December 1, 2023

by Stephen Stofka

Last week I mentioned that the pandemic simulated conditions similar to a large scale war. This week’s letter explores those war-like aspects, the personal behavior and public policy choices that promoted inflation. Economists measure indicators of supply and demand to gauge the human emotion and calculation that guides decision making. Supply and demand are discernible but inseparable, a synergy of planning, emotion and reaction. Wars and global pandemics transform the routine of our daily lives into a natural experiment to help us better understand the dynamics of our daily choices.

As inflation increased in 2022, economists fell into several camps. There were those who thought the inflation was due to supply bottlenecks and that it would resolve itself. Some thought that the government had provided too much stimulus and the excess demand fueled inflation. Others thought that it was a combination of the two – both supply and demand. Some thought the Fed had waited too long before recognizing and responding to the problem of rising prices. The public sometimes gets frustrated with the arguments of prominent economists who help shape public policy.

Economists gather a lot of data and develop causal models to construct scenarios of future events. People do not respond to events like automatons. People try to anticipate what’s coming and change our behavior before anything has happened. From several blocks away I can see that the light is green but it is unlikely to be green when I get to the intersection at the speed I am going. I can either accelerate quickly or ease up in anticipation of making a full stop at the light. I am not responding to the state of the world as it is but as I predict it will be. The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889 – 1951) wrote that the future could not be inferred from the present. What if I speed up to beat the light and a driver swerves onto the road? At the same time I am making my decision to speed up, a pedestrian might think it is safe to cross the road. It is a minor tragedy in the making. What doesn’t happen is as much the reality of the moment as what does happen, Wittgenstein claimed. As economists try to predict human behavior, the subjects being studied are also trying to predict the behavior of the people and events around them.

During the pandemic, the global supply chain exhibited bottlenecks that would be more likely during a large scale war. A critical strategy during war is to disable or destroy the enemy’s supply lines. Factories, roads, railways and airports are bombed. The initial response to the pandemic was to shut down much of the global manufacturing capacity. The transportation networks were not destroyed but disrupted. For months shipping containers sat on ocean ships outside the port of Los Angeles in California. The ships could not return empty to factories in Asia and load up with more shipping containers. The conveyer belt of the global supply chain had stopped. To get critical supplies, U.S. companies hired planes to fly goods from Asian ports.

In January 2022, several economists at the New York branch of the Federal Reserve published a GSCPI composite index that estimates the price pressures in the global supply chain. You can read about their methodology here. In December 2021, the index measured a stress level that was so rare – less than four out of a million chance of occurring. In March the NY Fed estimated that global supply pressures had eased a bit but May’s report indicated worsening pressures. A month earlier the Fed had started a series of interest rate increases to curb inflation.

During a war, civilians alter their buying habits. Governments impose travel restrictions and curfews on the civilian population. Some goods are diverted to armaments. The armed forces requisitions certain foods for the soldiers fighting the war. During the pandemic, house-bound people bought household appliances and furniture, computers and entertainment devices. These are “core” goods that people buy infrequently so suppliers were likely to have a supply in stock. Stores could not restock and shelves were often bare. Where were the goods? Sitting in a container on a ship in the Pacific. By early 2021, Covid-19 vaccines were made available to seniors and others deemed vulnerable. By late 2021, restrictions on personal services like hair salons and restaurants were eased. By early 2022, a world that had gone stir crazy for two years visited restaurants, booked vacations, joined gyms and had their hair done. The household goods and appliances that stores had ordered now arrived but the public had switched their buying habits.

Many Americans had never experienced wartime restrictions and resented the heavy hand of government in their daily lives. Many states closed schools and day care facilities, leaving parents with round the clock care of their children. Some of us are content to be alone while others thrive on the company of others. As people re-emerged into normal public life, some rebelled against institutional rules of any sort. A request from a flight attendant on an airplane might incite a violent reaction from a passenger who regarded the flight attendant as representative of all institutional authority. Some passengers responded as if they were escaping from prison. They verbally attacked employees working in airlines, in restaurants and grocery stores, in hair salons and other public facing businesses. Here is a compilation of confrontations between passengers and airline employees. In the public square and on social media, we were acting as though we were at war with each other.

There are often social frictions following a war. The passage of the Prohibition amendment following World War I disrupted social relations in America. Some states and cities imposed restrictions to curtail the spread of the so-called Spanish flu (see note below). The drop in crop prices following the war put many farmers and regional banks out of business during the severe recession of 1920-21. Americans turned against other Americans, particularly minorities who enjoyed any good fortune. A prosperous Black community in Oklahoma was burned to the ground. Americans of British and northern European heritage pressed lawmakers for new immigration rules that would restrict anyone but northern Europeans from legal entry into the U.S. In 1924 Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act that imposed country quotas favoring those from northern European countries at the expense of southern Europeans and Asians.

During World War 2, Americans were at war with Japanese, Italian and German Americans in the barracks and in the public square. A 1942 musical featured a song The House I Live In to promote a camaraderie among the public. In 1945 the popular singer Frank Sinatra starred in a short movie of the same name to combat prejudicial attitudes toward minorities. In the year after the war ended, the marriage rate hit an all-time high but the divorce rate also spiked.

During the 1960s and 1970s the Vietnam War provoked social and political hostilities among Americans. The conflict erupted on public streets, on college campuses and in households where children and parents debated the ethics of the war. To a growing coalition of Americans returning vets represented the barbarous atrocities that the country’s leadership had ordered. They were treated with scorn or disregard by a public that wanted to forget the war. Many were betrayed by the bureaucratic red tape that kept many waiting for benefits that the government had promised in return for their service. See 2: 45 on this 5 minute clip from the History Channel. How does rude and antagonistic behavior affect inflation?

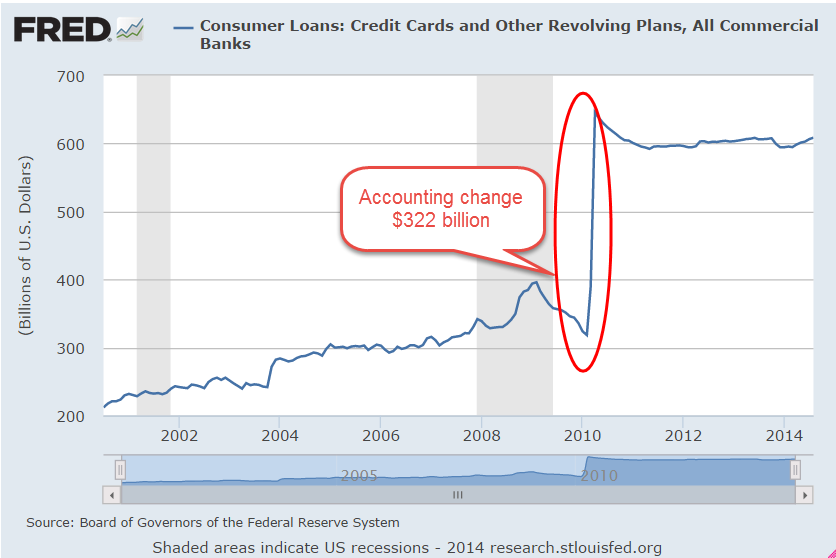

The rudeness, the lack of kindness in social relations stirs a deep sense of dissatisfaction within us. The circumstances of the pandemic aroused feelings of vulnerability and anger. The antidote to dissatisfaction is satisfaction. The antidote to powerlessness is the exercise of power. Spending money on ourselves and our family promotes a sense of satisfaction and power – just what the doctor ordered. Newly escaped from pandemic prison consumers increased their credit card balances by an average of 15% annualized in 2022 and 17% in the first half of this year. Over a ten-year period, consumers increased their credit card balances by 4% each year, slightly more than the 3.65% average of all consumer debt. As they did after WW2, Americans put the pandemic crisis behind them by us by spending.

/////////////

Photo by Shalom de León on Unsplash

Keywords: World War 1, World War 2, Vietnam War, curfews, consumer spending, credit card debt

Note on Spanish flu: The U.S., Britain and other allies suppressed news of the flu spreading among their troops. Spain did not impose wartime restrictions on publication of the news so the public first became aware of it from Spanish newspapers. Later genetic testing and historical records indicated that the origin of the world wide pandemic was an Army base in Leavenworth, Kansas.