This past Wednesday the payroll firm ADP released their monthly report of private employment with a rather tepid 119,000, prompting an equally tepid sell off in the market, which lost about .7% by the end of Wednesday. Although the price move was under 1%, the volume of trading was high. Was this the end of the 6+ month run up in stock prices? Was the economy slowing down?

Came Thursday and a very cheery weekly report of new claims for unemployment and moods brightened. The market regained the ground lost Wednesday and then some, but on rather low volume. Standing on the sidewalks of Wall Street, traders repeatedly opened up their umbrellas, then closed their umbrellas, put on their sunglasses, then took off their sunglasses.

[And now a pause from our sponsor. A trader tells his doctor he’s anxious and asks for a prescription. The doctor gives him some advice: “stop looking at the market so much.”]

Back to our story. Friday morning dawned, the heavens opened and the sun shone. The Bureau of Labor Statistics issued its monthly weather – er, labor – report and traders threw down their umbrellas and put on their shades. Huzzahs rang throughout the canyons of lower Manhattan. Some slacker dudes cooly tossed their stocking caps in the air, while men dressed in crisp suits wished that they too had hats.

The labor report is released an hour before the market opens at 9:30 AM. The market opened up 1%, drifted higher but ended the day at about the same price as it opened. So, huh? We’ll get to the huh part later.

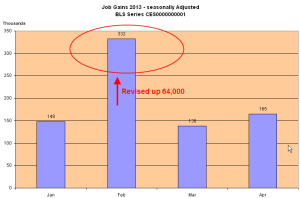

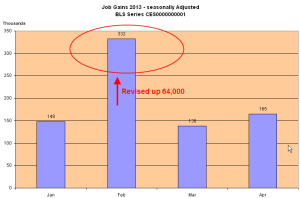

The reported job gains of 165,000 for April were just slightly above the 150,000 jobs consensus estimate and the replacement rate needed to keep up with population growth. Spurring the initial enthusiasm was relief that job gains were not as weak as some had feared (100,000 or so) and the revisions to previous months job gains, adding 114,000 to February and March’s job gains. But February’s revision from strong to very strong job growth provokes some head scratching.

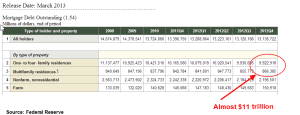

What good things happened in February to inspire such strong job growth? Hmmmm….here’s a table of the past 12 months data from the establishment survey.

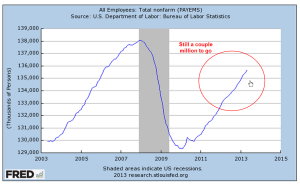

There was a lot to like in this month’s report. The unemployment rate dropped a tenth of a percent to 7.5%. We just passed employment levels of February 2006 – yep, it’s been a slow recovery.

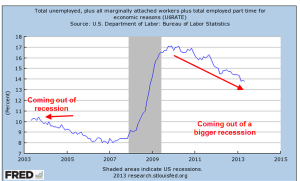

To get the big picture, let’s look at the last forty years.

From this perspective, we can see just how deep the job losses have been since 2008. From this rather sobering point of view, let’s look at some of the positives from this month’s report.

Professional and Business services added a whopping 73,000 jobs this month, far above the 49,000 average of the past 12 months. Restaurant and bar jobs were up 50% above their 12 month average, showing gains of 38,000. Temp help posted strong gains of 31,000, its highest of the past year.

Construction jobs showed little change, a surprise at this time of year. Construction has been averaging gains of 27,000 a month for the past six months. This past week, I spoke to a woman at a Denver branch of a national temp agency. This branch focuses on manual labor, mostly for the construction industry. She confirmed that business has been brisk but most of the calls are for road repair and rebuilding and some commercial construction. When I asked her about calls for helpers and job site clean up for residential construction, she said it had been sporadic.

Job gains in health care were somewhat below their 12 month average of 24,000 but any slack in health care was made up by strong growth in retail. Government jobs continue to contract slightly each month.

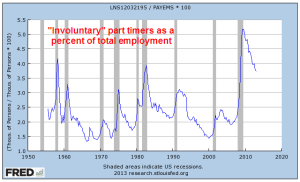

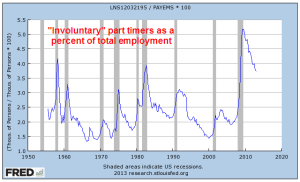

Underlying the positive aspects of the job market are some anemic indicators. The average of weekly hours dropped .2 hour to 34.4; the average has lost .1 hr in the past year. The ranks of the long term unemployed dropped by 258,000 workers but the number of people working part time who would like a full time job jumped 278,000. The ranks of the “involuntary” part timers – those who would like a full time job but can’t find one – is about 5 million. Here’s a surprise. Today’s levels of involuntary part timers as a percent of total employment is only the third highest in the past fifty years; the late 1950s and the early 1980s were worse. But this only means that the ranks of part timers have fallen mercifully from nose bleed levels.

The diffusion index is showing some weakness; this is the share of employers who are reporting job gains vs. job losses, with a value of 50 being neutral. Manufacturing employers are already reporting more job losses than gains. Overall, employers are slowly drifting toward neutral in their hiring for the past several months.

The core work force aged 25 – 54 is still limping along.

Even more disturbing is the participation rate of this core work force.

Shortly after the market opened on Friday came the report on factory orders and it muted some of the enthusiasm generated by the labor report. New orders for durable goods, a barometer of business confidence, fell 5.8%, confirming the slowdown in manufacturing. Employment in this sector has been flat the past two months.

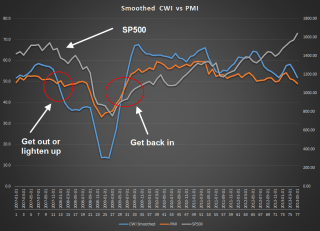

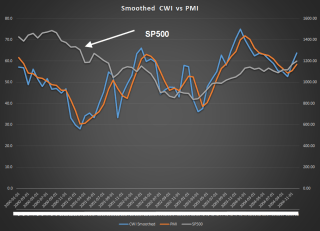

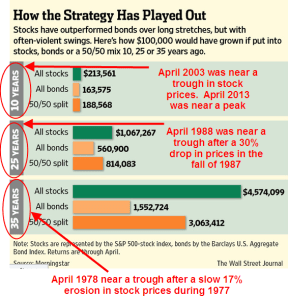

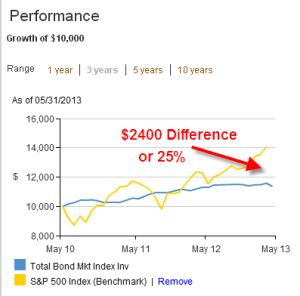

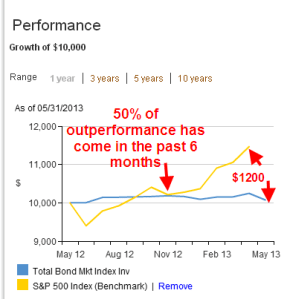

While the monthly labor report makes headlines, it is not a leading indicator. Professional investors watch the squiggles of daily and weekly economic and news reports, trying to anticipate developing trends. Many of us have neither the time or inclination. For the long term “retail” investor, continuing job gains are positive, particularly if they are at or above the replacement level of 150,000. The long term investor is more concerned about significant losses in their retirement portfolio.

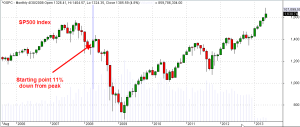

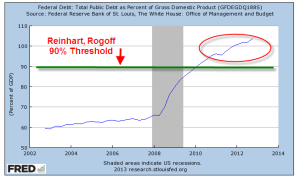

What if an investor lightened up on their stock holdings shortly after the BLS reported the first job losses? I looked back at historical employment releases ; I wanted to use the original releases, not the revised figures of later months, to capture the sentiment at the time. We must make decisions in the present. We don’t have the luxury of going into the future, looking at data revisions, then coming back to the present and making our investing decisions. That would be a good time machine, wouldn’t it? Here’s an example of how employment data can be reported initially and later revised. The graph shows the later revisions.

In early August 2000, the BLS reported job losses of 108,000 in July. But this was due to the layoff of 290,000 temporary Census workers. Do census workers really count in our strategy? Let’s say not. We wait till next month’s report, which shows a loss of 105,000. Should we use our strategy? Again, those darn census workers. Without them, there would have been a small gain in jobs. So we don’t sell in September. Then, in the beginning of October comes the news of strong job gains in September, followed by more job gains in October, November and December. Good thing we didn’t sell at that first downturn, we tell ourselves. Meanwhile the stock market has been slipping and sliding since that first negative job report. Eventually, it will fall about 40%.

Wow, we should have taken that first signal and avoided all those losses! But if our strategy is to then buy back in when there are positive job gains reported, then we could be in and out of the market like a yo-yo in years when the economy is struggling to find direction or strength. We were looking for a more even tempered strategy.

To emphasize how the revisions in employment can mean the difference between job gains and job losses, take a look at the chart below. These are the revised figures. I have noted months where the initial monthly labor report showed positive job gains but were later revised to job losses. Some of these revisions can happen months later.

From the first reported job losses in mid 2000, more than three years passed before job gains would exceed the “replacement” level of 150,000. That is the number of jobs needed for the growth in the labor force. While many, myself included, have blamed the knucklehead politicans who enacted the Bush tax cuts in 2003, it is understandable that they were beginning to wonder if the labor market would ever turn around. Three years of job losses is a long time.

Let’s move on to the last decline. The market had already begun its decline before the first job losses were announced in early February 2008.

In this past recession, the job losses were severe but the first job increases were announced about two years after the first decrease, in early April 2010. When reviewing the historical BLS releases, this really surprised me that the 2000 – 2003 labor downturn lasted longer than this last one, though it was much less severe. By the time the first job increases had been announced in 2010, the market had already been on an upswing for a year.

In short, the headline monthly job gains don’t appear to offer a long term casual investor any particular insight or advantage. In a work force of 143 million, a hundred thousand jobs can be a slip of the pencil. But reported job gains of 150,000 or more do offer an investing hint – quit worrying about your retirement portfolio for at least another month. Go fishin’, play with the kids, hang out with friends.

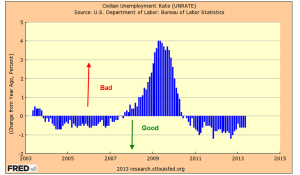

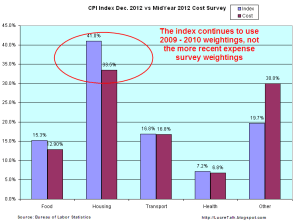

A labor indicator that seems to be more reliable is the year over year percent change in the unemployment rate, which I have discussed in earlier blogs.

Although the unemployment rate – or percentage – is derived from the count of total employment, the revisions are much smaller. Secondly, we are using a percentage gain in that percentage, further reducing swings.

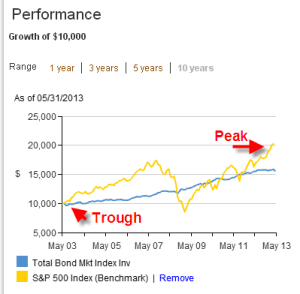

The stock market continues to post new highs in anticipation of good corporate profits in the latter part of the year. What is a bit troublesome is the number of revenue shortfalls reported by companies in the first quarter. Reducing expenses and boosting productivity can only get a company so far. Profit growth becomes harder and harder to come by without revenue growth.