June 17, 20918

by Steve Stofka

There are two types of inputs into production, human and non-human. Over a hundred years ago, Henry Ford realized that he had to invest in his human inputs as well as his equipment, land and factories. Once he started paying his employees a decent wage, they were able to buy the very cars they were producing on Ford’s assembly line.

The total return on our stock investments depends on two inputs: dividends and capital gains, which is the increase in the stock price. Both are dependent on profits. Dividends are a share of the profits that a company returns to its shareholders. Capital gains arise from the profits/savings of other investors who are willing to buy the shares we own (see end for explanation of mutual funds).

In the past three decades, a growing share of total return has come from capital gains. Because of that shift from dividend income to capital gains, market corrections are harsh and swift.

In the 1970s, stocks paid twice the dividend rate that they do today. It took an oil embargo and escalating oil prices, a continuing war in Vietnam, the impeachment of President Nixon, a long recession and growing inflation to sink the market by 50% beginning in early 1973 to the middle of 1974.

In 2000, the dividend rate or yield was a third of what it was in 1973. Total return was much more dependent on the willingness of other investors to buy stocks. In 2-1/2 years, the market lost 45% because of a lack of investor confidence in the new internet industry, a mild recession and 9-11. Dividends act as a safety net for falling stock prices and dividends were weak.

In 2008, the dividend yield was about the same as in 2000. In 1-1/2 years, the market again lost 45% of its value because of a lack of confidence brought on by a financial crisis and a long and deep recession.

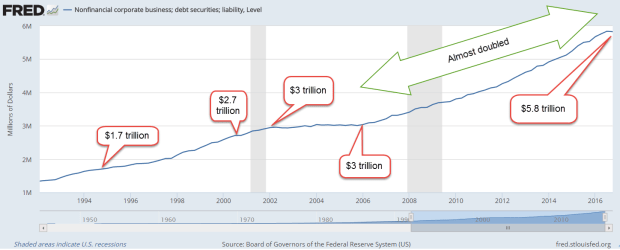

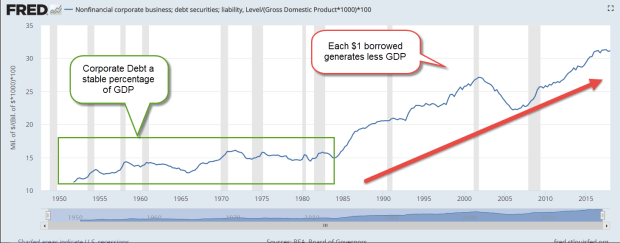

Other bedrock shifts have occurred in the past three decades. Corporate debt is an input to production. In the post-WW2 period until 1980, corporate debt as a percent of GDP was a stable 10-15%. $1 of debt generated $7 to $10 of GDP. Following the back-to-back recessions of the early 1980s until the height of the dot-com boom in 2000, that percentage almost doubled to 27%. Each $1 of corporate debt generated less than $4 of GDP.

Today $1 of corporate debt generates just $3 of GDP. Debt is a liability pool. GDP is a flow. That pool of debt is generating less flow. It is less efficient. In 1973, $1 of corporate debt generated 46 cents in profit. Now it generates just 30 cents.

To hide that inefficiency and make their stocks appealing to investors, companies have used some of that debt to buy back their own stock. This reduces the P/E ratio many investors use to gauge value, and it increases the leverage of profit flows.

Here’s a simple example to show how a stock buyback influences the P/E ratio. If a company makes a $10 profit and has 10 shares of stock outstanding, the profit per share is $1. If the company’s stock is priced at $20, then Price-Earnings (P/E) ratio is $20/$1 or 20. If that company borrows money and buys back a share of stock, then a $10 profit is divided among 9 shares for a per-share profit of $1.11. The P/E ratio has declined to 18. When the company buys stock back from existing shareholders, that often drives up the price, and thus lowers the P/E ratio further.

The P/E ratio values a company based on the flow of annual profits. A company’s Price to Book (P/B) ratio values the company based on a pool of value, the equity or liquidation value of the firm. If we divide one by the other, we get an estimate of how much profit is generated by each $1 of a company’s equity, or Return On Equity (ROE).

1982 was the worst recession since the Great Depression. Stocks were out of favor with investors and were at a 13 year low. In 1983, $8.70 of equity generated $1 of profit for companies in the SP500. Seventeen years later, at the height of the dot-com boom in 2000, companies had become more efficient at generating profits. $6 of equity generated $1 in profit. In the last quarter of 2017, companies have become less efficient. $7.30 of equity generated $1 of profit.

Let’s look at another flow ratio, one based on the flow of dividends. It’s called the dividend yield, and the current yield is 1.80, about the same as a money market account. I can put my $100 in a money market account or savings account and earn $1.80. If I need that $100 a year from now, it will still be there. I could use that same $100 and buy a fraction of a share of SPY, an ETF that represents the SP500. I could earn the same $1.80. However, if I wanted my $100 back in a year, it might be worth $120 or $50. A stock’s value can be very volatile over a short time like a year, and the current dividend rate does not compensate me for that extra risk.

Why don’t investors demand more dividends? After the early 1980s, economists at the Minneapolis Federal Reserve noted (PDF) that, on a global scale, companies’ profits grew at a faster rate than the dividends they paid to shareholders. The dividend yield of the SP500 companies fell from 6% in the early 1980s to 1% in 2000 (chart).

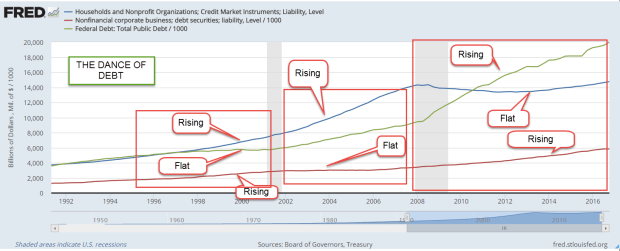

Those extra profits are counted as corporate savings. The same paper showed that global corporate savings as a percent of global GDP increased from 10% in the early 1980s to 15% this decade. Each year companies were adding on debt at a faster pace than during the post-war decades, but undistributed profits were growing even faster. The net result was an increase of 5% in the rate of corporate saving. Companies around the world were able to shift dividends from the savings accounts of shareholders to the savings of the companies themselves.

From the early 1980s to the height of the dot-com boom, stock prices increased more than ten-fold. Investors that had depended on company dividends for income in previous decades now depended on other investors to keep buying stocks and driving up the price. The source of an investor’s income shifted slightly from the pocketbooks of corporations to the pocketbooks of other investors. Investors adopted a shorter time horizon and now look to other investors to read the mood of the market.

The bottom line? If investors rely on each other for a greater part of their total return, price corrections will be dramatic.

///////////////

Notes: Price to Book (P/B) ratio was 1.5 in 1983 (article).

P/B graph since 2000

When mutual funds sell some of their holdings, they assign any capital gains earned to their fund holders. This amount appears on the mutual fund statements and the yearly 1099-DIV tax form.

A November 2017 article on share buybacks at the accounting firm DeLoitte