October 21, 2018

by Steve Stofka

Should a young person invest money in a college education? Let’s look at the question from a financial perspective. Building a higher educational degree is as much an asset as building a house. Let me begin with the hard numbers.

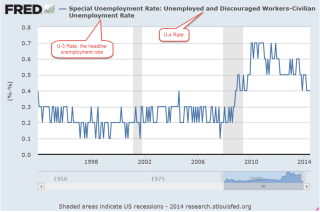

Employment: A person is more likely to be employed. Here is a comparison of those with a four-year degree or higher and those with a high school diploma. The difference in rates is 2% – 3% during good times and as much as 6% during bad times.

Is the unemployment rate enough to justify an investment of $50K or more in a four-year degree? Maybe not. During the worst part of the financial crisis, ninety percent of HS graduates were working. Why should a diligent person with good work skills spend time in college? Most college students take six years to complete a four-year degree. They must spend four to six years of study in addition to the loss of work experience and earnings in those years. The unemployment rate is not a decision closer.

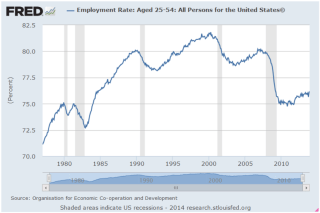

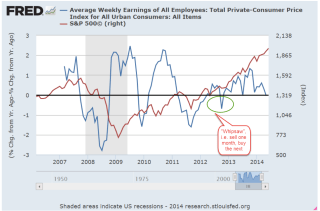

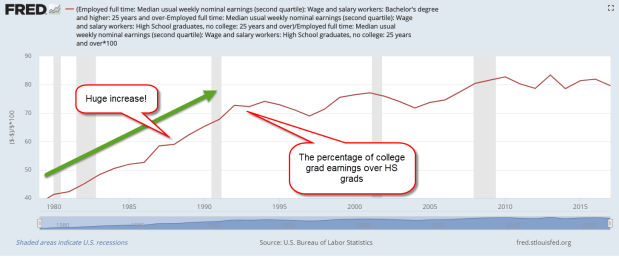

Earnings: In 1980, when those of the Boomer generation were taking their place in the workforce, college grads earned 41% more than HS grads. Today, college grads earn 80% more. That gap of $567 per week totals almost $30,000 in a year and is less than the monthly payment on a $50,000 loan (Note #1). Can a person expect to earn that much additional when they first graduate? No, and that’s why many students struggle with their loan payments in the decade after they graduate.

Maybe that earnings difference is a temporary trend. The debt is permanent. Should a young person take on a lot of debt only to find out the earnings difference between college and high school graduates was temporary? Unfortunately, that’s not the case. The big shift came in the 1980s when the gap in earnings grew from 41% to 72% in twelve years.

There were several reasons for the explosive growth in that earnuings gap. Many Boomers had gone to college to avoid the Vietnam War draft. As they crowded into the workforce in the late 1970s and 1980s, they wanted more money for that education.

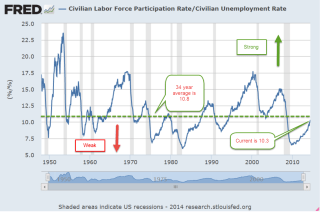

During the 1980s, the composition of jobs changed. Steel manufacturing went overseas to smaller and more nimble plants which could adjust their outputs more economically than the behemoth steel plants that dominated the U.S.

Automobile companies in Michigan closed their old plants. Chrysler needed a government bailout. The manufacturing capacity of Asia and Europe that had been crippled by World War 2 took several decades to recover. The U.S. began to import these cheaper products from overseas. As high-paying blue-collar jobs diminished, the advantage of white-collar workers grew.

As more companies turned to computers and the processing of information, they wanted a more educated workforce that could understand and execute the growing complexity of information. Manufacturing today relies on computer programs that require a set of skills that are more technical than the manufacturing jobs of the past.

A oft-repeated story is that the signing of NAFTA in 1993 and the admittance of China into the World Trade Organization were chiefly responsible for the growing gap between white collar and blue collar workers. I have told that story as well, but it is incorrect and incomplete. As the graph above shows, that gap has grown modestly in the past twenty-five years. The big shift happened in the 1980s when the first of today’s Millennials were in diapers and grade school.

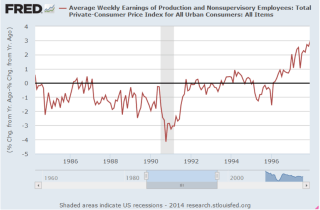

When we adjust weekly earnings for inflation, we can better understand the evolution of this earnings gap. In the past forty years, high school graduates have seen no change in median weekly earnings. From 1980 to 2000, their earnings declined. The 25% growth in the earnings of college graduates came in two spurts: in the mid to late 1980s, and during the dot-com boom of the late 1990s.

Since this trend has been in place for decades, college students can assume that it will likely stay in place for the following few decades. Like the mortgage on a home, the balance on a student loan doesn’t increase every year with inflation, but the earnings from that education do and they have increased more than inflation. The payoff to a four-year degree is the difference in earnings. That is the decision closer.

Notes:

- Using $50,000 loan for ten years at 6% interest rate at Bank Rate.