning that the price of the fund will decrease approximately 2.7% in response to a 1% increase in interest rates. Vanguard’s long term bond ETF BLV has a duration of 14.8, meaning that it will lose about 15% in response to a 1% increase in rates. In short, BLV is more sensitive than BSV to changes in interest rates. How much more sensitive? The ratio of the durations – 14.7 / 2.7 = 5.4 meaning that the long term ETF is more than 5 times as sensitive as the short term ETF.

What do we get for this sensitivity, this higher risk exposure? A higher reward in the form of higher interest rates, or yield. After a 2.5% drop in the price of long term bond funds this week, BLV pays a yield close to 4% while BSV pays 1.1%. The reward ratio of 4 / 1.1 = 3.6, less than the risk ratio. On September 3rd, the reward ratio was much lower, approximately 3.27 / 1.3 = 2.5, or half the risk ratio.

Professional bond fund managers monitor these changing risk-reward ratios on a daily basis. Retail investors who simply pull the ring for higher interest payments should be aware that not even lollipops at the dentist’s office are free. Higher interest carries higher risk and duration is that measure of risk.

The prospect of higher interest rates has put gold on a downward trajectory with no parachute since mid-October. A popular etf GLD has lost 9% and this week broke below July’s weekly close to reach a yearly low. Investors in gold last saw this price level in October 2009. Back then gold was continuing a multi-year climb that would take its price to nosebleed levels in August 2011, 70% above its current price level.

**********************************

CWPI (Constant Weighted Purchasing Index)

Manufacturing is hovering at the neutral 50 mark in the ISM Purchasing Manager’s Index but the rest of the economy is experiencing even greater growth after a two month lull. No doubt some of this growth is the normal pre-Christmas hiring and stocking of inventories in anticipation of the season.

The CWPI composite of manufacturing and service sector activity has drifted downward but is within a range indicating robust growth.

Employment and New Orders in the non-manufacturing sectors – most of the economy – rose up again to the second best of the recovery.

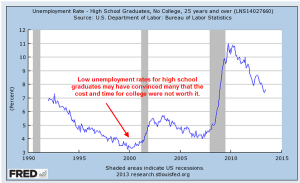

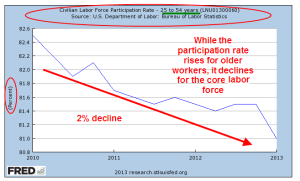

Economists have struggled to build a mathematical model that portrays and predicts the rather lackluster wage growth of this recovery in a labor market that has been growing pretty strongly for the past few years.

*************************************

Social Security

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, passed and signed into law this past week, curtails or eliminates a Social Security claiming strategy that has become popular. (Yahoo Finance – can pause the video and read the text below the video). These were used by married couples who were both at full retirement age. One partner collected spousal benefits while the “file and suspend” partner allowed their Social Security benefits to grow until the maximum at age 70. On the right hand side of this blog is a link to a $40 per year “calculator” that helps people maximize their SS benefit.

************************************

Tax Cuts Anyone?

Former Senator, Presidential contender and actor Fred Thompson died this past week. The WSJ ran a 2007 editorial by Thompson arguing that the “Bush tax cuts” that the Republican Congress passed in 2001 and 2003, when he was a Senator, had spurred the economy, causing tax revenues to increase, not decrease, as opponents of the tax cuts claimed. Like others in the tax cut camp, Thompson looked at a rather small slice of time to support his claim: 2003 -2007.

Had tax cut advocates looked at an earlier slice of time – also small – in the late 1990s they would have seen the opposite effect. Higher tax rates in the 1990s caused greater economic growth and higher tax revenues to the government, thereby shrinking the deficit entirely and producing a surplus.

Tax cuts decrease revenues. Tax increases increase revenues. That tax cuts or increases as enacted have a material effect on the economy has been debated by leading economists around the world for forty years. At the extremes – a 100% tax rate or a 0% tax rate – these will certainly have an effect on people’s behavior. What is not so clear is that relatively small changes in tax rates have a discernible impact on revenues. A hallmark of belief systems is that believers cling to their conclusions and find data to support those conclusions in the hopes that they can use that to help spread their beliefs to others.

The evidence shows that economic growth usually precedes tax revenue changes; that tax policy advocates in either camp have the cart before the horse. A downturn in GDP growth is followed shortly by a decline in tax revenues.

Thompson’s editorial notes a favorite theme of tax cut advocates – that the “Kennedy” tax cuts, initiated into law in memory of President Kennedy several months after his assassination in November 1963, spurred the economy and increased tax revenues. Revenues did increase in 1964 but the passage of the tax act occurred during that year so there is little likelihood that the tax cuts had that immediate an effect. Revenues in 1965 did increase but fell in subsequent years. A small one year data point is all the support needed for the claims of a believer.

The question we might ask ourselves is why do tax policy and religion share some of the same characteristics?