January 8, 2023

by Stephen Stofka

This week’s letter is about price illusions. The past two weeks I have written about the need to sort through past events to find the lessons. The past is a teacher, not a goal. Those who idealize and revere the past must eventually be swept down the drain of time. During this week’s struggle to elect Kevin McCarthy as House Speaker, the more conservative members of the Republican Party voiced their desire to return the country to the past of more than a hundred years ago when the population of 112,000,000 was a third the current size. Instead of learning from the past, we often use elements of history to tell a story. We discard events that do not fit our narrative. Historical analysis serves political interests. Asset analysis suffers from similar distorting strategies.

Technical analysis studies price movements with little regard for the circumstances that prompted the supply and demand, the buying and selling that underlie those movements. I will pick a few such variants at random. Elliott Wave theory bases its interpretation of price movement on the Fibonacci sequence of numbers. Beginning with 1, 1 this number series is constructed from the sum of the previous two numbers in the series. Thus 1 + 1 = 2, 2+1 = 3, and so on. This simple rule produces a sequence found in plant growth and the development of nautilus shells, for example.

Elliot Wave analysis claims that price movements come in waves. Understanding the current position within a wave can help an investor predict subsequent price action. The system is famously prolific in its prophecy, indicating several interpretations. It is better suited to a post hoc narrative. An investor can believe that if they just got better at interpreting the waves, they could time their buying and selling. As the physicist Richard Feynman said, “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool.”

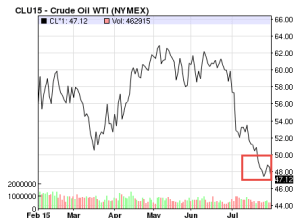

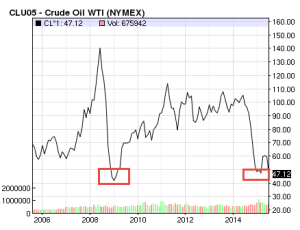

Another technical system relies on the recognition of price trends, identifying those to follow and those that signal a likely reversal. These are visual and geometric, full of rising wedges, head and shoulders price patterns, double tops and bottoms. Much human behavior is repetitive, tempting an investor to perceive a pattern then extend it into the future. The repetition hides the recursive or evolutionary nature of human thinking. Inertia, Newton’s First Law of Motion, may apply to inanimate objects but not to human behavior. Biological systems have built-in dampeners that counteract a stimulus. Without repeated stimulus, the formation of any possible pattern decays.

Price behaves like a biological organism, not an inanimate object. We can see beautiful symmetries in graphical chart analysis but each pattern formation has a unique history. Price is the visible point of a response to events, needs and expectations. Price is a story of people. George Soros, a highly successful investor, constructs a predictive story, then watches price only as a confirmation or refutation of the story. If Soros thinks his story is not unfolding as he predicted, he exits his position.

In school we encountered various branches of mathematics where we were given formulas and plotted data points or intersections, the solutions to a set of equations. Statistics is the reverse of that process. We are given data sets and try to derive formulas to explain relationships within the data. A data set might be the test scores of students before and after the initiation of a certain curriculum. We may represent the test scores on a graph, but the scores reflect a complex set of individual behavior and circumstances, institutional policies, cultural background and economic resources. A statistical analysis tries to include some of these aspects in its findings. A student population is likely more homogenous than the companies in the SP500 stock index who represent a variety of industries. Just as test scores cannot fully explain the efficacy of a school policy or curriculum, asset prices do not reflect the complexity of a day’s events. In our longing for predictability and our fondness of patterns, we prefer analysis that explains price action as a rational sequence of responses to economic, political and financial events. Much financial reporting is happy to oblige.

//////////////////