December 8th, 2013

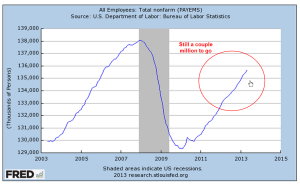

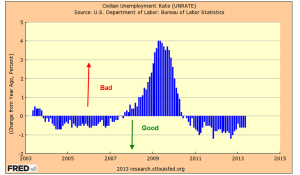

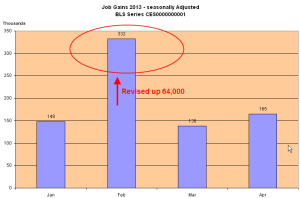

The Bureau of Labor Statistics rode down like Santy Claus on the arctic front that descended on a large part of the U.S. The monthly labor report showed a net gain of 203,000 jobs in November, below the 215,000 private job gains estimated by ADP earlier in the week, but 10% higher than consensus forecasts. Thirty eight months of consecutive monthly job growth shows that either:

1) President Obama is an American hero who has steered this country out of the worst recession – wait, let me capitalize that – the worst Recession since the Great Depression, or

2) American businesses and Republican leadership in the House have overcome the policies of the worst President in the history of the United States.

Hey, we got some Hyperbole served fresh and hot courtesy of our radio and TV!

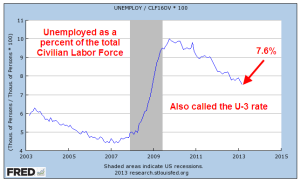

The unemployment rate dropped to 7.0% for the right reasons, i.e. more people working, rather than the wrong reasons, i.e. job seekers simply giving up. The combination of continued strong job gains and a big jump in consumer confidence caused the market to go “Wheeee!”

***********

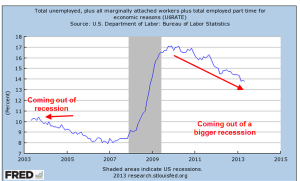

A broader measure of unemployment which includes those who want work but haven’t looked for a job in the past four weeks declined to 7.5%. This is still above the high marks of the recessions of the early 90s and 2000s.

***********

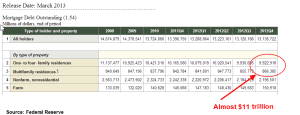

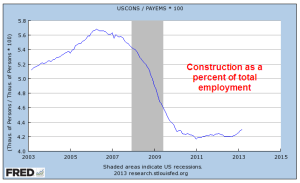

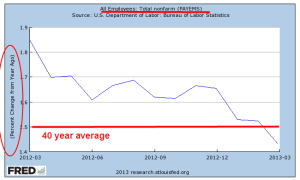

Construction employment suffered severe declines after the collapse of the housing bubble. We are concerned not only with the level of employment but the momentum of job growth as the sector heals. A slowing of momentum in 2012 probably factored into the Fed’s decision to start another round of QE in the fall of last year.

********

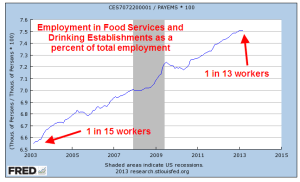

Job gains were broad, including many sectors except federal employment, which declined 7,000. Average hours worked per week rose by a tenth to 34.5 hours and average hourly pay rose a few cents to $24.15.

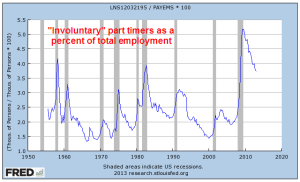

Discouraged job seekers are declining as well. The number of involuntary part time workers fell by 331,000 to 7.7 million in November. As shown in graph below, the decline is sure but slow.

***********

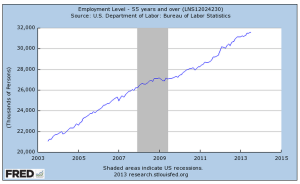

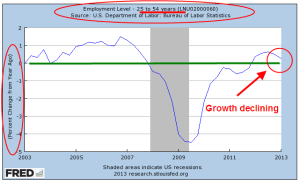

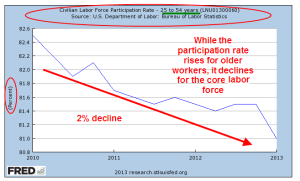

There are still some persistent trends of slow growth. Job gains in the core work force aged 25 -54 are practically non-existent.

**********

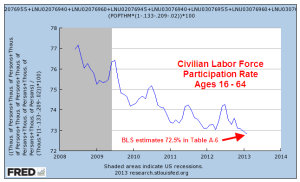

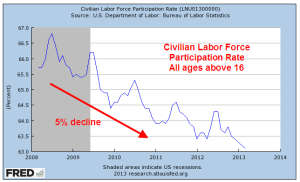

The percentage of the labor force that is working edged up after severe declines this year but the trend is down, down and more down.

*********

The number of people working as a percent of the total population has flatlined.

**********

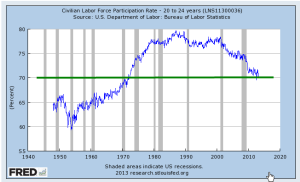

Let’s turn to two sectors, construction and manufacturing, which primarily employ men. The ratio of working men to the male population continues to decline. Look at the pattern over 60 years: a decline followed by a leveling before the next decline, and so on. Contributing to this decline is the fact that men are living longer due to more advanced medical care and a fall in cigarette smoking.

************

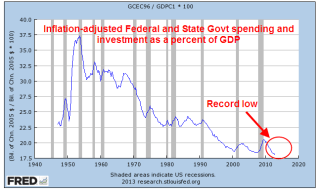

The taxes of working people have to pay for a lot of social programs and benefits that they didn’t have to pay for thirty years ago. Where will the money come from? A talk show host has an easy solution: tax the the Koch Brothers, cut farm subsidies to big corporations and defense. Taking all the income from the Kochs and cutting farm subsidies and defense by half will produce approximately $560 billion, not enough to make up for this year’s budget deficit, the lowest in 4 years. What else?

***********

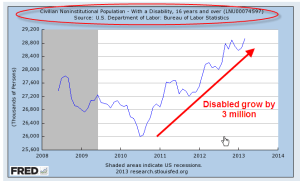

In a healing job market, those aged 16 and up who are not in the labor force as a percent of the total population continues to climb.

********************************

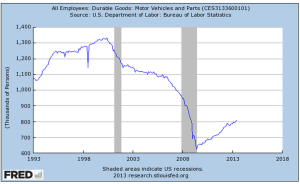

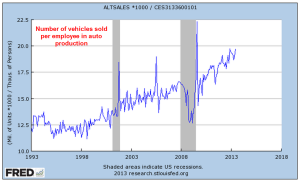

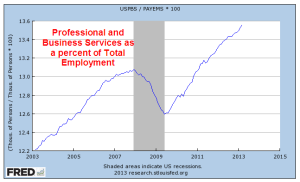

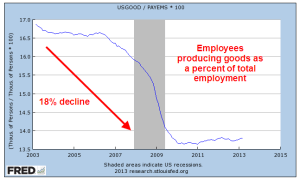

A familiar refrain is the steady decline in manufacturing employment. Recently the decline has been arrested and there is even slight growth in this sector. Although construction is regarded as a separate sector, construction is a type of manufacturing. Both employment sectors appeal to a similar type of person. Both manufacturing and construction have become more sophisticated, requiring a greater degree of specialized knowledge. Let’s look at employment trends in these two sectors and how they complement each other.

During the 90s, a rise in construction jobs helped offset moribund growth in manufacturing employment.

In 2001, China became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) , enabling many manufacturers to ship many lower skilled jobs to China. At the same time, a recession and the horrific events of 9/11 halted growth in the construction sector so that there was not any offset to the decline in manufacturing jobs.

As the economy began recovering in late 2003, the rise in construction jobs more than offset the steadily declining employment in the manufacturing sector. People losing their jobs in manufacturing could transition into the construction trades.

As the housing sector slowed, construction jobs declined and the double whammy of losses in both sectors had a devastating effect on male employment.

In the past three years, both sectors have improved.

Although the Labor Dept separates two sectors, we can get a more accurate picture of a trend by combining sectors.

*********************************

In the debate over the effectiveness of government stimulus, there is a type of straw man example proposed: what if the government were to pay people to dig holes, then pay other people to fill in the holes? Proponents of Keynesian economics and government stimulus argue that such a policy would help the economy. Employed workers would spend that money and boost the economy. Those of the Austrian school argue that it would not. Digging and filling holes has no productive value. Ultimately it is tax revenues that must pay for that unproductive work. Therefore, digging and filling holes would hurt the economy.

So, let’s take a look at unemployment insurance through a different set of glasses. Politicians and the voters like to attach the words “insurance” and “program” to all sorts of government spending. Regardless of what we call it, unemployment insurance is essentially paying people to dig and fill holes – except that the holes are imaginary. IRS regulations state that unemployment benefits are income, that they should be included in gross income just as one would include wages, salaries and many other income.

If unemployment is income, how many workers do the various unemployment programs “hire” each year? Unemployment benefits vary by state, ranging from 1/2 to 2/3 of one’s weekly wage. (Example in New Jersey) As anyone who has been on unemployment insurance can verify, it is tough to live on unemployment benefits. I used the average weekly earnings for people in private industry and multiplied that by 32 weeks to get an average pay, as though governments were hiring part time workers. I then divided unemployment benefits paid each year by this average. Note that the divisor, average pay, is higher than the median pay, so this conservatively understates the number of workers that are “hired” each year by state and federal governments.

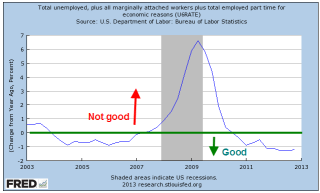

What is the effect of “hiring” these workers? I showed the adjusted total (blue) and the unadjusted total of unemployed and involuntary part time workers. The green circle in the graph below illustrates the effect that extensions of unemployment insurance had on a really large number of unemployed people.

At its worst in the second quarter of 2009, the unemployed plus those involuntary part timers totaled 24 million, almost 16% of those in the labor force. 8 million were effectively “hired” to dig imaginary holes. In the long run, what will be the net effect of paying people to dig holes and fill them? First of all, a politician can’t indulge in long run thinking. In a crisis, most politicians will sacrifice long run growth so that they can appease the voters and keep their own jobs.

In the long run, ten years for example, paying people to do nothing productive will hurt the economy. The argument is how much? Keynes himself wrote that his theory of stimulus and demand only worked when there was a short run fall in demand. At the time Keynes wrote his “General Theory,” the world economy was floundering around in a severe depression. The severe crisis of the Depression birthed a theory that divided the economists into two groups: the tinkerers and the non-tinkerers. Keynesian economists believe in tinkering, that adjusting the carburetor of the economic engine will get that baby purring. Austrian or classical economists keep asking the Keynesians to stop messing with the carburetor; that all these adjustments only make the economy worse in the long run.

***********************************

The November report from the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) showed strong to robust growth in the both the manufacturing and services sectors. As I noted this past week, I was expecting the composite CWI index of these reports that I have been tracking to follow the pattern it has shown for the past three years. Within this expansion, there is a wave like formation of surging growth followed by an easing period that has become shorter and shorter, indicating a growing consistency in growth. The peak to peak time span has decreased from 13 months, to 11 months to 7 months. The index showed a peak in September and October so the slight decline is following the pattern. IF – a big if – the pattern continues, we might expect another peak in April to May of 2014.

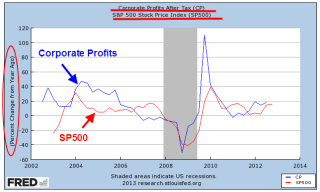

To get some context, here’s a ten year graph of the CWI vs the SP500 index.

**********************************

As the stock market makes new highs each week, some financial pundits get out of bed each morning, saddle up their horses, load up their latest book in the saddle bags and ride through TV land yelling “The crash is coming, the crash is coming.” Few people would listen to them if they shouted “Buy my book, buy my book.” They sell a lot more books yelling about the crash.

How frothy is the market? I took the log of the SP500 index since January 1980 and adjusted it for inflation using the CPI index. I then plotted out what the index would be if it grew at a steady annualized rate of 5.2%. Take 5.2%, add in 3% average inflation and 2% dividends and we get the average 10% growth of the stock market over the past 100 years. The market doesn’t look too frothy from this perspective. In fact, the financial crisis brought the market back to reality and since then, we have followed this 100 year growth rate.

Now, let’s crank up the wayback machine. It’s November 1973. Despite the signing of the Paris Peace accord and an act of Congress to end the Vietnam war, thousands of young American men are still dying in Vietnam. The Watergate hearings continue to reveal evidence that President Nixon was involved in the break in of the Democratic National Committee and the subsequent attempts to cover it up. Rip Van Winkle is disgusted. “This country is going to the dogs,” he mutters to himself. He lies down to take a nap in an alleyway of the theater district of New York City. The SP500 index is just below 100. Well, Rip doesn’t wake up for 20 years. In November 1993, he wakes up, walks out on Broadway and grabs a paper out of nearby newspaper machine. The SP500 index is 462. Rip doesn’t have a calculator but can see that the index has doubled a bit more than twice in that time. Using the rule of 72 (look it up), Rip estimates that the stock market has grown about 8% per year. Which is just about normal. But normal is what Rip left behind in 1973. “Normal” is SNAFU. So he goes back into the alleyway and goes back to sleep for another twenty years, waking up just this past month. He walks out on Broadway and reads that the index has passed 1800. “Harumph” Rip snorts. That’s two doublings in twenty years, a growth rate of a little over 7%. Rip reasons that eventually he’ll wake up, the country will have mended its ways and Rip will notice a growth rate of 9 – 10% in the market index. He goes back to sleep.

In the 40 years that Rip has been asleep, we have had three bad recessions in the 70s, 80s and 2000s, a savings and loan crisis in the 80s, an internet bubble, a housing bubble, and the mother of all financial crises. Yet the market plods along, slowing a bit, speeding up a bit. Long term investors needs to take a Rip Van Winkle perspective.

***********************************

And now, let’s hop in the wayback machine – well, a little ways back. Shocks happen. During periods when the market is relatively well behaved as it has been this year, investors get lulled into a sense of well being. From July 2006 through February 2007, the stock market rose 20%. Steadily and surely it climbed. Housing prices had already reached a peak and the growth of corporate profits was slowing. Some market watchers cautioned that fundamentals did not support market valuations. At the end of February 2007, the Chinese government announced steps to curb excessive speculation in the Shanghai stock market (CNN article). The stocks of Chinese companies tumbled almost 10%, sending shocks through markets around the world. The U.S. stock market dropped more than 5% in a week.

“Here comes the crash” was the cry from some. The crash didn’t come. Over the next six months, the market climbed 16%. Finally, continuing declines in home sales and prices, growing mortgage defaults and poor company earnings began to eat away at the market in October 2007. Remember, there is still almost a year to the big crash in September and October of 2008.

**************

Next week I’ll put on a different shade of glasses to look at inflation. Cold air, go back to the North Pole.