November 20, 2022

by Stephen Stofka

This week’s letter is about household savings and corporate profits. As a share of GDP, savings are near an all-time low while profits are at an all-time high. Elon Musk, the CEO of Tesla, appeared in court this week. No, this wasn’t about his acquisition of Twitter. It concerned a shareholder lawsuit against Tesla regarding the $50B stock option package the company awarded him in 2018. In 2019 the company’s total revenue – not profit – was less than $25B. In 2022, annual revenue was $75B. At a 15% profit margin, the company must continue growing its revenue at a blistering pace to afford Mr. Musk’s incentive pay package. Large compensation packages like this are only a few decades old. Let’s get in our time machine.

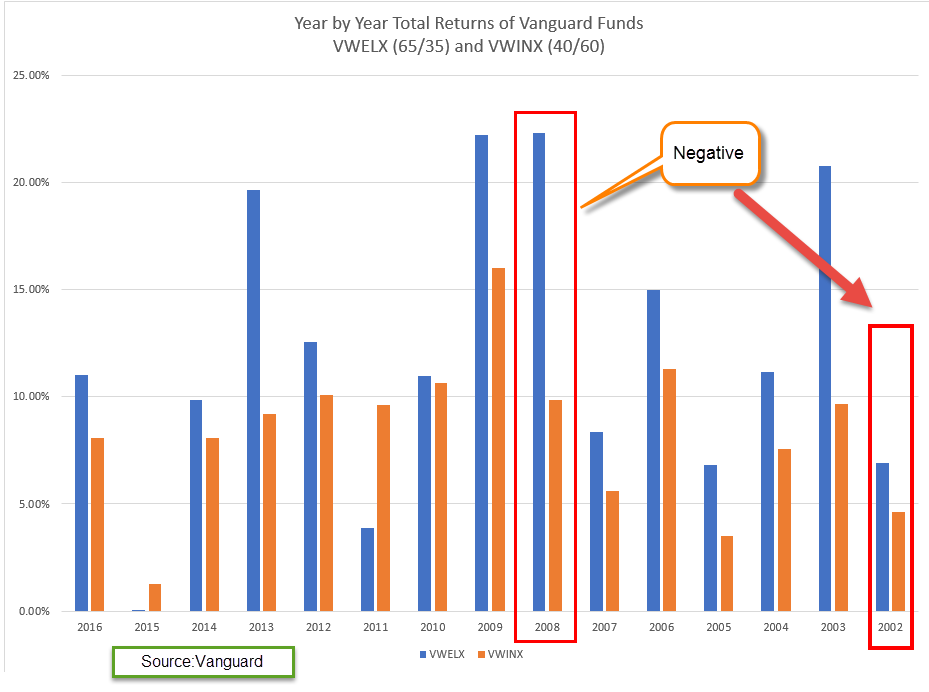

In 1994, Kurt Cobain, the 27 year old leader of the rock group Nirvana, died from an overdose of heroin. Something else was dying that year – corporations were breaking free of national boundaries and moving production to countries other than their home nation. This was the last stage in the evolution of multinational corporations, or MNCs. In earlier decades, companies had licensed or franchised their brand. Perhaps they had set up a sales office in a foreign country. Now they were becoming truly global. Fueling that expansion was an increase in equity ownership by large institutional investors. To accommodate these changes, their governance structures changed. Executives capable of leading this global growth were rewarded on a parallel with superstar sports talent. That was the conclusion of Hall and Liebman (2000, 3), two researchers at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

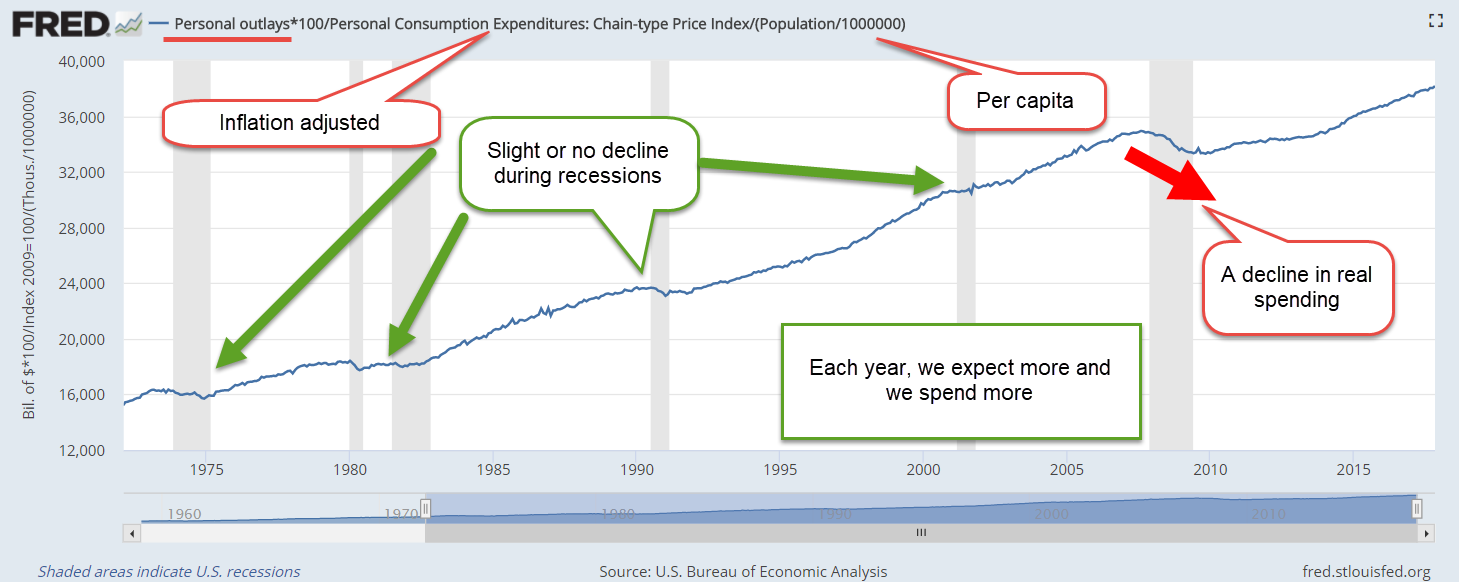

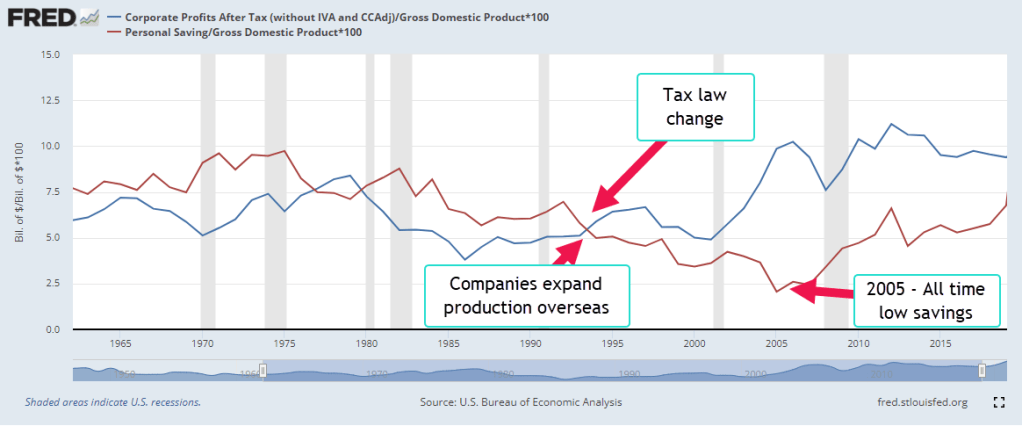

Let’s look at two series over the past sixty years – personal savings and corporate profits. If we think of a household as a small enterprise, personal savings is the residual left over from the household’s labor. Likewise, corporate profits are the residual left over from current production. In 1994, the two series diverged. Corporate profits (the blue line in the graph below) kept rising while personal savings plateaued for a decade. Each series is a percent of GDP to demonstrate the trend more easily.

Executive Compensation

In the mid-1990s, corporations began to issue a lot more stock options to their executives. Some think that a change in the tax code might have precipitated this shift in compensation. In 1994, Section 162m of the IRS code limited the corporate deductibility of executive pay to $1 million (McLoughlin & Aizen, 2018). By awarding non-qualified stock options to their executives, companies could preserve the corporate tax deduction. However, the slight tax advantage did not account for the rapid increase in options awards. Hall and Liebman found that the median executive received no stock option package in 1985. By 1994, most did. The tax change was secondary – a distraction. Institutional investors wanted more growth and more profits and companies were willing to reward executives with compensation packages similar to sports stars (Hall & Liebman, 2000, 5). Some of these superstars included Jack Welch of General Electric, Bill Gates of Microsoft, Michael Armstrong of AT&T.

Income Taxes – Less Savings

In 1993, Congress passed the Deficit Reduction Act that raised the top tax rate from 31% to almost 40%. Personal income tax receipts almost doubled from $545 billion in 1994 to almost $1 trillion in 2001. The booming stock market in the late 1990s produced big capital gains and taxes on those gains. For the first time in decades the federal government had a budget surplus. However, more taxes equals less personal savings so this contributed to the flatlining of personal savings during that period.

Household Debt Supports More Spending

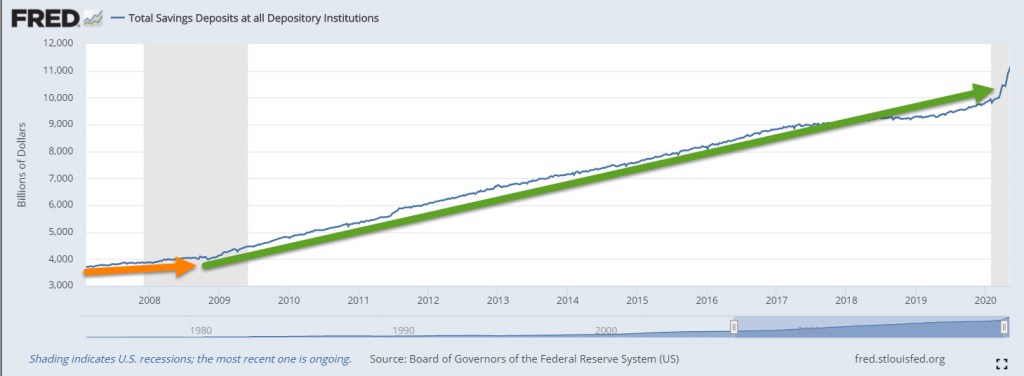

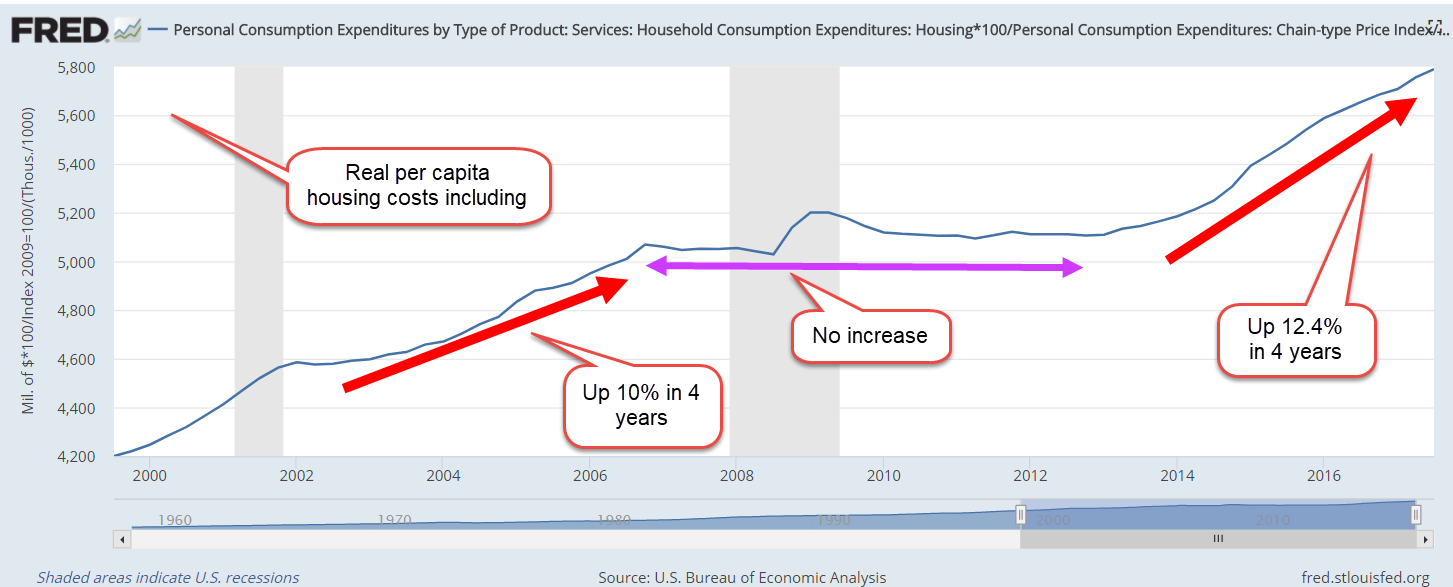

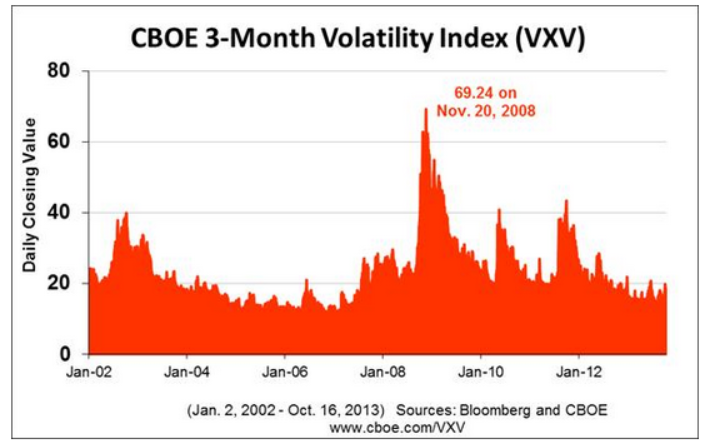

During the 2000s, personal savings remained flat. On an inflation adjusted basis, they were falling. Too many people were tapping the rising equity in their home to pay expenses and economists warned that household debt to income ratios were too high. Savings as a percent of GDP fell to a post-WW2 low. As home prices faltered and job losses mounted in late 2007, people began to save more but their debt left them with little protection against the economic downturn. During 2008, personal savings began to increase for the first time in fifteen years. More savings meant less spending, furthering the economic malaise that began in late 2007.

Multi-National Corporate Profits

During those 15 years corporate profits rose steadily as companies increased their global presence. Beginning in 1994 U.S. companies began shifting production to Mexico where labor was cheaper. In 2001, China was admitted to the World Trade Organization (WTO) and production outsourcing continued to Asia. Despite the profit gains, companies kept their income taxes in check. In 2021, corporate income taxes were at about the same level as in 2004. That contributed to the rising budget deficit during the first two decades of this century.

Federal Deficit

The prolonged downturn in 2001-2003 and the financial crisis and recession of 2007-2009 put a lot of people out of work. This triggered what are called “automatic stabilizers,” unemployment insurance and social benefits like Medicaid, housing and food assistance. The federal government went into debt to pay for the Iraq War, pay benefits to people and help fill the budget gaps in state and local budgets. The tax cuts of 2003 enacted under a Republican trifecta* of government control reduced tax revenues, further increasing the deficit. During George Bush’s two terms, the debt almost doubled from $5.7 trillion to $11.1 trillion.

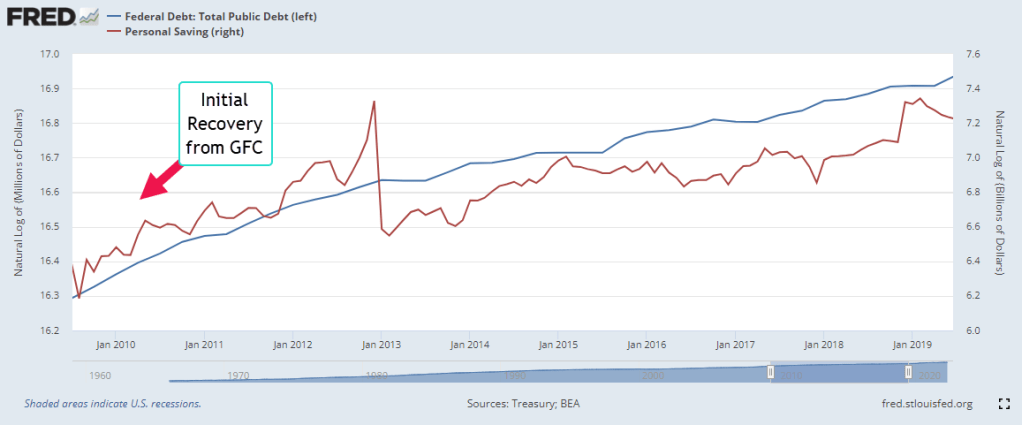

In coping with the recovery from the financial crisis, the government added another $8.7 trillion to the debt. That negative saving by the government helped add to the personal savings of households but too much was spent on just getting by. Following the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), the trend of the government’s rising debt (blue line below) matched the trend in personal savings (red). Sluggish growth and lower tax revenues caused the two to diverge. While the debt grew, personal savings lagged.

Before and During the Pandemic

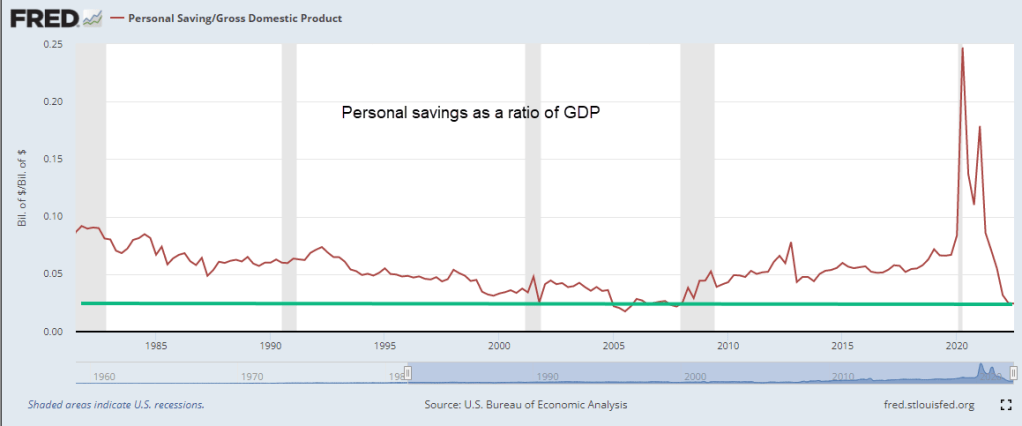

Following the 2017 tax cuts enacted under another Republican trifecta, personal saving rose, then spiked when the economy shut down during the pandemic and the federal government sent stimulus checks under the 2020 Cares Act. In the chart below, notice the spike in debt and savings. By the last quarter of 2020, personal savings had risen by $600 billion from their pre-pandemic level of $1.8 trillion. In late December, President Trump signed the $900 billion Consolidated Appropriations Act (Alpert, 2022) but that stimulus did not show up in personal savings until the first quarter of 2021. In March 2021 President Biden signed the $1.7 trillion American Rescue Plan. Personal savings rose $1.6 trillion in that first quarter, the result of both programs.

After the Pandemic

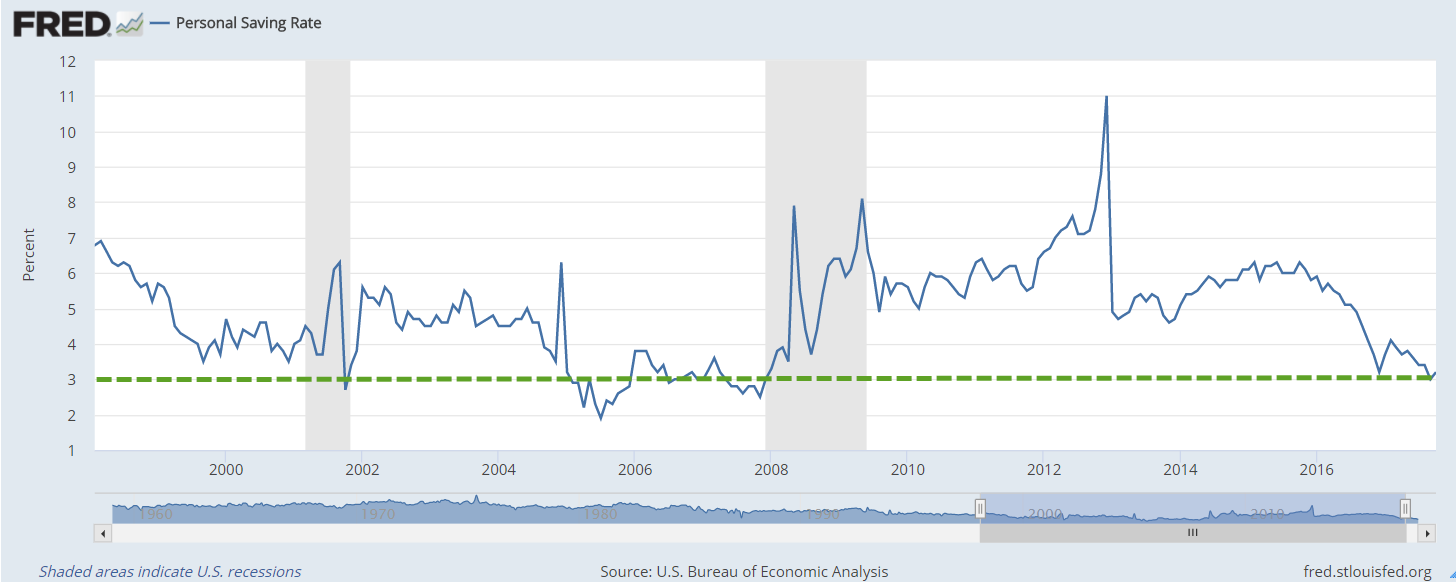

Some economists have said that the American Rescue Plan was too much. In hindsight, it may have been but we don’t make decisions in hindsight. As more schools and businesses opened up, households spent far more than any extra stimulus. They spent $1.2 trillion of savings they had accumulated before the pandemic and savings are now at the same level as the last quarter of 2008 when the financial crisis struck. Thirteen years of cautious savings behavior has vanished in a few years. On an inflation-adjusted basis, personal savings is at a crisis, almost as low as it was in 2005. In the chart below is personal savings as a ratio of GDP.

The Future

In the past year savings (red line) and corporate profits (blue line) have resumed the divergence that began almost three decades ago. Profits were 12% of GDP in the 2nd quarter of 2022. Savings is near that all time low of 2005. Rising profits benefit those of us who own stocks in our mutual funds and retirement plans. However, the divergence between the profit share and the savings share is a sign that the gap between the haves and the have-nots will grow larger.

////////////////////

Photo by Jens Lelie on Unsplash

- A trifecta is when one party controls the Presidency and both chambers of Congress.

Alpert, G. (2022, September 15). U.S. covid-19 stimulus and relief. Investopedia. Retrieved November 19, 2022, from https://www.investopedia.com/government-stimulus-efforts-to-fight-the-covid-19-crisis-4799723. See Stimulus and Relief Package 4 for the December 2020 CAA stimulus. See Stimulus and Relief Package 5 for the American Rescue Plan in March 2021.

Hall, B. J., & Liebman, J. B. (2000, January). The Taxation of Executive Compensation – NBER. National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved November 19, 2022, from https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c10845/c10845.pdf. Interested readers can see Moylan (2008) below for a short primer on the recording of options in the national accounts. Until 2005, these options were recorded as compensation for tax purposes but not recorded on financial statements so they did not initially affect stated company profits.

McLoughlin, J., & Aizen, R. (2018, September 26). IRS guidance on Section 162(M) tax reform. The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. Retrieved November 18, 2022, from https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2018/09/26/irs-guidance-on-section-162m-tax-reform/

Moylan, C. E. (2008, February). Employee stock options and the National Economic Accounts. BEA Briefing. Retrieved November 19, 2022, from https://apps.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2008/02%20February/0208_stockoption.pdf