September 27, 2015

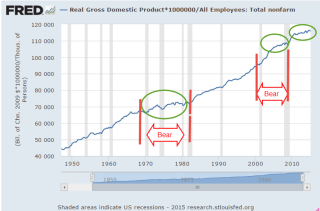

Worries about economic growth in China, in the EuroZone and in emerging markets have prompted fears of a recession in the U.S. It could happen – it will happen – at some point in the future but not in the near future. The Fed likes to use a Personal Consumption chain weighted inflation index called the PCE Price Index which more reliably captures underlying inflation trends. Preceding each recession we see the rate of economic growth fall below the annual growth rate of the PCE index, multiplied by a 1.5 factor. While GDP growth is not robust, it is far above the growth of the PCE price level.

Speaking of growth, inflation-adjusted GDP growth for the second quarter was revised upwards to a 3.9% annual rate. Consumer spending was revised higher and inventory growth – a bit worrisome, as I noted earlier – was revised lower.

The SP500 index began the year at a price level ($2068) that was just a bit above the inflation adjusted price level ($2018) of 2000 (Graph here). Oops! we’re back below that year 2000 level. A sense of pessimism since mid-August has led to an 8% decline in the broad stock index, or 6% below the price level at the beginning of 2015. A broad composite of bonds, Vanguard’s BND ETF, is also down -about 1.5% – since early 2015.

Some sectors of the market can not find a bottom. XME, a blend of mining stocks, is down 45% for the year. Brazil’s index, EWZ, is down a similar amount – about 40%. Emerging Market stocks (VWO) in general have lost about 17% this year, and are at June 2009 prices. After losing 5% of their value in the first week of September, they appeared to have found a bottom, regaining that lost 5% in the next two weeks. This past week they gave up those gains, touching the bottom again. The second time is a charm. If this market draws in buyers a second time, this might be a good time to put some long term money to work.

*******************************

Phillips – the curve, not the screwdriver

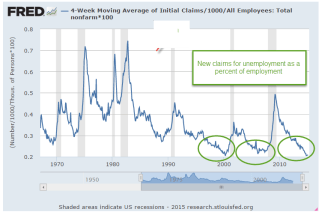

In a speech/lecture at U. of Massachusetts this week, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen voiced her desire to raise interest rates sometime this year. She included in her remarks some comments on the Phillips curve, a mainstay of economics textbooks during the past 50 years. In the 1950s Bill Phillips presented one hundred years of unemployment and inflation data in the United Kingdom and showed that there was a trade-off between unemployment and inflation. Higher inflation = lower unemployment. Lower inflation = higher unemployment. When the number of unemployed workers are low, workers can press employers for higher wages. Higher wages lead to a higher inflation rate.

As you can see in the graph above (included in the Wikipedia article on the Phillips curve), the regression estimate, the red line, shows a tenuous inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation. The standard error S of the regression estimate is a guide to the reliability of the estimate to predict future relationships in the data. The S in this regression is not shown but looks to be rather large; a lot of the data points are pretty far away from the red estimate line and so the regression model is unreliable.

Within fifteen years after the Phillips curve became an accepted tenet of economics, the stagflation of the 1970s disproved the central thesis of the Phillips curve. During that decade, there was both high inflation and high unemployment. This led economists to revise their thinking; the relationship described by the Phillips curve may have some validity in the short run but not in the long run.

For those of you who might like to go down the rabbit hole on this issue, there are several fascinating but challenging perspectives on the relationship between unemployment, the labor market, and inflation, the price level of goods in an economy. One is Jason Smith’s Information Transfer model version of the Phillips curve. Jason is a physicist by education and training who uses the tools of information theory to bring fresh insights to economic data, trends and models.

Roger Farmer (whose blog I link to in my blog links on the right hand side) has developed another perspective based on a sometimes overlooked insight in Keynes’ General Theory published in 1936. Roger is the Department Chair at UCLA’s Dept of Economics. For the general reader, I heartily recommend his book “How the Economy Works”, a small book which presents his ideas in clear, simple terms. His history of the development of central economic theories weaves a concise narrative of ideas and people that may be the best I have read.

For those of you with the background and math chops, his paper “Expectations, Employment and Prices” (also a book) contains a well-developed mathematical model of longer term economical and business cycles that find an equilibrium at various levels of unemployment. Roger undermines an idea predominant in economics and monetary policy: the so called natural rate of unemployment, or NAIRU, that guides policy decisions at the Fed and is often mentioned by Yellen and others at the Fed.